CNN’s CEO is out. Can the network still get where it wants to go?

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

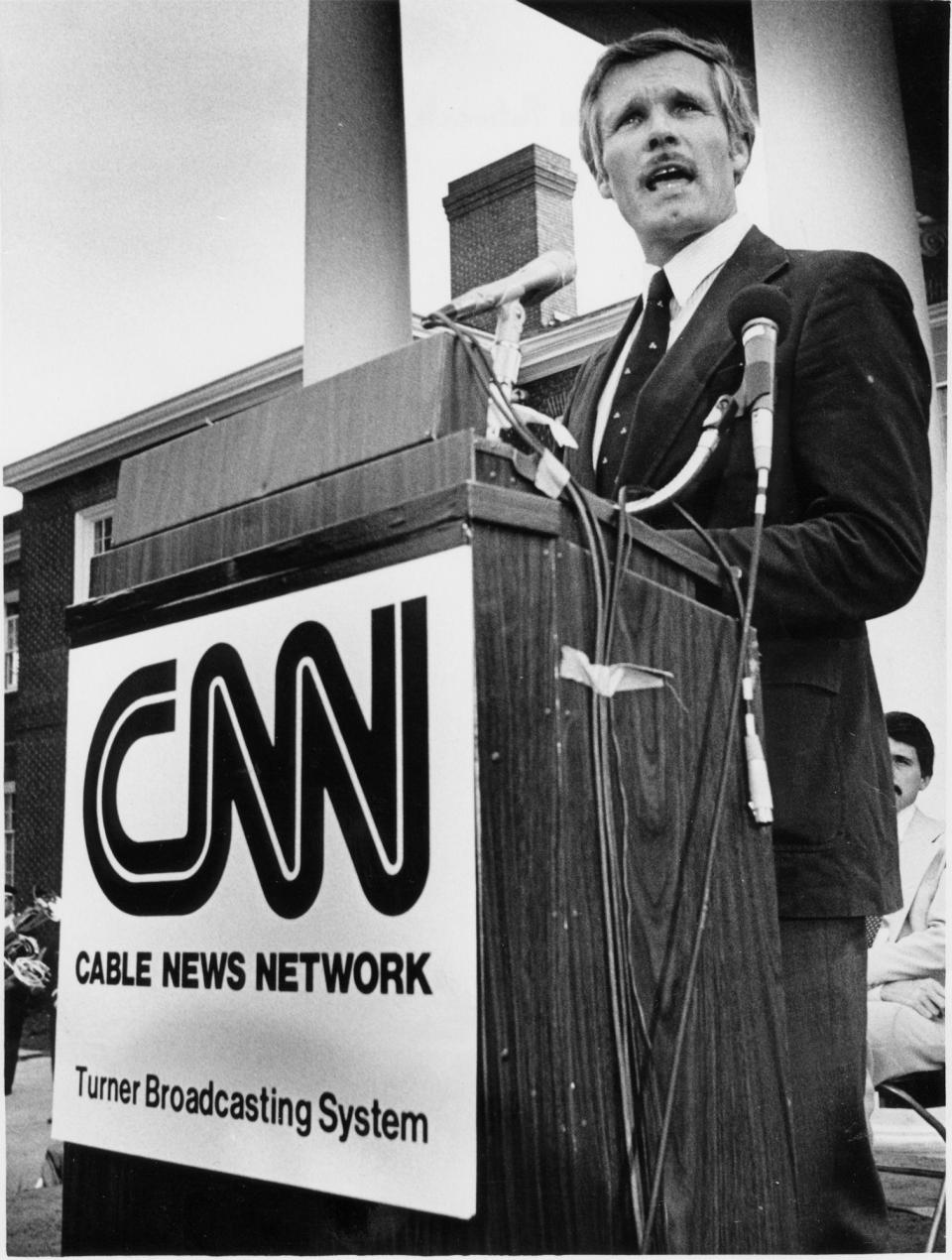

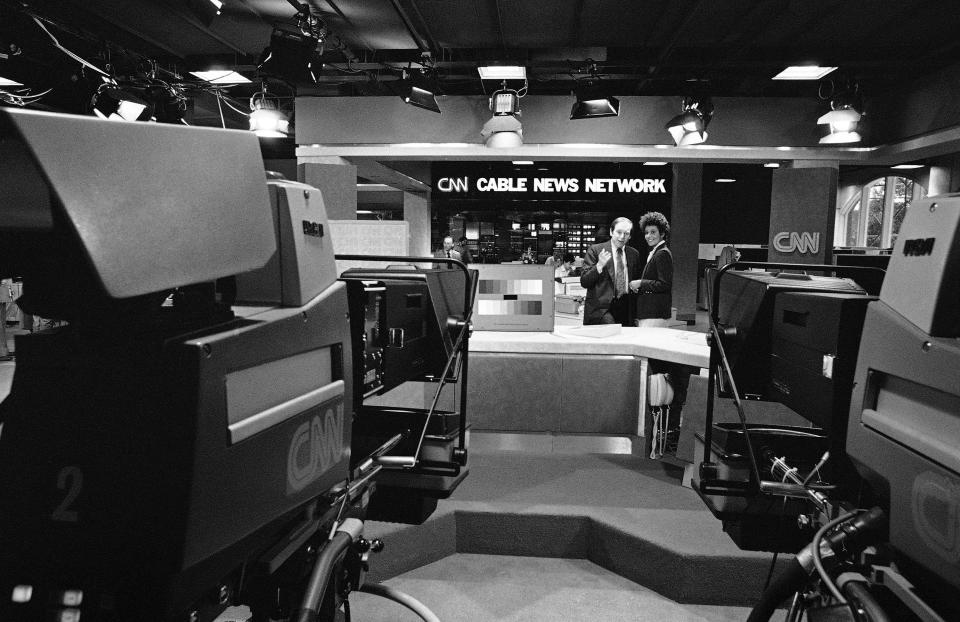

With the clock crawling toward 6 p.m. on the afternoon of June 1, 1980, Ted Turner swaggered onto a temporary stage outside a retrofitted country club in midtown Atlanta. Inside, his crew tinkered and prepped for the momentous launch of a then-revolutionary idea: A round-the-clock news network, made possible through the then-emerging technologies of satellites and cable.

Outside, Turner — nicknamed “the Mouth of the South” for his brash personality and showmanship — decided to mark the occasion, for at least a moment, with unusual solemnity. He pointed at three flags flapping in the wind nearby: One for Georgia, one for the United States, and one for the United Nations. The latter, he explained, was especially significant. “We hope that the Cable News Network, with its international coverage and greater-depth coverage, will bring both, in the country and the world, a better understanding of how people from different nations live and work together … so that we can perhaps, hopefully, bring together in brotherhood and friendship, in kindness and peace, the people of this nation and this world.”

It was a high-minded declaration from a man who once lived by the mantra “no news is good news.” He had long believed that the news was too depressing — and, even back then, that its slant was too politically liberal. But with the launch of his most ambitious project, he’d since changed his mind. News, he’d decided, could influence opinions and situations in a good way. News could be a uniting force. News could save the world. Or, at least, that’s what he said at the time.

