Should judge in Megan McDonald case have stepped aside, because of brother-in-law?

Jason Rivera needed legal advice sometime after 2008. State Police investigators wanted to question him in connection with the 2003 Megan McDonald homicide.

Legal help was a phone call away, in the form of his brother-in-law, attorney Craig Stephen Brown.

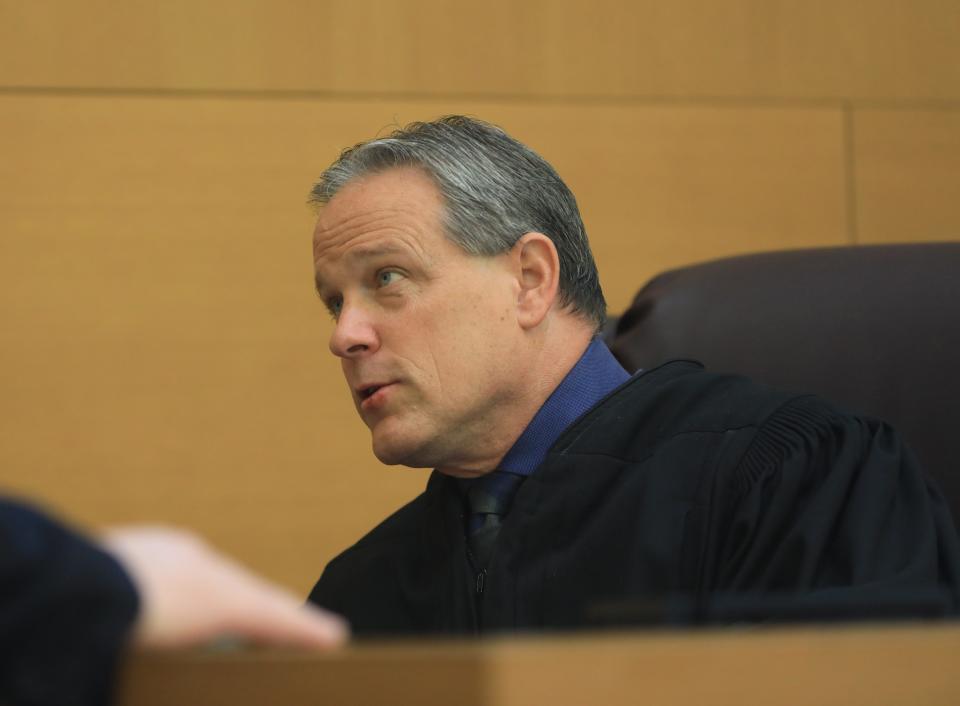

Brown says he represented Rivera and that Rivera was questioned. But police records don't show Rivera being interviewed in the McDonald case until after another phone call, one Brown placed years later, after he had been elected Orange County Court judge.

It is that phone call, made in early March 2019, that caught the attention of State Police investigators and changed the way Brown was perceived by some at the police agency, in connection to a case where mistrust was already running high.

The call, and the mistrust, came to light in a blistering internal State Police report that also accuses District Attorney David M. Hoovler of deliberately tampering with the investigation into the 20-year-old woman's bludgeoning death in March 2003. The report says Hoovler once sought a plea deal for a man named Andre Thurston, a man State Police believe was in the car when McDonald was murdered.

Hoovler has denied hindering the investigation in any way, calling it "as categorically false as it is offensive."

But the accusations in the report clearly demonstrate the disconnect between the DA and the police, perceptions and perspectives that led to a wild chain of events. Edward Holley was arrested on April 20, 2023, and charged with second-degree murder in the case, without Hoovler's office having been consulted. The DA then recused himself and veteran Westchester prosecutor Julia Cornachio was named special prosecutor. On Jan. 29, 2024, the Orange County grand jury handed up a single second-degree-murder indictment of Holley.

Holley has proclaimed his innocence in the homicide.

A warrant sought, a phone call made

But back to that phone call.

That part of the story began in mid-2018, when police sought an eavesdropping warrant to monitor Edward Holley's phone.

