A judge fled the Taliban in Afghanistan. Now he waits to be reunited with his family

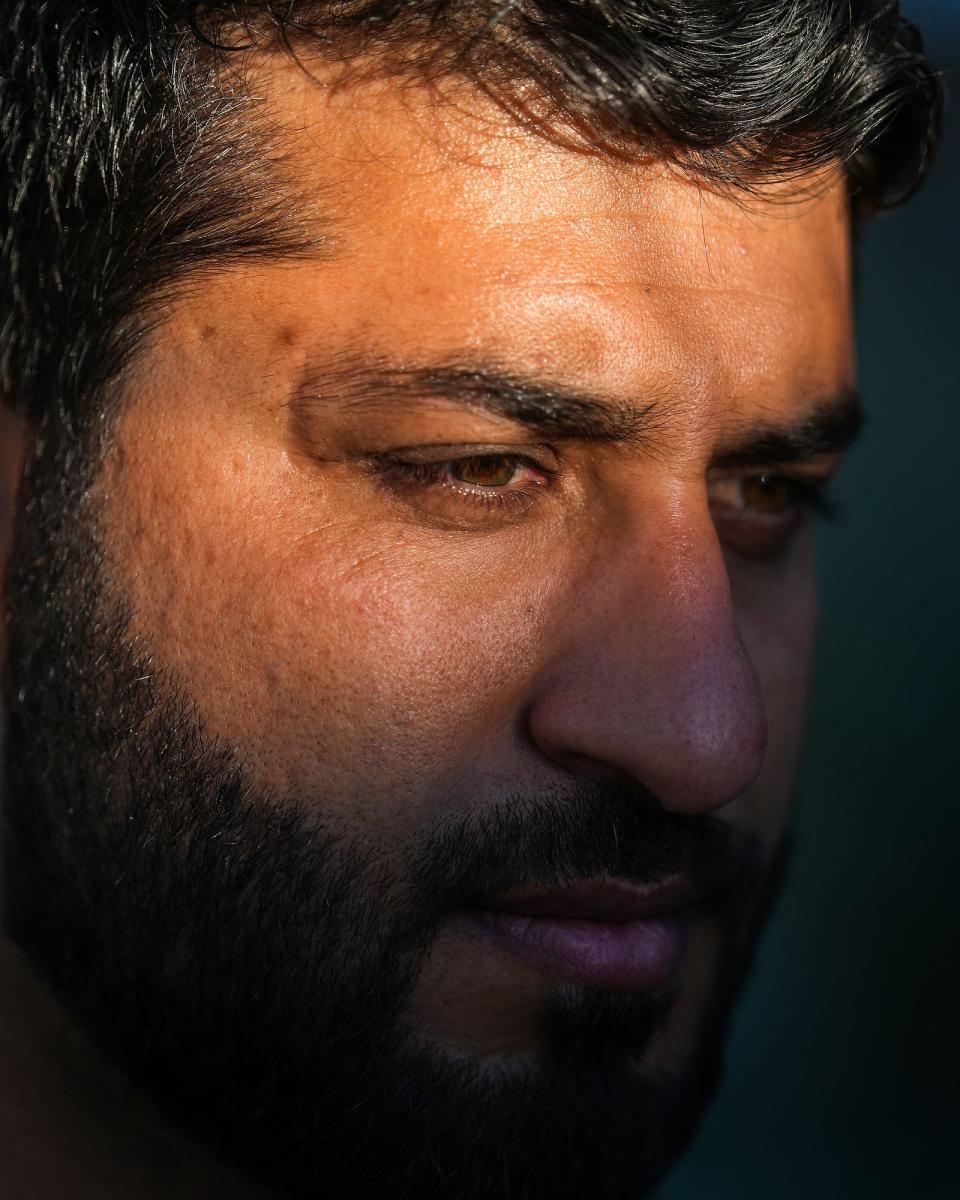

Ahmad Naeem Wakili stares pensively at his phone, scrolling through photos of his old life in Kabul. He's 31 and far from the place he grew up, longing for his wife, Nilofar, and 2-year-old daughter, Kawsar, who are waiting more than 6,000 miles away in Istanbul.