More than 40 years later, when the now-ousted Chris Licht first visited CNN’s Atlanta headquarters shortly after becoming the company’s CEO in April 2022, that goal still echoed in the network’s mission statement. Employees should be “united by a mission to inform, engage and empower the world,” it says. But Licht’s arrival, unlike Turner’s, was not heralded with pomp and circumstance and a rendition of the national anthem. Once Donald Trump left the White House, CNN’s ratings tanked. And regardless of your political persuasion, the network had failed during the Trump presidency. For conservatives, it had leaned way too hard into the “resistance.” For progressives, it had not done enough to combat Trumpism.

The company had just been acquired by a new owner, the Warner Bros. Discovery media conglomerate, and all reports indicated the new owner had major changes in mind. Licht’s directive, then, was a course correction. “There was definitely a sense of impending doom,” says one current employee, “and this being the person who is bringing it.” The employee spoke on the condition of anonymity to avoid reprisals from her employer.

“There [was] a general sense that he’s not going to be here that long,” she added. “We [thought], he’s the guy who is going to come in, make all these big changes, and then somebody else is going to step into place for him. And most other people I’ve talked to have said something similar.” As it turned out, those people were correct. On Wednesday, Licht was fired. Warner Bros. Discovery CEO David Zaslav announced the decision on a company editorial call, wishing Licht well and taking personal responsibility for his failures. “For a number of reasons, things didn’t work out and that’s unfortunate,” Zaslav said. “It’s really unfortunate. And ultimately that’s on me.”

Licht was hired to rescue CNN from a ratings nose dive, and while the cable network no longer reaches as big an audience as it once did, it still remains highly influential.

