Josephine Veasey: Star of British opera who took on the world stage

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

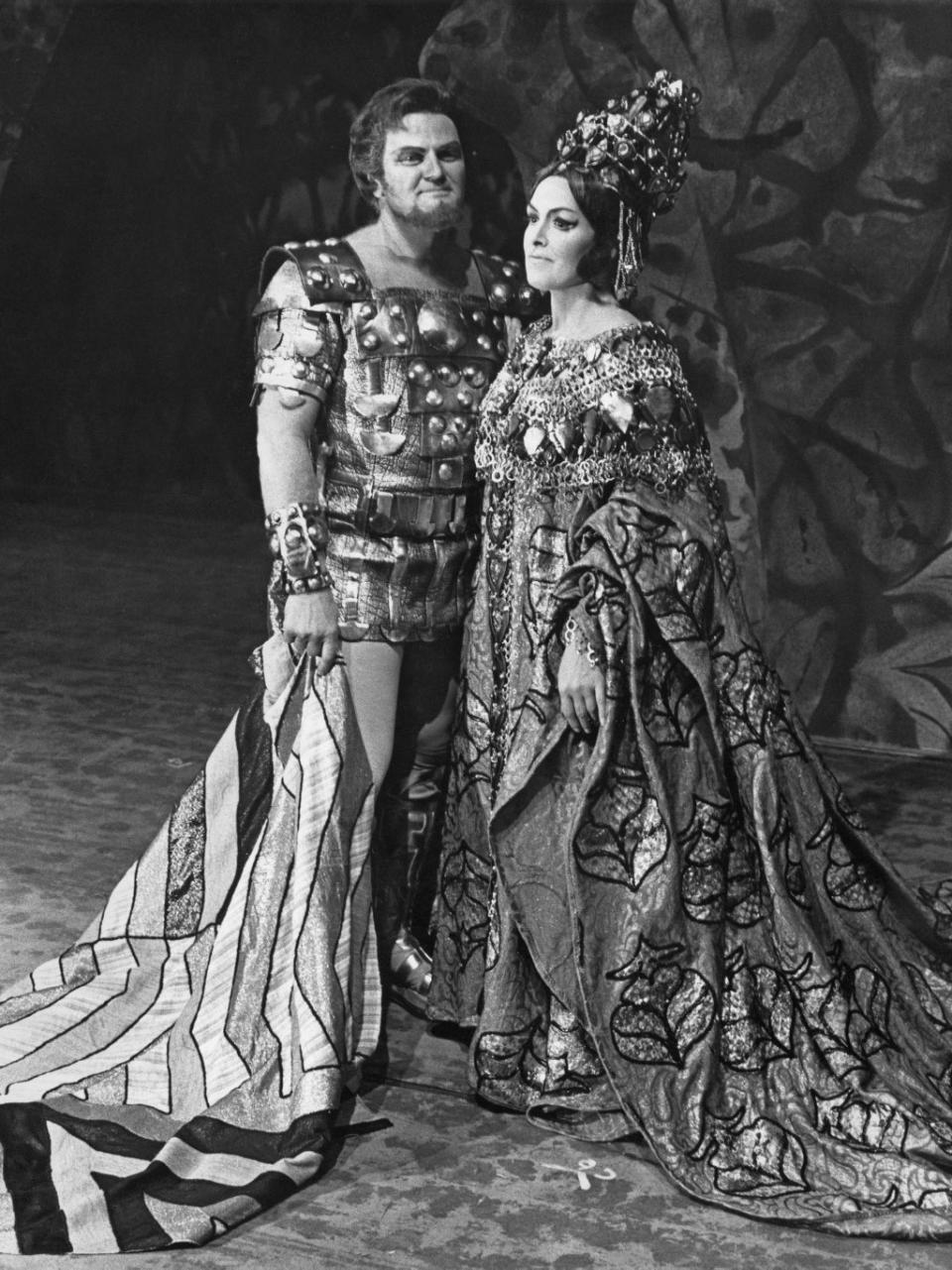

Few singers have possessed a more comprehensive and magisterial vocal technique than Josephine Veasey, who has died aged 91. Gifted with a warm, vibrant and distinctive mezzo-soprano voice that had unprecedented power and emotional appeal, she was aided too by film-star looks and an instinctive feel for characterisation – all qualities that would combine to so impress conductors, audiences, impresarios and record companies alike throughout the second half of the 20th century.

While serving as one of Covent Garden’s leading singers for almost three decades, she was also in demand at major operatic venues worldwide. In later years, her fame as a teacher and vocal coach would come to equal her reputation as a performer.

Almost from birth, Veasey had a burning ambition to become an opera singer. Playing a vital role in helping her to achieve this goal was her vocal tutor, Audrey Langford. Educated locally, Veasey first joined the Royal Opera House as an 18-year-old member of the chorus in 1949. Between then and her retirement in 1982, she would grace the Covent Garden stage on 780 occasions. She also spent a year touring Great Britain for the Arts Council with Opera For All. Unlike many of her ilk, she remained a contented but versatile mezzo who was happy to embrace all aspects of operatic repertoire.