DA Hoovler said if it met his conditions and narrowed the focus only to Holley, he'd approve it. The report says Hoovler said he would present the affidavit to Brown because “Judge Brown will approve the warrant if Hoovler approves.”

Brown began his career as an assistant district attorney in Queens County and in private practice in New York City before joining the Orange County DA’s office in 2003. During his time there, Brown was in the violent felonies and investigation unit. Another ADA at the time was David Hoovler. Hoovler was elected DA in 2013; Brown was elected county judge in 2016.

It took police nine months to get the warrant ready and when they did, it went from police to executive ADA Chris Borek to the judge’s clerk and then to Brown.

In a phone interview in late January 2024, Hoovler explained how his office handles warrant requests.

“Generally a judge's law clerk asks in advance for a copy of what you're going to bring, because the judge and their law clerk generally will read it for a couple days before, and stew on it before they decide what they want to do with it,” Hoovler said. “That wiretap application was specifically constructed to what the State Police wanted. Its timing was done based on what they wanted. They wanted it done at a particular time. And it was presented to us. It was put together and it was taken to the judge. I did not take it to the judge.”

For a wiretap warrant, Hoovler said, he’ll have one of his executive ADAs review the application.

“They note any changes, alterations or deletions they want. After they do that, they give it to the judge, and then the judge either indicates 'send somebody up to clarify more' or whatever's going to happen with it. But Chris Borek handled that application. He went up and he handled it with Judge Brown.”

In the days before Brown was asked to handle a warrant application in the same case he'd advised his brother-in-law about, he picked up the phone and called Senior Investigator Kevin Chorzempa, and asked a question, off the record.

Chorzempa and Brown were friends on Facebook, their kids played sports together. But in a phone interview with the USA Today Network New York, Brown said he called Chorzempa because "he was one of the people that reached out and interviewed my brother-in-law for background information. So I thought he would be in the best position to tell me."

Brown says he asked if Rivera was sought as a background witness or a material witness.

Chorzempa — who had long since moved off the McDonald case and away from State Police Middletown and now works at State Police Ellenville — reported the phone call to his superiors. The internal report says the judge asked Chorzempa if Rivera "was a suspect" in the homicide.

"Senior Investigator Chorzempa was not aware of the status of the investigation because he was no longer a member of the SP Middletown BCI (Bureau of Criminal Investigation)," the report reads.

Chorzempa declined to comment for this story, citing the ongoing investigation. Spokesman Steven Nevel at Troop F in Middletown, where the McDonald investigation was handled, and Deanna Coates, acting director of public information at State Police headquarters in Albany, said no member of their force would speak about an ongoing case. Not Lt. Brad Natalizio, the report's author. Not lead investigator Michael Corletta. Not Capt. Joe Kolek.

MEGAN MCDONALD TIMELINE: Follow the case's twists and turns

Click on the right arrow below to see how the investigation evolved

Why the phone call matters?

The phone call mattered to police because within days of placing it, Brown on March 12, 2019, declined to approve a key search warrant that would have granted State Police permission to tap Holley's phone, opening a possible trove of information. Brown based his denial on a lack of probable cause.

Hoovler, in the 2024 interview, clarified: “It was denied because the probable cause was stale relating to a 20-year-old conspiracy.”

The internal report suggests Brown's call made State Police investigators lose faith in the judge, faith that was further shaken in 2020 when he once again denied a search warrant, for Holley's Google accounts.

Within days of the phone call, and six days after Brown denied the eavesdropping warrant, Jason Rivera makes his first appearance in the McDonald case interview list, on March 18, 2019. He was then twice questioned by police, invoking his relationship with his brother-in-law judge in both interviews.

'No one asked me to recuse'

Brown, interviewed by the USA Today Network New York last fall, said the reason for his call was simple.

"I called to confirm whether or not I needed to recuse," Brown said in an October 2023 phone interview. "That's why I called. That's the only reason I called. And no one asked me to recuse."

Judges regularly recuse themselves from cases where they have a connection, either through past representation, financial interests or some personal link. When a judge recuses himself or herself, the case goes to another judge. Happens all the time.

"If someone is brought in for background and there's no indication that they have anything to do with it other than that, that's why I needed to know the answer to that question in order to make an informed decision," Brown said. "It seems to make sense to me."