Over 60% of American adults, per Pew Research Center, still sometimes or often turn to television for news. And when it comes to older Americans, who tend to vote at a much higher rate, TV news still has significant reach: 74% of Americans from the ages of 50 to 64 say they get at least some of their news from TV, while a whopping 85 percent of Americans over the age of 65 say they do.

And while those numbers include local news broadcasts and rabbit-ear-accessible network programs like NBC’s “Nightly News,” it’s cable news that holds an outsized influence over agenda setting — the medium that’s more likely to tell viewers what to think, rather than just what happened today, and therefore wields enormous power over how Americans perceive the world, their politics and their democracy. With that kind of potential to shape the nation’s future, Licht’s CNN wanted to rebrand itself as what it once was: a reliable source of accurate information and reasonable, thoughtful analysis.

And the approach he took in the beginning did beginning resemble the company’s original architects’ vision as a place where news is the star. “This role as the One True Reliable Source is, I think, the one that CNN wants to regain,” Slate correspondent Justin Peters wrote last September. But is it even possible to be the “one true reliable source” in 2023 and beyond?

And even if the answer is yes, does anybody want objective, down-the-middle news anymore?

CNN’s beginnings under Ted Turner

A common refrain among one segment of CNN critics is that the network should stick to “just the facts,” harkening back to an idyllic time when anchors read the news and left the hot takes and squabbling to the viewers. Among such critics is John Malone, a billionaire media mogul and influential shareholder in CNN’s new parent company. “I would like to see CNN evolve back to the kind of journalism that it started with,” he told CNBC in November 2021, “and actually have journalists, which would be unique and refreshing.” To be sure, the balance between hard news and opinion has shifted over the years, at every TV network. But did this simpler time ever really exist?

Certainly, trust in news media used to be much higher than it is today — despite what Ted Turner saw as a liberal bias among network anchors and the depressing nature of many news stories. His first cable success, an outfit called Channel 17 that eventually became TBS Superstation, even sought to counterprogram the evening news with comfort viewing, like reruns of “Star Trek” and “Hogan’s Heroes.”

Despite his eventual conversion, CNN didn’t come about because Turner changed his mind about news and its importance. It was — and, importantly, remains — a profitable business opportunity. Turner wasn’t even the one who came up with the idea; one of his deputies did. “It wasn’t Ted Turner’s vision to have news be the star. It was the people he hired. Ted Turner didn’t care,” Lisa Napoli, author of the book “Up All Night: Ted Turner, CNN, and the Birth of 24-Hour News,” told me. “All he cared about was this interesting confluence of technology in cable television and satellites, and he wanted to find a way to deploy it. And news just seemed like the easiest thing for him to wrangle.”

Turner was happy to support such a vision, but it quickly became apparent that the idea of having an entire day to gather and deliver the news, rather than a half-hour at suppertime, did not necessarily translate to more nuanced and substantive coverage. Some observers, according to Napoli’s account, dismissed CNN’s early approach as “junk-food news.” The reputation grew following the attempted assassination of President Ronald Reagan in 1981, when CNN had to fill hour after hour with a huge story — despite very little new information. As Napoli writes, from that day forward, “news would mean following an endless shower of unfolding details, right before your very eyes. News, in other words, had become sports.”

CNN’s influence continued to grow in the decades following its launch, most memorably in 1991 when the network provided live, expansive, on-the-ground coverage as bombs fell on Baghdad to begin the Gulf War. “That was compelling to watch,” New York University journalism professor and media critic Jay Rosen told me. “It didn’t necessarily give you good information about what the entire war effort was … but it became a regular part of the media and the news system.” From there, Rosen says, CNN’s identity as a not-left, not-right, “we’re just the news” network started to develop. Despite occasional controversies over bias and fairness, that was, at the very least, the brand the company was courting; as recently as the 2012 presidential election, CNN advertised its coverage under the slogan, “The only side we choose is yours.”

The central question facing CNN today is whether it’s possible to “evolve back” within a very new and different media environment. “The U.S. is a divided government. We need to hear both voices. That’s what you see,” said the man who hired Licht, Warner Bros. Discovery CEO David Zaslav, in a May interview with CNBC. “When we do politics, we need to represent both sides. I think it’s important for America.”

