John Ruskin's Influence on Art and Architecture on View in London Show

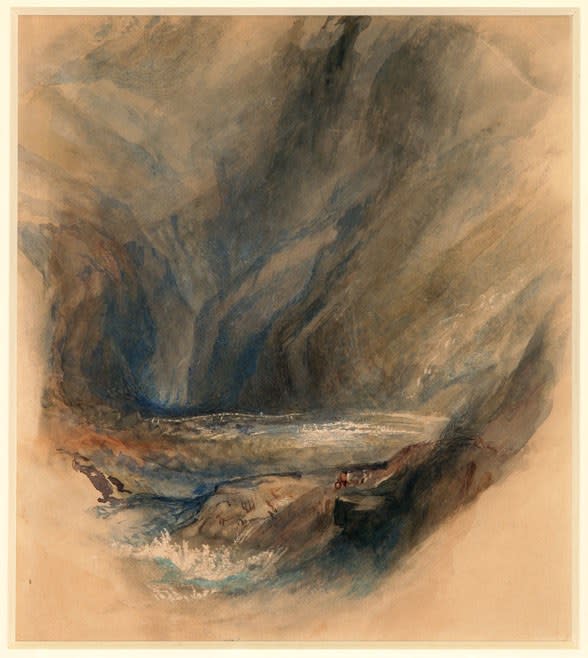

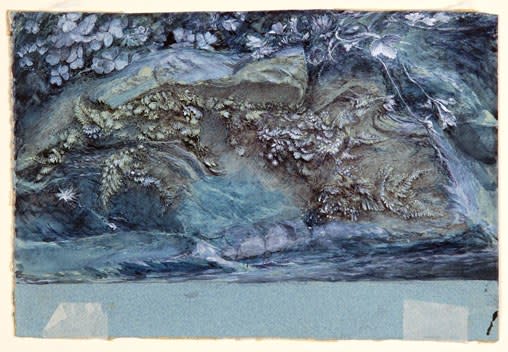

This year marks the bicentenary of the birth of art critic John Ruskin, one of the most influential thinkers of the 19th century and in many ways a role model for our own time. To celebrate the occasion, a major exhibition opens on January 26 in central London, in an extraordinary pied à terre once owned by William Waldorf Astor. Called "John Ruskin: The Power of Seeing," the show brings together a fabulously eclectic collection of pictures, prints, illustrated books, and geological specimens, as well as exquisitely detailed watercolors in Ruskin’s own hand.

Though he could hardly be called a household name today, Ruskin’s influence on art, architecture, and politics is hard to overstate. His fame spread round the world, and his fans included Tolstoy, Proust, and Mahatma Gandhi—each of whom translated his writings into their native tongues. Ruskin changed the visual taste of several generations, spearheaded the Gothic revival, inspired the Pre-Raphaelites, and laid the foundations for the Arts and Crafts movement. He rivaled Charles Dickens as a passionate campaigner for the lot of the laboring poor, while his late essay, The Storm-Cloud of the Nineteenth-Century, has good claim to be a foundational text of climate-change theory.

John Ruskin was born in Bloomsbury, London, in 1819. His father, a prosperous wine merchant, encouraged his precocious son’s passion for nature and the arts, as well as his interest in the mineral world; young John’s ambition was to be president of the Geological Society, though his devoutly Christian mother would apparently have preferred him to become the Archbishop of Canterbury. At the age of 24 he published the first volume of Modern Painters, which made his name as a cultural critic; later books only cemented his reputation, and over the course of a long and very public career, he wrote and lectured on everything from art and architecture to birds, botany, education, and social injustice.

Yet he wasn’t just an ivory-tower intellectual: Ruskin delighted in handicrafts and getting his hands dirty—on some occasions quite literally. During his tenure as Slade Professor of Fine Art at Oxford University, he organized a high-minded—if slightly farcical—attempt to repair a potholed road on the edge of the city with a group of undergraduates, rather incredibly including the young Oscar Wilde. Unfortunately, this wasn’t the first time that Ruskin invited ridicule: His marriage in 1847 proved to be a disaster, possibly because Ruskin had led such a sheltered life that the reality of sex came as a terrible shock. In 1853, his wife left him for his friend, the painter John Everett Millais, and filed for divorce the following year, alleging that Ruskin was "incurably impotent." He never referred to her again, but the scandal dogged him for decades. His occasional missteps and eccentric personality, though, shouldn’t blind us to his remarkable talents as a writer, artist, and social reformer. Ruskin was ahead of his time in many ways, and his views on art and commerce, not to mention social justice and the environment, remain all too relevant today.

The venue for the Ruskin exhibition, Two Temple Place, is both fitting and ironic. Opened in 1895 as William Waldorf Astor’s estate office, it’s the kind of ostentatiously plutocratic building that one imagines Ruskin would loathe, yet it’s of the right period and its interiors crawl with the handwrought artisanship that Ruskin so admired. Now owned by a charity and only open to the public during its annual exhibition season, Temple Place offers an intriguing insight into the crepuscular tastes of one of the titans of America’s Gilded Age. What Ruskin would have thought of Astor (and Astor of Ruskin) one can only imagine, but the combination promises to be an intriguing one.

*"John Ruskin: The Power of Seeing" runs from January 26 to April 22 at Two Temple Place, London WC2R 3BD.

More from AD PRO: Has Instagram Made Design Shows Better?

Sign up for the AD PRO newsletter for all the design news you need to know