Brown was asked about the optics of the question he asked Chorzempa, if the very asking of the question was an answer in itself about whether the judge should recuse himself. He didn't see it that way.

"Because the interviews appeared to be background not related to him being a witness or him being a suspect," Brown said. "So if that were the case, then there is no appearance and there is no conflict. So I was calling to confirm whether or not S.P. (State Police) had information that that would give rise to my recusal or not."

Asked what Chorzempa replied, Brown bristled.

"Well, I'm not going to go into my conversation with him, but no one asked me to recuse, is what I'm comfortable saying," the judge said. He also pointed out that he ruled in favor of police on other matters in the McDonald case, without going into detail.

A troubling timeline

The report presents the timeline of that wiretap request — warrant is completed by State Police and prosecutors, judge asks about brother-in-law's connection to investigation, judge denies warrant — and raises ethical concerns.

Brown judges it differently.

"The timing of the call was to confirm whether or not S.P. had any information that would lead to me recusing," he said. "Because as far as I knew, there was no reason for me to recuse. So the only people that would be in a position to know that would be S.P. who was bringing the application before me. That seems to make sense to me."

Rick Trunfio spent more than 30 years in the Onondaga County District Attorney’s office, retiring as first chief assistant district attorney, responsible for the day-to-day operations of the office, with 50 assistant district attorneys. Before that, he was a prosecutor in Philadelphia and was in the Navy’s JAG Corps.

Now, he’s an adjunct professor at Syracuse University School of Law and Maxwell School of Citizenship and Public Affairs and travels the country training prosecutors and members of law enforcement.

Trunfio said the Brown timeline, if true, is troubling when viewed against New York’s judicial code of conduct, written to ensure the highest level of ethical dealings, to render the judiciary beyond reproach.

Section 100.2 of that code states: “A judge shall avoid impropriety and the appearance of impropriety in all of the judge's activities.” It goes on to specify, in 100.2(b): “A judge shall not allow family, social, political or other relationships to influence the judge's judicial conduct or judgment.”

The judicial code also appears to rule out the sort of phone call Brown is alleged to have made to Chorzempa, which Trunfio called “ex parte” communication.

In Section 100.3B, it states: “A judge shall not initiate, permit, or consider ex parte communications, or consider other communications made to the judge outside the presence of the parties or their lawyers concerning a pending or impending proceeding.”

Brown said the communication was not "ex parte," since "there was no one else to bring into it."

But what is clear is that the judge didn’t reach out to Chorzempa about the warrant specifically, but about his brother-in-law.

'It is the judge's decision to recuse'

Trunfio said the phone call and Brown’s continued involvement in the McDonald case are cause for concern.

“When a judge recognizes a conflict such as that, where he actually makes a call to the agency who's applying for that warrant, asking whether his relative is involved, it may have been more prudent to have disqualified himself and immediately transferred that to another judge or notified them that he could not act on this warrant.”

Trunfio continued: “In many situations, only the judge will know or be aware of an issue that may be or result in a conflict. Ultimately, it is the judge’s decision to recuse, but certainly, the judicial code of conduct offers the rules and guidance.”

The New York State Judicial Code's section 100.3E deals with disqualification of judges, and begins: "A judge shall disqualify himself or herself in a proceeding in which the judge's impartiality might reasonably be questioned, including but not limited to instances where..." and then goes on to enumerate them.

Those instances that could touch on the Rivera case could include:

100.3E (1) (a) (ii) the judge has personal knowledge of disputed evidentiary facts concerning the proceeding;

100.3E (1) (b) the judge knows that (i) the judge served as a lawyer in the matter in controversy;

100.3E (1) (d) the judge knows that the judge or the judge's spouse, or a person known by the judge to be within the sixth degree of relationship to either of them, or the spouse of such a person: (i) is a party to the proceeding; (ii) is an officer, director or trustee of a party.

Nowhere in the judicial code is it suggested that a judge call police to ask if they think he should recuse himself.

