Judge grills Mass. state troopers over illegal, undisclosed audio recordings

More than 60 Massachusetts state troopers made “covert investigative recordings” in recent years that were never turned over to prosecutors and in many cases violated the state’s wiretapping law, documents obtained by the Telegram & Gazette show.

The recordings, which mostly appear to have been made during drug investigations, were made in more than 250 criminal cases, the documents show, including cases brought by local, state and federal prosecutors.

“That we’re even here, frankly, is shocking to me,” Christopher P. LoConto, first justice of the Fitchburg District Court, said during a recent court hearing on the recordings in which he asked pointed questions of current and former troopers under oath.

It was while discussing a Fitchburg drug case with an undercover state police detective in 2023 that local prosecutors first learned troopers had made, but failed to disclose, audio and video recordings of drug purchases.

Prosecutors are legally bound to provide defendants with any evidence of their statements, and a failure to do so could open the door to court challenges or civil lawsuits that could threaten convictions or lead to monetary damages.

As the Telegram & Gazette reported last year, Worcester County District Attorney Joseph D. Early Jr.’s office, after learning of the undercover officer’s recordings, informed members of the defense bar and asked state police for more information about what happened.

Since that time, state police conducted an audit that found that more than 60 troopers made recordings they never disclosed to prosecutors in more than 260 cases dating to at least 2013, a June 2023 state police memorandum shows.

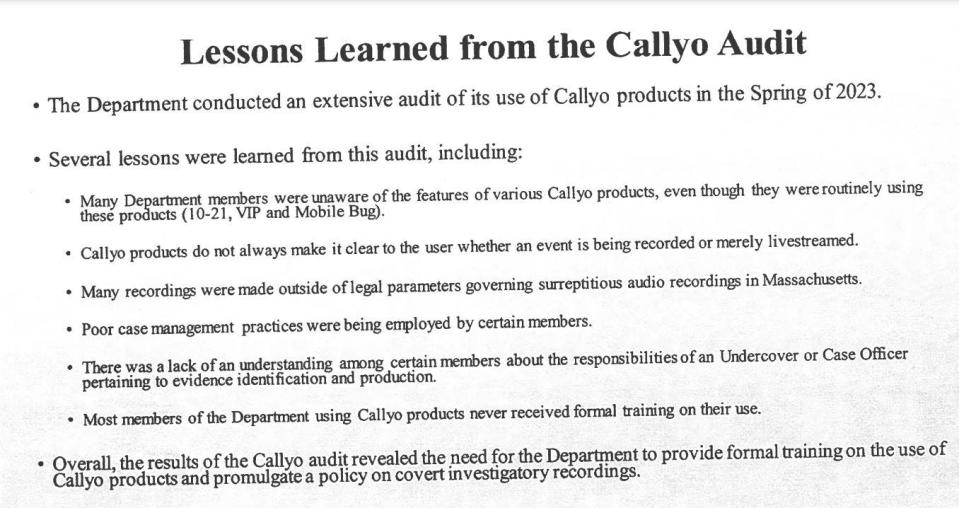

“Many recordings were made outside of legal parameters governing surreptitious audio recordings in Massachusetts,” state police wrote in a training document summarizing “lessons learned” from the probe.

The review shows that state police have never had a policy regarding covert audio recordings, and that the department, despite acquiring technology in recent years that allowed officers to secretly make recordings on their smartphones, never trained officers in how to use it.

“This is a failure of the state police in terms of giving out equipment and not providing training,” LoConto remarked at one point after hearing testimony from multiple troopers.

LoConto has conducted three hearings since November in which he has questioned troopers under oath in connection with requests from defendants for new trials.

Audio the T&G reviewed of the hearings show LoConto made clear his frustration with the answers troopers, as well as state police lawyers, have provided to his questions.

The state police — which, the documents show, have since created a policy on the use of covert audio recordings and required training — did not return a set of questions sent to a spokesman Monday.

Among the queries was whether the department expects any high-profile cases to potentially be impacted by the undisclosed recordings.