When serving in the ranks under Karl Rankl, she was able to learn much by observing artists such as Ludwig Weber. She then progressed to small roles during the Kubelik era, with her solo debut coming in 1956. She played the Shepherd Boy in the Royal Opera’s Tannhauser, the only thing most critics remember from that staging. Her career was dramatically transformed, however, by the arrival of Georg Solti as musical director in 1961. She described him as her “musical father”, and his often outrageous charm seemed to fire her on all cylinders. He immediately cast her as Preziosilla in Verdi’s The Force of Destiny, while successfully extending her Wagnerian repertoire. With his successor, Colin Davis, it was the music of Hector Berlioz that particularly came to the fore.

Veasey had previously worked with Davis and his Chelsea Opera Group in 1963, appearing in Oxford as Cassandra in Berlioz’s opera The Fall of Troy. For many followers of the composer, she remains one of his finest interpreters. Between 1957 and 1969 her roles for Glyndebourne Festival Opera included Zulma in An Italian Girl in Algiers, Cherubino in The Marriage of Figaro, Clarice in La Pietra del Paragone, Octavia in Der Rosenkavalier and Charlotte in Werther.

After appearing in The Barber of Seville at the 1961 Edinburgh International Festival, she returned two years later to star in La Damnation de Faust, conducted by Solti. She also shone brightly at the 1980 Buxton Festival when playing Gertrude opposite Thomas Allen’s Hamlet, helping to bring Ambroise Thomas’s long-neglected work to life.

After undertaking two hugely successful tours of Israel with Solti, Veasey began inhabiting a far more international landscape. In 1972, she sang Marguerite in The Damnation of Faust in both Chicago and New York, with the maestro taking charge of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. She also worked frequently with Herbert von Karajan, singing as Fricka in his staging of The Ring which was seen in Salzburg, then at La Scala and the New York Met.

At Tanglewood, she sang in Eugene Onegin, with Seiji Ozawa conducting the Boston Symphony Orchestra. Twelve months later came her first role as Kundry at the Paris Opera, prior to moving on to Geneva. She also appeared opposite Montserrat Caballe and Jon Vickers in the famous 1974 outdoor production of Norma at the Theatre Antique d’Orange.

While revelling in the stimulus of the stage, solo song recitals held little allure for her. She did, however, become an exemplary stalwart of the English choral society tradition. Here her outlook took in everything from Handel’s Messiah with Sir Malcolm Sargent to performances of the Verdi Requiem with Leonard Bernstein.

In the concert hall, both in Britain and throughout Europe, her long-renowned and articulate advocacy of the music of Hector Berlioz helped revive interest in his sadly neglected oratorio, L’Enfance du Christ. Elgar, too, particularly The Dream of Gerontius, drew out the very best in her. No less impressive were her performances of Rossini’s Petite Messe Solennelle and his Stabat Mater. Between 1958 and 1973, she also appeared regularly as a soloist at Sir Henry Wood’s promenade concerts, bringing the 1965 season to a close in typically ebullient style.

Although she was usually associated with the grandest of classical roles, such as Gluck’s lyric tragedy Iphigenie en Tauride, often overlooked is her contribution to two world premieres of new operas by Sir Michael Tippett and Hans Werner Henze. King Priam, based on Homer’s Iliad, was composed by Tippett for an arts festival held in conjunction with the reconsecration in 1962 of the rebuilt Coventry Cathedral.

In this Veasey was cast as Hector’s wife, Andromache. First performed the evening before Benjamin Britten’s War Requiem, it was quickly reprised at Covent Garden. Fourteen years later she took on a leading role in the heavily allegorical and hugely challenging We Come to the River by Henze. Requiring a cast of 126, three separate orchestras and three performance areas, it is set in a nation ruled by an indolent and oppressive emperor, played by Veasey.

Happily, many of her performances endure both on record and on film. Alongside the now legendary Berlioz recordings with Colin Davis, the Wagnerian recreations of Herbert von Karajan, Solti’s Salome and Benjamin Britten’s Shakespearean odyssey remain two versions of the Verdi Requiem.

Notable among her early output remains the 1965 recording with John Shirley-Quirk of Debussy’s Pelleas et Melisande, all overseen by Ernest Ansermet. Shirley-Quirk is also a fine Aeneas to Veasey’s Dido, in one of two recordings she made of Henry Purcell’s outstanding miniature masterpiece. However, her input to Bellini’s Beatrice di Tenda remains undeservingly neglected. Here her sensitivity to nuance and colour allows her to take great delight in the occasional grand gesture.

Appointed a CBE in 1970, she took her leave of the operatic stage playing the part of Herodias in Covent Garden’s 1982 production of Salome. Thereafter, while teaching privately and at the Royal Academy of Music, she also helped mould the creative personalities of many of this country’s leading practitioners as a vocal consultant for the English National Opera. These included Sally Burgess, Phyllis Cannan, Adrian Clarke, Anne Evans, Felicity Palmer, Ethna Robinson, Peter Sidhom, Vivian Tierney and Alan Woodrow. Alongside an unmatched body of classic recordings, her many legacies include an approach to her art and craft that will long continue to influence all who came into contact with her.

Her marriage to opera producer Alan “Ande” Anderson, whom she wed in 1951, was dissolved in 1969. She is survived by a son and a daughter.

Josephine Veasey CBE, singer and teacher, born 10 July 1930, died 22 February 2022