Rivera questioned

Days after Brown denied the eavesdropping warrant, on March 18, 2019, State Police investigators questioned Rivera. According to the internal report, Rivera told them his brother-in-law was Judge Brown and that they have a close relationship. He told them that he knew Holley because they used to play basketball together at Square Park in the Town of Wallkill.

The report calls Rivera “a key person of interest in this investigation due to his relationship with the main suspect during the timeframe of the homicide.”

A year later, on March 26, 2020, Natalizio submitted a search warrant for Holley’s Google account to Assistant District Attorney Christopher Kelly. For the next year, Natilizio revised the warrant to address concerns from the DA’s office. Once again, the warrant affidavit ended up on Judge Brown’s desk.

In late 2020, Kelly told Natalizio that Brown did not want to sign the Google warrant. Natalizio then worked with ADA Leah Canton to fix the warrant, “with the hopes of the warrant being signed by Judge Brown.”

Brown rejected it for lack of probable cause, the same rationale he gave for rejecting the eavesdropping warrant in 2019.

‘Perceived conflict’

On Nov. 2, 2020, Natalizio and fellow investigator Michael Corletta met with Canton and Kelly. They told the ADAs that State Police did not feel comfortable with Judge Brown reviewing warrants for the case.

On May 5, 2022, State Police investigators interviewed Rivera again. Rivera reminded them that his brother-in-law was Judge Brown and that they had a close relationship. In fact, he told them, “after his March 2019 interview regarding this case, Brown asked him what the State Police were ‘fishing for.’”

Trunfio, at Syracuse Law, said that if what Rivera told police is true, Brown being involved in the McDonald case raises concerns.

“The way I read the rules, any judge who has had conversations with a witness or a person of interest in a pending case or investigation and asks such a question — 'What are they fishing for?' — may indicate a conflict that would trigger that case going to another judge,” Trunfio said. “If I were a judge in that situation, I would have recused myself to be on the safe side.”

Brown did not recuse himself.

According to the report, he took the first warrant request — and denied it — after calling to ask about Rivera’s role in the homicide. He took the second request — and denied it — in late 2020, more than a year after he asked Rivera what police were fishing for.

A judge's discretion

On May 13, 2022, Natalizio and Corletta met with Kelly and Canton, with new evidence: phone calls between Holley and his wife in Orange County jail. The investigators felt the calls bolstered their probable-cause claims and might revive the Google warrant that Brown had denied. Kelly and Canton said they were dubious, but said they would ask Judge Brown’s law clerk about it and report back.

In a sign of the distrust the investigators had for Brown, “Natalizio asked them if they could ask the law clerk without mentioning what case, due to the perceived conflicts that the State Police felt Judge Brown has in this case.”

Trunfio said the way investigators felt — given Brown’s phone call and his relationship to a witness — was one of the specific situations that the Rules of Judicial Conduct are designed to address. But, he added, the fact that the investigators perceived a conflict doesn’t necessarily mean Brown’s rulings were incorrect.

“The warrants could have very well lacked the evidentiary proof necessary to satisfy the requirements of the 4th Amendment,” he said.

After making and clarifying his statement to the USA Today Network New York about why he placed the phone call, Brown referred further questions to the Office of Court Administration, which oversees the state's judges.

Al Baker, OCA communications director, was presented with four pages of questions, including Brown's responses and direct questions the judge declined to answer, questions about DA Hoovler's role in the warrants.

Baker offered the following statement: “Decisions on recusal are made by individual judges, in accordance with the Rules of Judicial Conduct and the discretion of the judge. Because this is a pending matter it would be inappropriate to comment on any substantive issues.”

Brown continued to be involved in the McDonald case. Special prosecutor Julia Cornachio said Brown was tapped during the grand jury deliberations that resulted in the indictment of Holley on a single second-degree-murder charge.

"We've had limited applications that we've had to make, but any time that we have approached him with any kind of a grand jury application, they're very cooperative," Cornachio said before the indictment was handed up on Jan. 29. "I haven't had any issues with them at all."

Reach Peter D. Kramer at pkramer@gannett.com. Support this kind of journalism by subscribing, at subscribe.lohud.com.

This article originally appeared on Rockland/Westchester Journal News: Megan McDonald murder: Did judge cross a line by calling police?