According to a list of docket numbers of potentially impacted cases contained in the police memorandum, undisclosed recordings were made in cases in superior courts throughout the state, as well as more than a dozen cases in federal court.

One of the cases listed is that of Vincent “Fatz” Caruso, a Salem man sentenced to more than 20 years in federal prison in June 2022.

The office of U.S. Attorney for Massachusetts Joshua S. Levy, which in a news release described Caruso as a Crip-associated leader of a “violent fentanyl pill trafficking organization,” declined a request for comment.

Federal law is less stringent than Massachusetts law on secret recordings — it only requires one party's consent to the recording — so it was not immediately clear whether any federal case could be impacted.

There did not appear to be any docket entries in Caruso’s case indicating his defense had raised the issue since his conviction.

Police say recordings linked to safety concerns

The recordings under scrutiny are connected to a Motorola-based smartphone application, Callyo, that law enforcement across the country use during drug investigations.

The application, which supplants use of the more dangerous physical wires police formerly used, allows officers to use their phones as covert recording devices, marketing materials show.

Testimony in LoConto’s court indicates that the company defaults the application to audio- and, depending on the app, video-record the interactions. Marketing materials show the company has touted the technology in assisting in prosecutions.

But Massachusetts law, unlike most other states, makes covert recordings illegal under its wiretapping law and, with limited exceptions for officer safety, requires police to get warrants before recording undercover operations.

Troopers testifying in LoConto’s hearings said they’ve been using Callyo for about five or six years. Their prime goal, they said, was to monitor the application, which allows real-time streaming of audio and sometimes video, to ensure officer safety during drug buys.

Some of the troopers testified they didn't initially know the application was recording — they only thought it was streaming — though it appeared that all eventually were made aware of the capability during the investigation.

Questions by defense lawyers and LoConto during the hearings indicated the videos were also used for investigative purposes in Fitchburg drug investigations, and the judge asked troopers why they would need to record the operations if their prime goal was safety.

Troopers questioned agreed that the undercover trooper who made the Fitchburg videos did not initially provide them to prosecutors, and that law enforcement never mentioned the existence of the videos in their reports.

Troopers, including a supervisor, told LoConto and defense lawyers that different drug units had different practices on report writing and undercover work, and gave answers to probing questions that the judge found lacking.

“It’s shocking to me that these are the answers I’m getting,” he said at one point when speaking to a state police lawyer about his efforts to get answers to some questions he saw as basic regarding responsibility for turning over evidence.

“These are relatively simple tasks to complete. Producing evidence, turning over evidence.

"It’s very simple,” LoConto said. “And no one’s in charge, and no one’s responsible.”

LoConto specifically homed in on the lack of mention of the recordings in police reports.

“You want me to believe that was accidental?” he asked at one point of a state police lawyer, who said that was the judge’s discretion to determine.

LoConto was sharply critical at times in his remarks about the state police, who told the judge that interim state police Col. John Mawn Jr. did not appear for a requested subpoena from defense lawyers because the department determined the subpoena was not legally valid.

“You can’t ignore the summons because you don’t think it’s valid,” LoConto said at the first hearing Nov. 29. “If you don’t believe the summons is valid, you come to the court.

“Rules apply to everyone.”

Mawn has not testified in the case, and later court proceedings show LoConto did not appear inclined to believe his testimony was necessary.

Supervisor: 'Not too good with policy'

LoConto did hear from a supervisor of the Fitchburg drug operation in question, retired Sgt. Gregg Desfosses, at a hearing Jan. 17.

Desfosses testified he had told troopers involved in the probe they needed to acquire warrants to record in the past, but that he wasn’t familiar with the recording capabilities of Callyo because he never received training on it.

Desfosses acknowledged he became aware of the recording capabilities during the investigation, however, when the undercover officer forwarded a photograph of a target to him and other troopers for investigative purposes.

He testified he did not make further inquiries about the recordings, or alert prosecutors about them, saying it was “not my responsibility.” He said multiple times under questioning that he was not a “micromanager.”