Ahmad had a good life in Kabul, surrounded by family, running his own businesses, a karaoke restaurant and a sports club that he co-owned with a friend.

But his day job sometimes put him in danger. He worked as a junior judge at a U.S. air base that sentenced members of the Taliban and other terrorist groups. Friends of detainees had threatened him and followed through. Ahmad's car had been bombed at the end of 2019 and last year he was shot in the abdomen. He lost a kidney and spent more than 22 days in a coma.

While many people celebrated the end of the 20-year U.S. occupation of Afghanistan, particularly rural Afghans who had been hit hardest by U.S. coalition air strikes, the shift spelled trouble for Ahmad. When the Taliban regained control of the country last August, they freed all the prisoners from the air base, some of whom Ahmad had helped sentence.

Now, Ahmad lives in Tucson. His mom and dad remain in Afghanistan, his brother and sister moved to Pakistan. And his daughter and wife are in Turkey, where he had sent them more than two years ago for safety while he was still working in Afghanistan.

“It’s one family, four countries,” he said. “Can you please tell me who is responsible for this situation?”

He fears for the safety of his wife and daughter. He describes Turkey’s southern border as porous and worries that the same people who threatened his life are looking for them now. Judges have long been a target of the Taliban, according to experts, although there haven’t been any documented cases of Taliban killings in Turkey. The family of his wife, Nilofar, has suffered from Taliban violence: Armed gangs affiliated with the Taliban killed her uncle.

But as Ahmad fights to bring his wife and daughter to Tucson, he’s encountered obstacles every step of the way. The money he sent them was rejected. He struggled to extend his daughter’s Turkish residency permit. He is frustrated at the seemingly endless bureaucracy.

He’s one of 2,053 Afghans who’ve arrived in Arizona since the Taliban conquered Kabul, according to a spokesperson for Gov. Doug Ducey’s Office. About 1,441 of them live in Maricopa County and 612 in Pima County. Refugee and immigration advocates say many other Afghans are dealing with similar problems as Ahmad in a system that’s been underfunded, overwhelmed and “siloed from reality.”

Ahmad’s story

Ahmad said he wanted to be a judge since he was a child after watching scores of Bollywood films where he saw judges on the big screen.

He studied law at Mashal University, and after he graduated and completed one year of practical training, the Afghanistan Supreme Court assigned him to work as a junior judge at the Bagram Air Base, run at the time by the U.S. government. He was 28, one of the youngest judges there.

“Everything belongs to the U.S. military, just the (court) decision belongs to Afghanistan government,” he said.

Under Afghanistan law, it takes three judges to make a decision: a peer judge, a judge and a head of court. Ahmad worked as a peer judge and had the most direct contact with the people on trial.

Ahmad scrolls through his camera roll, showing pictures of himself in a plain room, devoid of the typical dressings of a U.S. courtroom. In one image, he stands surrounded by several members of the Taliban and three security guards.

“When they sent me to the Bagram detention center, it automatically put my life in danger,” he said. “I try a lot to change myself from Bagram to another court. The Supreme Court, this was their answer — what's different between your life and the other life? If I change you and I send another, what’s different between you?”

Once, a member of the Taliban asked him to release someone who was imprisoned. When Ahmad refused, the Talib told him he was playing with his life, he said.

Later that year, they would plant a bomb in his car. A few years after that, they shot him as he was getting out of his car to buy his mother medicine, leaving him to bleed on the road for three hours until his family found out and drove him to the hospital.

The bombing left him in a coma for more than 22 days. When he returned home from the hospital, he found that the Taliban had threatened his family. It was after that he decided to send Nilofar, who was pregnant at the time, to Turkey.