That sure sounds a lot like how Turner saw the company when it was founded; as a forum to promote a reasonable exchange of competing ideas; as a place where we could listen to each other and find commonalities and understanding through rigorous, fact-based reporting. But while Zaslav echoed Turner’s original vision of a “both sides” view of the political landscape, such a view doesn’t take the current moment into adequate account — nor does it promise profit. When the CNBC interviewer asked Zaslav whether people would actually watch CNN’s new approach, he was optimistic — but he also didn’t offer any concrete reason to believe him. “We’ve got a great political season coming,” he said. “This is a new CNN.”

‘The moment Trump came down the escalator’

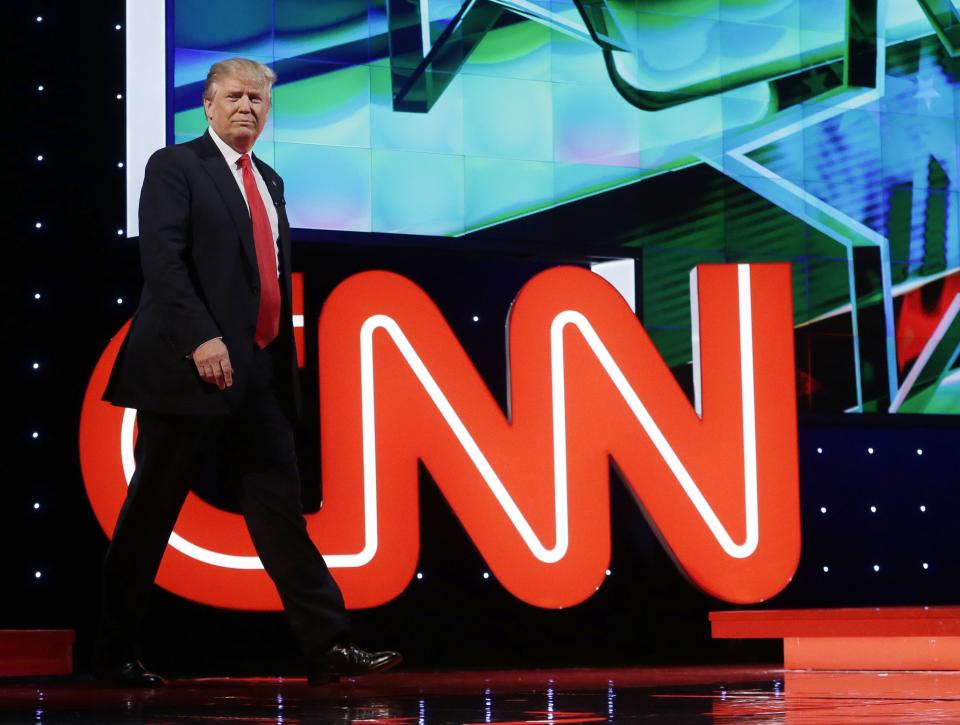

CNN’s current identity crisis traces back to 2013, the year Jeff Zucker became president. His background was in both news and entertainment. He began his career first as a producer on the “Today Show,” then as president of NBC entertainment, and, in 2007, was appointed president and CEO of NBC Universal. When he came to CNN, he brought that entertainment bent with him. “When he arrived — and people forget this — he said CNN is not about politics,” says one ex-CNN staffer. He started a sports show hosted by then-ESPN reporter Rachel Nichols. Anthony Bourdain’s hit show, “Parts Unknown,” began during Zucker’s first year. “The reality was Jeff’s attempts to put on sports and lifestyle and entertainment, it fell apart,” says the ex-employee. “That fell apart the moment Trump came down the escalator.”

That was true not only at CNN, but across most of the mainstream press. When Trump announced his bid for the GOP nomination in 2015 he challenged, at a level no politician ever had, two traditional assumptions of political reporting: cordiality and (at least some semblance of) a good-faith give-and-take. No sitting president had vilified the press since the advent of TV news to the extent Trump did. CNN in particular constantly found itself in his “fake news” crosshairs, culminating in the revocation of a reporter’s press credential in November 2018 after a feisty exchange during a White House briefing. “(Some people) describe what happened (at CNN) when Trump showed up as shifting to the left or becoming more liberal. And I don’t buy that at all,” Rosen says. “What happened is, the president of the United States was an incredible liar. … So what you have is the most powerful source of misinformation in the culture is also the elected president of the United States. That’s a crisis for news organizations.”