At one point during questioning, LoConto asked Desfosses, who served for more than 25 years, whether he knew if state police have a policy on whether troopers have an “affirmative obligation” to turn over evidence.

“To be honest with you, your honor, I don’t know if it’s specifically written in the policy. I’m not too good with policy and procedure,” Desfosses replied. “But I believe that there would be something that — yes, troopers are required to turn over evidence to the district attorney’s office, yes.”

Desfosses testified it was generally the responsibility of case officers — in this case, Trooper Justin Burd — to transmit such information to prosecutors.

Burd, asked whether it was his “training” to wait to turn over evidence to prosecutors until “asked” for things specifically, replied: “Typically, the way that — I don’t want to say trained, but culturally examined, would be that I would wait until I was asked.”

Burd testified that, while the undercover officer mentioned the Callyo technology during briefings prior to operations, he didn’t initially know it could record, or was being recorded.

LoConto at one point noted that email records showed Burd and other troopers were sent photographs of people by the undercover officer asking who they were.

The judge, in questioning Burd directly, asked how, other than secretly recording, he thought the undercover trooper could have obtained photographs of his targets.

“You’ll have to ask him that. I don’t know, sir,” Burd replied.

LoConto then asked whether, in Burd’s experience, a person selling drugs would be OK with someone taking out their cellphone and shooting a picture of them.

“No,” Burd replied.

Burd ultimately agreed he should have known what to do once he was aware of recordings being made, but stressed that state police gave him no training.

“As far as the video goes, I was completely ignorant to any policy, any training, any supervisory direction on what to do with this type of evidence,” he testified.

Documents obtained by the T&G show Mawn, June 29, 2023, promulgated a policy governing the use of covert audio recordings in the department.

The policy states troopers will be, among other things, trained with the capabilities of the recording technologies they use, will not initiate secret recordings without supervisory approval absent emergency circumstances, obtain a warrant or prosecutorial approval before making a secret recording, obtain written authorization from federal prosecutors before making secret recordings in federal cases, and document the existence and supervisory approval of all secret recordings within a written investigatory report.

In training documents obtained by the T&G regarding “lessons learned” from their investigation, state police found “many troopers weren’t aware of all the functions of the Callyo suite of applications, that “poor case management practices were employed by certain members” and that there was a “lack of understanding among certain members about the responsibilities of an undercover or case officer pertaining to evidence identification and production.”

Court testimony indicated the department has opened internal affairs investigations into some troopers in connection with the recordings, and internal investigators were present in LoConto’s courtroom during testimony.

LoConto to rule on Fitchburg cases

LoConto’s hearings regarding the Fitchburg drug cases in which illegal recordings were made is slated to continue in March.

The judge will be tasked with issuing a ruling on whether to grant motions for new trials in about half a dozen cases from a drug sweep state police conducted with members of the North Worcester County Drug Task Force in the winter of 2022.

Court records and testimony show most of the people charged in the sweep were low-level drug users charged with selling small amounts — usually $100 or less — worth of heroin, cocaine or fentanyl to the undercover trooper.

None of the defendants received significant jail time, and LoConto stayed any jail sentence or probation terms after the existence of the recordings came to light.

Court records show defense lawyers in the cases have requested and been granted thousands of dollars in public funds for transcripts and other posttrial motions as a result of the disclosures.

Documents show cases in which secret recordings were made include cases across the state and in nearly a dozen case prosecuted by the attorney general’s office.

The AG's office declined to comment. An offer of comment to the Massachusetts District Attorneys Association lodged Monday had not been returned as of Tuesday morning.

The Committee for Public Counsel Services, the taxpayer-funded entity that represents indigent defendants, declined to comment Tuesday, noting the ongoing nature of the litigation.

In addition to representing clients in the Fitchburg hearings and in other affected cases, the committee recently sued state police under the Massachusetts Public Records Law, including for records related to the Callyo investigation.

This article originally appeared on Telegram & Gazette: Mass. state troopers found making illegal audio recordings with app