As he scrolls through photos, it becomes apparent that Ahmad wears two rings, one on each hand: on his right is a silver wedding band, and on his left an emerald ring his wife gave him.

Distantly related, Ahmad and Nilofar met several times at different parties, weddings and Eid al-Fitr events. Ahmad asked his mom to see if Nilofar's family would be interested in a marriage, as is traditional custom. Nilofar and her parents agreed, and the couple were married about a year later.

He describes Nilofar as serious, friendly and quiet. She didn’t have the chance to attend university, because her family worried about her security. Her father owned the Green Village compound that rented space to international organizations and was the target of a Taliban attack. Ahmad said she was always interested in computer science and journalism.

He said he has a hard time sleeping at night without her.

“First, she's my friend. After that, she's my wife,” he said. “We’re best friends.”

Their daughter was born in Turkey. They named her Kawsar, a name Ahmad had long admired, after a chapter in the Quran. He beams with pride when he describes her playfulness and curly hair.

Uncertainty for his family

After the last attempt on his life in July 2021, Ahmad lost a kidney. He was in the hospital for only six days, which his doctor said wasn’t enough time, but the hospital was full.

He returned home to recover, and although he wasn’t fully healed, he bought a ticket for Istanbul on Aug. 12 to fly there the next week. He was eager to get back to his wife and daughter, he said. On Aug. 15, days before his flight, Afghanistan’s U.S.-backed government fell.

Ahmad walked about 6 miles to the Kabul airport after the Taliban takeover, one of many Afghans clamoring for a ticket out. He was one of the lucky few who received it. The U.S. guard accepted an expired German travel visa Ahmad had kept from his honeymoon three years ago and Ahmad flew in a military plane to Qatar.

“In Qatar, I cry a lot. I request too much, please I want to go to Turkey, my family’s there,” he said. “They said 'I’m sorry we can’t do it, because you don't have a travel document.' I said, 'I have passport.' 'You have passport, but you don't have travel visa.'"

So while his family remained overseas, Ahmad flew to the United States, eventually ending up in Tucson.

In Istanbul, Nilofar and Kawsar barely leave their apartment, Ahmad said. Nilofar is afraid that if they do, the Taliban might find them. When she does venture out for necessary appointments, like visiting the doctor’s office for back pain, she struggles with a language barrier.

It’s unclear if the Taliban present a threat to Ahmad’s family, according to Patricia Gossman, associate director for the Asia division of Human Rights Watch. She said they would have to travel through Iran first. If Nilofar and Kawsar were to be deported back to Afghanistan, they would be at risk.

“Judges have long been a target of the Taliban,” Gossman wrote in an email to The Republic. “Since he worked at Bagram, he would also be at risk because of his association with the U.S. military. We are aware of Taliban also targeting family members in some cases. However, all the cases I know of occurred in Afghanistan; I am unaware of threats in Turkey.”

Still, Ahmad remains worried about Nilofar and Kawsar, citing the large number of Afghans, most of whom are fleeing the Taliban, who have migrated to Turkey.

“I’m worried because I know,” he said. “I saw Turkey.”

Tucson City Councilman Steve Kozachik, who represents Ward 6, has been a passionate advocate for Ahmad. Kozachik said he receives messages daily from Afghans abroad who have received threats from the Taliban.

“The experts are not in touch with people on the ground,” he wrote in an email. “Realize that Ahmad was in a very political position — that makes him and his family targets.”

Immigration: U.S. Citizen and Immigration Services extends length of work permits

Advocates: U.S. not prepared for Afghans

Ahmad met Kozachik at the Red Roof Inn, a small hotel many Afghans were assigned to live in when they first arrived in Tucson. Kozachik came to know several Afghan refugees after helping a local mosque deal with harassment. College students who lived nearby pelted whisky bottles at the mosque. The mosque has a sizable refugee population and Kozachik soon began helping out.

After getting to know Ahmad, Kozachik asked him to perform the swearing-in at his city council inauguration this past December.