Conservative observers — who’ve long been more skeptical of mainstream media than liberals — could argue that what Trump really provided CNN was a lucrative excuse to shed the albatros of “objectivity” once and for all. It’s certainly true that the network heaped (often negative) coverage of Trump onto its airwaves far more than past presidents; according to the Stanford Cable TV News Analyzer, CNN devoted well over twice as much airtime to discussing Trump during his four-year term as it did to former President Barack Obama during his second term. The most recently available data shows that CNN has so far covered President Joe Biden about 30% less than Trump. The disproportionate coverage could, in part, be the result of CNN pundits feeling like they’d suddenly been granted a license to bludgeon a despised politician. But even Trump’s biggest fans largely admit that he really is something different. Indeed, that was part of his appeal. And a mainstream cable network’s coverage of him, the thinking appears to have been, demanded difference, too.

CNN first responded to the unprecedented situation by hiring pro-Trump pundits to basically fight with the rest of their pundits on air. “And that can be exciting in a way. It can be satisfying to see someone put down on live television,” Rosen says. “But it’s a very weird solution because one person you’re paying is kind of making it harder for another person you’re paying to speak the truth.” CNN, according to one study, was found to have booked fewer conservative-aligned speakers as the Trump presidency unfolded, while Fox News doubled down. Whether that could really be called “moving left,” it at least exacerbated polarization in a very noticeable way.

Josh McCrain, a University of Utah political science professor who has documented this polarization, said he can’t speak with certainty about CNN’s motivations, but he suspects its apparent “move to the left” had to do with courting an audience. “One thing that we know very reliably about people’s media diet is that they want to consume media that basically confirms their prior beliefs. People do not choose to consume media, especially about politics, that is outside of things that they don’t already agree with,” he says. “That’s sort of what Fox News figured out relatively early on: If they appeal to one side of the political spectrum, then that’s a pretty viable business model.” Zucker was a master at juicing ratings, and given his entertainment background, such a model would seem perfectly acceptable, at least business-wise, to direct CNN’s future.

But as early as 2016, Rosen had already observed how Trump’s candidacy — let alone his eventual presidency — could “fry the circuits” of mainstream American media. His observation rested on the idea that journalists generally assume politics are a question of “warring philosophies.” They assume both political parties are symmetrical — two competing teams with competing ideas, but grounded in a mutual level of respect, sincerity and commitment to basic facts. Think John McCain shutting down a supporter who called his then-political rival, Barack Obama, an “Arab” during a town hall in 2008. And that’s the rule book mainstream journalists were playing by when Trump was elected. So, “Imagine what happens,” Rosen wrote, “when over time the base of one party, far more than the base of the other, begins to treat the press as a hostile actor.” Imagine what happens, he continued, if a major political leader is a hurricane of misinformation and conspiracy; if he denies the legitimacy of any outcome that doesn’t declare him the winner; if he refuses to engage with basic, verifiable facts.

Rosen’s advice to news organizations facing such a storm is to favor a “pro-democracy agenda.” Which, at the current moment, sounds a lot like saying a pro-Democrats agenda, but Rosen insists that isn’t the case. Republicans are perfectly capable of being pro-democracy, and Democrats are perfectly capable of being anti-democracy. But the movement Trump started, he argues, simply cannot be given the same good-faith platform media organizations have traditionally given politicians. The question then becomes, “Can you cover politics in a way that feels like it’s in the middle?” says one former CNN staffer. “I don’t even know how you’d measure that.”

Zucker resigned in February 2022 after failing to disclose a romantic relationship with a colleague — which one ex-employee described as a very well-known secret around the office. She viewed the rationale for his ousting as a scapegoat to bring in someone with a new vision for the company. And though this ex-employee didn’t much care for how Zucker handled the network’s coverage of the Trump presidency, she notes that he courted plenty of loyalty. First and foremost because of his unprecedented rating success — a chance to claim the moral high ground while also stacking the company coffers. “During the Trump era, I got paid more on my bonuses than I had ever been paid,” the ex-employee says. She also liked that Zucker took a uniquely personal role in directing the company’s day-to-day operations. “He’d come sit in your meetings, he’d come sit by your desk and talk to you. Everybody felt like they knew him,” she says. “And Chris (Licht) was not like that.”

