Judge dismisses lawsuit against State College, police involving death of Osaze Osagie

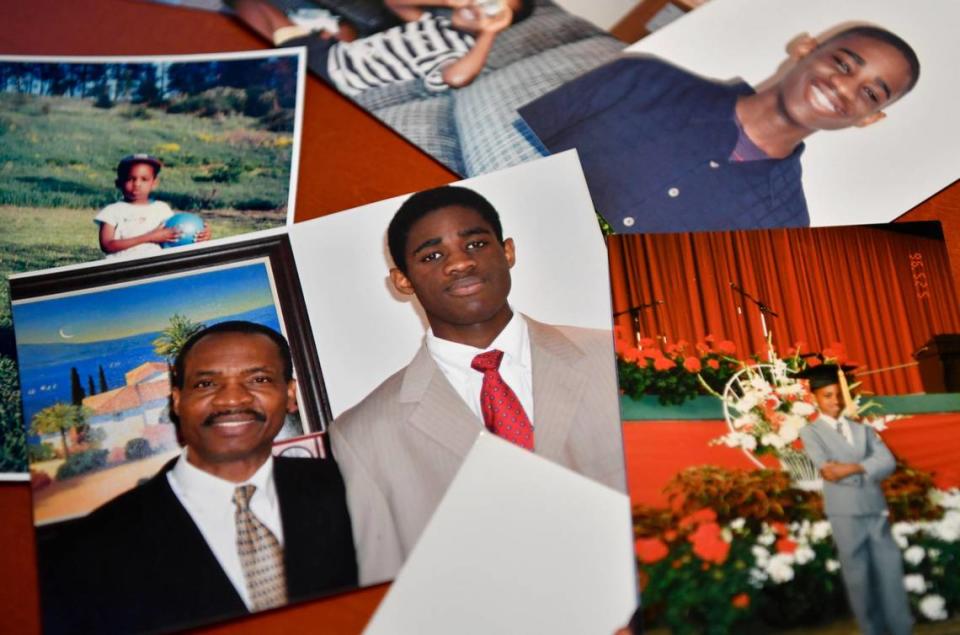

A federal judge recently dismissed a lawsuit filed by the father of Osaze Osagie, a Black State College man who was fatally shot by a police officer in 2019 when trying to serve a mental health arrest warrant.

U.S. Middle District Judge Matthew W. Brann issued the summary judgment Monday, three years after the lawsuit was initially filed. In a 46-page memorandum opinion, Brann wrote that local police officers could not be held liable for something they are not — and they were not mental health experts. Remaining defendants in the case included State College Borough and four police officers in M. Jordan Pieniazek, Christopher Hill, Keith Robb and Christian Fishel.

“Though the Court empathizes with the loss suffered by the Osagie family, that does not entitle them to relief,” Brann wrote. “The State College Police Department is, as the name suggests, a department of police officers, not mental health professionals.”

Osaze’s mother and father were seeking unspecified monetary damages for what they previously described as the police department’s “years of systematic failings” when it came to protecting the rights of individuals with mental health disabilities.

When asked for comment, a Borough spokesperson said they were still reviewing the ruling. The legal team who represents the Osagie family — Andrew Shubin, Kathleen Yurchak and Andrew Celli — issued a written statement Tuesday.

“While the family is devastated by the Court’s decision, they understood at the beginning of this process that Courts are reluctant to impose civil liability on police departments even when their encounters with the mentally ill, those in desperate need of treatment, are fatal,” the statement said. “In its memorandum, the Court wrote that it was beyond its ‘purview’ to determine the solution for how to best fill the ‘gaps through which individuals such as Osagie fall and law enforcement’s role in that solution ...’

“Although the family hasn’t decided whether to file an appeal, they will continue to honor their son by bringing light to the manner in which law enforcement interacts with the mentally ill; they believe these encounters, done responsibly, should result in compassionate and empathic treatment rather than the death of a loved one.”

According to police reports and court documents, the events of the case began when Osaze — a 29-year-old autistic man with schizophrenia and bipolar affective disorder — was acting “erratically” in the two weeks leading up to his death in March 2019. Longtime friends described him as a “gentle giant,” a caring churchgoer who would volunteer to do neighbors’ yard work, but he was different when he was off his medication.

And Osaze’s father worried he had discontinued his meds, especially after a text message from his son that read, in part, “Any poor soul whose life I take today, if any poor soul at all, may God forgive his sins if he has any.”

On March 20, 2019, three officers — Pieniazek, Hill and Robb — were sent to Osaze’s apartment along Old Boalsburg Road to involuntary transport him to the hospital. According to police, Osaze instead ran toward the officers inside a narrow hallway with a steak knife in his right hand. A Taser was ineffective, and he was shot three times, once in the shoulder and twice in the back. The department did not have body cameras at that time.

The lawsuit, filed in November 2020, accused officers and the borough of excessive force, assault and battery, failure to supervise, among other counts. Brann ruled the officers were entitled to qualified immunity, writing that the law affords officers “the breathing room to make reasonable but mistaken judgments” when it comes to individuals with mental health issues.

Police officers did not act unreasonably, Brann added, and they did not have time to de-escalate the situation.

“More fundamentally, the state of the law regarding how law enforcement should approach mentally ill individuals ‘remains relatively primitive,’” Brann wrote. “Though today’s police forces bear little resemblance to those of the 1800s, dealing with serious criminals has long been among the core responsibilities delegated to law enforcement.

“In contrast, the increasing reliance on police ‘to respond to crises arising from a mental illness’ is a relatively recent phenomenon. Thus, consensus regarding how law enforcement should respond to such situations remains elusive.”

Brann rejected a number of arguments, such as concerns over a policy-required crisis worker not being on scene for Osaze. Although State College Police Department’s policy called for such a crisis worker in those situations, Centre County Mental Health Services has never sent out a crisis worker to help serve a mental health warrant, at least not for decades.

State College Police Chief John Gardner acknowledged during a deposition, cited in court documents, that the policy has long not been followed. The county agency — which was not part of the lawsuit — has said it’s not their responsibility.

“I know what this policy says, but I also know in practicality and reality what we’re left with,” Gardner said. “I cannot dictate to another agency what they should or shouldn’t do. I can only voice the concerns I have and I’ve done that over the years.”

Osaze’s death, the first fatal shooting in the police department’s history, rocked the community more than a year before George Floyd was murdered by a Minneapolis police officer, which put conversations on race at the forefront of the nation’s consciousness. Community groups marched downtown for “Justice for Osaze,” a group formed shortly after Osaze’s death and was named after the date he died (3/20 Coalition), and meetings and prayers have continued.

State College Borough adopted a number of police reforms in the wake of Osaze and Floyd. All officers are now outfitted with body cameras, the police department has pursued a social worker program, Borough Council created a Community Oversight Board, a Mental Health Task Force was established, etc.

“Much more needs to be done,” said the statement from the Osagies’ legal team, “but the family takes comfort in the love and support of the community and the fact that their response to this son’s death played a role in achieving some measure of change.”

CDT reporter Bret Pallotto contributed to this story