“I want to say thank you to Steve,” Ahmad said. “Because in the U.S. I don't know anybody. And he's trying his best to to help me and I know he ask different people to unite me with my family.”

Kozachik and other refugee and immigration advocates say the burden of resettling refugees falls to local communities, faith organizations and non-profits. They’ve decried the lack of resources from the federal government.

“When our federal government says that we have resettled 71,000 Afghans, my answer is you haven't resettled any,” Kozachik said. “All you're doing is you're dumping them on local jurisdictions and saying you figure it out. And so this whole notion that the federal government is involved in its resettlement effort is a complete farce. It's local people, it’s communities and it’s groups like this who are doing the work on the ground.”

Local communities have been hit with competing challenges, including skeleton-infrastructure and a more recent unexpected surge in refugees.

The Trump administration lowered the ceiling to accept only 18,000 refugees during the 2020 fiscal year and attempted to lower it even further, to 15,000 refugees, the lowest level yet, during the 2021 fiscal year. When Joe Biden was elected, he changed the cap, raising it to 62,500 refugees in 2021.

But the Biden administration fell short even of Trump’s ceiling, accepting only 11,411 refugees that year. Now, Biden is attempting to raise the cap to accept 125,000 refugees during the 2022 fiscal year, which refugee advocates say they’re not prepared for.

Mahmoud Alabagi, the executive director for Hasanaat Development Center, a Tucson-based education and post-resettlement agency, said resettlement agencies are overwhelmed.

“These are huge increases. And that's fantastic and I hope they continue to increase,” Alabagi said. “But where are the systems? Where are the refugee resettlement agencies? Where are the dollars that support these organizations that allow these people to be successful?”

After the Trump administration cuts, resettlement agencies were stripped to skeleton staff, or closed down altogether, according to Diego Piña-Lopez, program director for Casa Alitas, a Tucson-based non-profit for asylum seekers.

It’s meant that federal dollars — the $1,225 that resettlement agencies receive per refugee to provide months of housing, food, clothing, transportation, English-language classes and mental health services — weren't dispersed quickly.

The lack of infrastructure was made worse by the short notice resettlement agencies and non-profits were given about the surge of Afghan refugees.

Refugee and immigration advocates have said they’ve been dealt an impossible hand, resettling Afghans with two weeks notice, sometimes less. Agencies typically have a couple of months notice, they said.

Families, sometimes consisting of as many as nine people, have lived in one-bedroom hotel rooms for months because of the late notice, according to Alabagi.

“I've worked with refugees that have come from different countries where the U.S. was not directly involved, Syria is a good example of it, and that resettlement process was significantly better than the botched process of bringing the Afghans here,” Alabagi said.

Alabagi also said he’s seen less community support for Afghans as opposed to other refugee communities he’s worked with, like the local Syrian, Iraqi and Somali communities.

He said it’s twofold: first, the public’s disappointment that the United States spent years in Afghanistan with little success. And second, the negative media reports about Afghans and the Taliban.

"When someone hears that someone's (married off their daughter), they villainize that person. But we don't really look at the underlying picture of what brought that person to that decision," he said. "Literally not eating for days, and seeing your children and your spouse dying in front of your eyes. You have to do something … But the reality is, is that Afghans are like any other community. They are wonderful people who went through hell and back and come to the United States as a land of opportunity.”

Kozachik added, “I think there is still an anti-Muslim sentiment in this country that really escalated during the Trump administration and I don't think that's gone away.”

While Ducey and Arizona House Speaker Rusty Bowers put out a statement saying the state is “ready to welcome” Afghan refugees, quoting the Bible, several Arizona politicians have criticized the state’s acceptance of Afghans, falsely calling them unvetted.

Recently, the International Rescue Committee delayed the enrollment of over 80 Afghan children in Scottsdale Unified School District. They wanted to give refugee families time to understand “what they were walking into,” superintendent Scott Menzel wrote in a letter, reported by the Arizona Capitol Times, after conservative critics of the school district criticized the acceptance of refugees into an “overburdened” school district.