Chris Licht’s tenure begins

Licht began his tenure with a major trim. In late April, not even two months after he’d taken the job, he announced that the company’s $100 million streaming service, CNN Plus, would be discontinued after barely three weeks of operation. Then came a string of high profile sackings. In August, the company fired longtime media critic and host of “Reliable Sources,” Brian Stelter. In September, the ax found White House correspondent John Harwood. In December, a massive round of layoffs snagged political commentator Chris Cillizza, business reporter Alison Kosik and anchor Martin Savidge, among others. And none of that accounts for multiple employees who left the company amid the new direction, like investigations editor Pervaiz Shallwani. Licht also moved night time anchor Don Lemon from his night time slot to a revamped morning show (before eventually firing him).

Major changes were afoot. But, to hear Licht tell it, the common understanding of his vision — one where CNN is a “centrist,” vanilla network to balance out Fox News and MSNBC — was not correct. “You have to be compelling. You have to have edge. In many cases you take a side. Sometimes you just point out uncomfortable questions,” he said in a November interview with the Financial Times. “But either way you don’t see it through a lens of left or right.” In other words, his philosophy seems to have been when Trump makes news, report on it. When he lies, call him out on it — and treat Joe Biden the same way.

On the surface, it sounded refreshing compared to what CNN’s programming often looked like during the Trump presidency. “I’m a big fan of … independent reporting and telling people what’s going on and doing it in as thoughtful and sensible a way as you possibly can,” says Bill Grueskin, a professor at the Columbia Journalism School. In his view, CNN hasn’t done a ton of that of late. “It’s usually people sitting around the table. Sometimes they’re bringing in the reporters from Ukraine, or Washington, or Boise, Idaho, or something. But a lot of it is commentators on both sides kind of providing their special sauce of the day.”

But “telling people what’s going on” isn’t as simple a task as it once was. CNN and Fox News told their audiences very different things about “what was going on” in the aftermath of Jan. 6. And the fear among media observers is that, in the name of appearing neutral, CNN will apply criticism to both parties on a basis of equal time rather than equal merit.

And then there’s the phenomenon of Trump, who has demonstrated a Svengali-like genius to attract media attention. If the thinking is to talk about Trump only when he “makes news,” he’ll make sure he’s the focus 24/7. Which raises the question of how much will actually change. “The way I view (Licht’s) strategy is to say (CNN’s) changed more than (it’s) actually changed,” one former staffer told me in May. In other words, to create a veneer of neutrality and impartiality, while still holding Trump accountable for his lies. “The volume is three or four decibels lower than it used to be,” the ex-staffer added. “But it’s still the same song.”

Underneath the high-minded overtures about journalism and truth, the question of the new CNN’s profitability still simmers. Ratings remain terrible in comparison to rivals, having dropped to a 10-year low in February to a little more than half a million viewers in prime time. Which is why it’s worth remembering that despite the clear vision of the company’s new leadership, their approach is still a gamble. “There’s not a huge amount of untapped demand for, quote unquote, ‘centrist reporting,’” McCrain says. “I’m not convinced that there really is a business model for whatever the middle-of-the-road option is.” Especially when the internet provides so many options for content — even the most “centrist” person in the world can find an outlet that suits them more than an aggressively nonpartisan cable news channel. “CNN isn’t going to regain its pre-internet stature, because that stature was largely a function of the era’s structural limitations,” Peters, the Slate contributor, writes. “People have more options now, and the big names in news and opinion no longer serve the same unifying roles that they once did.”

Yet in service of that goal, the faces on the network have changed. Licht made a much-publicized trip to Capitol Hill last June to invite Democrats and Republicans alike on air, but one of his major prerogatives was to convince Republicans that they wouldn’t be attacked — at least not outside the bounds of the particular policy issue they’d agreed to discuss. Come to CNN, he told them, to stress test your messages to a more mainstream audience than you’ll find on Fox or other conservative outlets. No more hosts seeking viral moments for viral moments’ sake; just thoughtful policy questions.

Soon, though, the new CNN showed itself to be something else entirely.

Fallout from the Trump town hall

Today’s CNN headquarters in downtown Atlanta no longer showcases the United Nations flag that marked the original. Instead, inside the sunlit atrium in the center of the building, above a display of flags from around the world, is a giant American flag. Which seems appropriate enough a metaphor for how Turner’s Cable News Network has changed. The company that claimed at its inaugural event in 1980 that it could usher in something very close to world peace — an “It’s a Small World” ride but with chyrons — is now left trying to retain relevance in its home country.