Alabagi said in the eight years he’s been involved with refugee advocacy, the work of providing refugees with meals, furniture, cultural immersion and other necessities is performed mostly by local communities.

“It has to come from the heart. ... I don't sense the same excitement from volunteers about Afghan refugees than I did from refugees of different backgrounds,” Alabagi said.

State of the Union: Advocates see urgency in urgency to pass immigration reform

‘Counseling patience’

Kozachik has tried repeatedly to reunite Ahmad with his wife and daughter. He’s contacted two of Tucson’s congressmen, both of Arizona’s senators, a former Tucson police chief-turned-commissioner for U.S. Customs and Border Protection, the City of Tucson’s D.C. lobbyist, a local immigration attorney, a volunteer on the ground in Turkey and several others. He’s reached out to the news media.

Still, the needle hasn’t moved much, he said.

Kozachik called resettlement a bureaucratic process siloed from reality. He warned that “counseling patience,” which is what he said the State Department advised him when he contacted them about Ahmad’s case, is going to get people killed.

“We have a consulate, we have an embassy and we have a military installation, literally within minutes of where (Nilofar) is in Turkey,” he said. “Somebody get in a car, drive over there, pick her up, put her on a C17, get her to Frankfurt. And I said I'll pay for the plane ticket. Istanbul to Frankfurt to Heathrow to LaGuardia to Sky Harbor. Boom, done. Doesn't cost the taxpayers a penny, we’ll pay for it.

“They said we've got protocols to follow,” he said. “(Senator Mark) Kelly's general counsel told me we have lots of people in this situation. I said, ‘You don't have lots of people whose … car's been bombed, who's been shot and ready to take his wife into Turkey because he was working for us at Bagram. And he's a target because of his work for us. You don't have lots of people in that situation.’”

To get Nilofar and Kawsar to the United States, Ahmad has had to deal with eight U.S. and international agencies.

First, there was the matter of extending Kawsar’s Turkish residency permit. Nilofar and Kawsar’s residency permits expired in December 2021 and the Turkish government gave them a month to gather the necessary documents to extend their permits. If they’re deported back to Afghanistan, their lives would likely be at risk, according to Ahmad, Kozachik and Gossman.

Under Turkish law, a father has immediate legal power over his children. Since Ahmad isn’t in Turkey, and can’t fly to Turkey because he wouldn’t be able to return to the U.S. if he leaves, he needs to grant Nilofar legal power over Kawsar to extend her residency permit.

Granting Nilofar legal power has induced its own wave of challenges, taking two months to obtain and leaving them without legal documentation for a month. Ahmad either needed to transfer power through the Turkish consulate, or he could write a letter to the Turkish government, get it notarized by the city clerk and then ask Arizona’s secretary of state to affix an apostille stamp.

He emailed and called the Turkish consulate in Los Angeles several times, but said he didn’t receive a substantial response until Kozachik got a United Nations official to email.

So Ahmad wrote a letter and tried to get an apostille stamp affixed, which is done by Arizona’s secretary of state. But because of COVID-19 precautions, neither the Phoenix or Tucson offices take appointments in person. Ahmad and Kozachik had to mail in an application, which has a 10-day delay.

Nilofar and Kawsar’s residency permits had expired by this point, and Ahmad was afraid they would be deported back to Afghanistan.

When The Republic contacted the Arizona Secretary of State’s Office, officials said they never received a request for Ahmad Wakili, which Kozachik said illustrated how “messed up” the process is.

Nilofar and Kawsar finally received a one-year residency extension on Feb. 21.

After much nagging, Kozachik said, the State Department placed Nilofar and Kawsar on a family reunification list in December, along with 115 other Afghan families stuck in Turkey. But when Kozachik asked what the list means practically — What processes do Nilofar and Kawsar still have to go through? When can they enter the United States? — the department official said he didn’t know yet and again asked Kozachik to be patient.

Kozachik also highlighted issues that he said should be easy for the State Department to deal with, but presented a challenge for Nilofar and Kawsar. For example, the State Department said Nilofar had to translate Kawsar’s birth certificate from Turkish to English to include it in a United States Citizenship and Immigration Services application for humanitarian parole, the legal status Nilofar and Kawsar must claim to come to the United States.

Kozachik wondered why one of the Turkish translators at the State Department couldn’t do it.

Kozachik also contacted the offices of Rep. Raúl Grijalva, Rep. Ann Kirkpatrick, Sen. Mark Kelly and Sen. Kyrsten Sinema seeking help.

Abigail O’Brien, a spokesperson for Kirkpatrick, said their office wrote official letters on behalf of Ahmad, but they could only do so much because it’s the State Department’s domain.

“We expedited and did everything we can at the pace we could,” she said. “These things are at the State Department level, we act as the middle liaison between constituents and federal entities.”

And then there were money issues.

Kozachik took Ahmad to a Western Union bank, where he tried to send money to Nilofar and Kawsar. But the bank rejected the transfer because his only identification at the time was an Afghan passport.

Money transfer companies initially suspended transfers into Afghanistan, hoping to avoid running afoul of U.S. sanctions on the Taliban. There were never any official restrictions on sending remittances, but to put money transfer companies at ease, and with a mounting hunger crisis in Afghanistan, the Treasury Department issued formalized guidance in December.

Kozachik provided his driver’s license to Ahmad so he could wire the money to Nilofar and Kawsar. Ahmad later received a U.S. driver’s license and was able to send money to Nilofar and Kawsar by himself.

Kozachik has asked authorities to ease the administrative burdens of this process, noting that the U.S. didn’t adhere to normal, arduous vetting procedures when they allowed desperate Afghans onto American military planes this past August after the Taliban takeover. They recognized the emergency of the situation, he said.

While Afghans were allowed to evacuate the country, the U.S. government still requires them to go through a rigorous vetting process at military bases, including fingerprinting and interviews with government officials.

Kozachik said he’s lost count of the number of hours he’s spent trying to figure out the system and he’s criticized the State Department, calling them “unapproachable, unreachable and unaccountable.”

“This has gotten to be a really emotional journey. And I'm awake at two o'clock, three o'clock in the morning often times, worried about them. I don't know (Nilofar), but I feel like I do now. We just got to be better than this,” he said.

“If we can't set our rules aside and literally save these two people's lives, then why are we even doing these jobs? And I mean it. I mean that from my level, to the people in the White House, the State Department, our congressional offices, our senators, how can we possibly have a system that’s so broken, that when somebody risked their lives on our behalf, that one of our congressman's offices tells me, ‘We have protocols to follow.’ There's nothing right about this.”

Ahmad worked for awhile as a parking garage attendant and now works as a case manager for Tucson’s chapter of the International Rescue Committee. After his day ends at 5 p.m., he calls Nilofar. It’s 3 a.m. in Istanbul, and they talk for a couple of hours before she falls asleep.

“It's just a short story that I’m telling, because my English not very well. If it's in my own language, I will tell you all the story, it will be very interesting and very tough,” Ahmad said. “You know, my life, it seems like a movie. When I want to tell my story to somebody, they don’t accept it, you’re just telling a story. But it’s real.”

Kozachik turned the lobby of his 6th ward office into a makeshift supply closet for local refugees, featuring piles of clothes and other banal household objects. After his interview with The Republic, Ahmad left the office carrying out a prayer rug in one hand, and a small wooden chair for his daughter in the other.

Zayna Syed is an environmental reporter for The Arizona Republic/azcentral. Follow her reporting on Twitter at @zaynasyed_ and send tips or other information about stories to zayna.syed@arizonarepublic.com.

This article originally appeared on Arizona Republic: An Afghan judge who sentenced Taliban members waits for his family