America, too, is a very different place in 2023. When it came to programming, Licht opted to bide his time. He fired people and helped revamp the network’s morning show — but he waited more than a year to make a splash hire or fill a primetime slot or initiate a defining event. It finally arrived in May, when CNN announced it would air a live, hour-long town hall event with Trump.

Related

The event would take place in New Hampshire, a full nine months before the state’s primary, supposedly to help undecided voters and the American public in general hear from the GOP’s undisputed presidential favorite. Many observers — Rosen and Grueskin among them — warned that it would be impossible to contain Trump; that giving him such a prominent platform would misinform its audience more than provide any useful new information. But CNN was unwavering. This was exactly the sort of thing the network wanted. “President Trump is the Republican frontrunner, and our job despite his unique circumstances is to do what we do best,” a CNN public relations rep said in defense of the network’s decision. “Ask tough questions, follow up, and hold him accountable to give voters the information they need to sort through their choices.”

The event, held on May 10 — in front of a crowd stacked with Trump supporters and undecided Republicans who planned to vote in the primary — came only one day after Trump was found liable for sexual abuse and defamation of E. Jean Carroll.

“We’re here,” host Kaitlan Collins began, “to give voters the answers they deserve.”

She then asked Trump why Americans should elect him once more when he still hadn’t acknowledged the 2020 election results. “Unless you’re a very stupid person, you see what happened (in that election),” he answered. “That was a rigged election.” He talked about stuffed ballot boxes. He talked about how Mike Pence should have helped overturn the results — to raucous applause. He got a round of giggles for calling Nancy Pelosi “Crazy Nancy,” as well as for calling Carroll a “whack job.” Collins herself got laughed at when Trump took issue with her attempts to refute his lies and called her “a nasty person.”

One moment in particular was perfectly illustrative of Trump’s brilliance as a master media manipulator. Of all things, it occurred when Collins asked about raising the debt ceiling. “You once said using the debt ceiling as a negotiating wedge could not happen,” she said.

“Sure,” Trump answered, “that’s when I was president.”

“So why is it different now?” Collins asked.

“Because now I’m not president.”

When asked whether he would accept the results of the 2024 election, he said he would only “if I think it’s an honest election.” Which, as we learned in 2020, means an election where he wins.

The next day, one CNN journalist told Vanity Fair, “The mood (at the company) is absolutely the lowest it’s been in the Licht tenure, and that’s saying a lot.” And despite CNN’s own media critic observing that “it’s hard to see how America was served by (that) spectacle of lies,” Licht felt vindicated. At least that’s what he said. In a morning meeting with disgruntled employees, he expressed his understanding of the event as an unqualified success. “America was served very well by what we did last night,” he told them. He also defended putting Trump on stage with an overwhelmingly supportive audience, because the audience represented “a large swath of America” that was overlooked in 2016.

Which could be true, though it’s hard to argue that particular “swath” of America is still overlooked at this point. Trump-haters and Trump-lovers alike all know exactly who he is. So what did CNN’s town hall accomplish? The Atlantic’s Tim Alberta, who spent a year conducting on-the-record interviews with Licht and dozens of CNN employees for a 15,000-word piece published in early June, wrote that while Licht expressed outward confidence about the outcome, even he was transparently worried about what he’d unleashed. Self-doubt had infected the once-confident CEO, Alberta reported. That and other revelations elicited a firestorm in the media world, with more calls for Licht’s resignation.

Soon, Zaslav elevated a trusted lieutenant, longtime Discovery executive David Leavy, to be CNN’s new chief operating officer and Licht apologized to his staff for his failures, vowing to “fight like hell to win back their trust.” It wasn’t enough. On June 7, five days after the Atlantic story dropped, Licht was fired.

The network’s future remains uncertain. Licht had, in the eyes of many observers, squandered whatever opportunity he had to build something transformative. At a time when cable news’ relevance is tied to the drama, the controversy, the spectacle; at a time when America is so polarized that we can’t agree on a shared set of basic facts or see our fellow citizens as much more than political labels, CNN should be uniquely positioned to bridge that divide. Yet nearly every move the network has made in the past year suggests a different approach — one with an uncertain future, and an already-undeniable impact.

Long before the town hall, before his advisors expressed their giddiness over the outcome, Trump took to Truth Social to declare his enthusiasm for the event and the new approach. “Going into the heart of Enemy territory,” he wrote, “but maybe the Enemy is changing?”

This story will appear in the July/August issue of Deseret Magazine. Learn more about how to subscribe.