Julián Castro honors Willie Velasquez's 'transformative' activism in Texas Monthly tribute

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

I've been reading Texas Monthly — not always religiously — since February 1973.

How could I not? The magazine applied some of the best reporting and writing in the country to a subject already dear to my heart, my home state.

Through the years, I've been fortunate enough to brush elbows with a few of the people who made the magazine into a national treasure.

Some of its first writers and editors, such as Bill Broyles and Gregory Curtis, studied creative writing at Rice University down the street from where I grew up in Houston's West University. We lived just a few blocks from the house where their teacher, Larry McMurtry, and another of his former students, Mike Evans, stayed on Quenby Street.

No, I did not bump into them while riding my bike through nearby Southampton or at the Village shopping center.

To tell the truth, I first learned of their neighborhood proximity in the aftermath of a visit to Quenby Street by countercultural ringmaster Ken Kesey and his "Merry Pranksters," as recorded in Tom Wolfe's 1968 book, "The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test," required underground reading at my high school.

Other encounters with TM history have been more direct. Two of Texas Monthly's current editors, Kathy Blackwell and Jeff Salamon, once shaped my work at the American-Statesman. The names of TM writers, such as Sarah Bird, Stephen Harrigan, Skip Hollandsworth and Nate Blakeslee, pop up fairly often in this column.

More: This Austin vintage cowboy boots hunter keeps Texas history alive with hundreds of finds

By now, you have figured out that Texas Monthly turned 50 this year. The magazine, always adept at promoting the state, warts and all, has not been shy about reminding the reading public of its anniversary.

In 2024, once the party is over, I'll reserve a spot on my Texas bookshelves for this reminder of the magazine's consistent high quality and cultural insight: a handy birthday volume, "Lone Stars Rising." It compiles the magazine's profiles of leading Texans over the course of five decades. Some of the essays were written for this book, others were retrieved from TM's archives.

The subtitle, conveyed with TM's usual brash flourish, gives away the game: "The Fifty People Who Turned Texas into the Fastest-Growing, Most Exciting, and, Sometimes, Most Exasperating State in the Country."

It would be a fool's errand to list all the profiled luminaries here.

Instead, I received an OK from project director Salamon and his team to republish a piece about the only Texan on the list who was previously unfamiliar to me: San Antonio community activist Willie Velasquez, as remembered by Julián Castro, former U.S. secretary of Housing and Urban Development.

Velasquez's story of political service, stamina and resilience reminds me of those of the civil rights leaders who changed Austin for the better, and whose lives have been recorded in the pages of this newspaper.

A tribute to Willie Velasquez from Texas Monthly

Here is the intro from the book followed by Castro's profile:

Willie Velasquez was the son of a San Antonio union organizer, and it was clear from early on that he would follow in his father’s footsteps. After graduating from St. Mary’s University with a degree in economics, Velasquez immediately dived into activism, working as a boycott coordinator for the United Farm Workers in the Rio Grande Valley.

He was deeply involved in the famous Starr County Strike of 1966 and 1967, a series of actions conducted by underpaid workers in the valley’s melon farms. The strike, which was marked by law enforcement abuses, failed in its efforts, despite drawing national attention to the workers’ plight.

Velasquez, though, soon pivoted to a more successful strategy: empowering Latinos by registering them to vote in large numbers. By the time of his death in 1988 at the too-young age of 44, he was widely regarded as one of the nation’s most transformative civil rights activists.

Julián Castro on Willie Velasquez

Growing up as the child of a Chicana activist in San Antonio’s West Side in the 1980s, whenever I heard someone refer to “Willie,” I didn’t picture a long-haired, pot-smoking country singer strumming on his guitar.

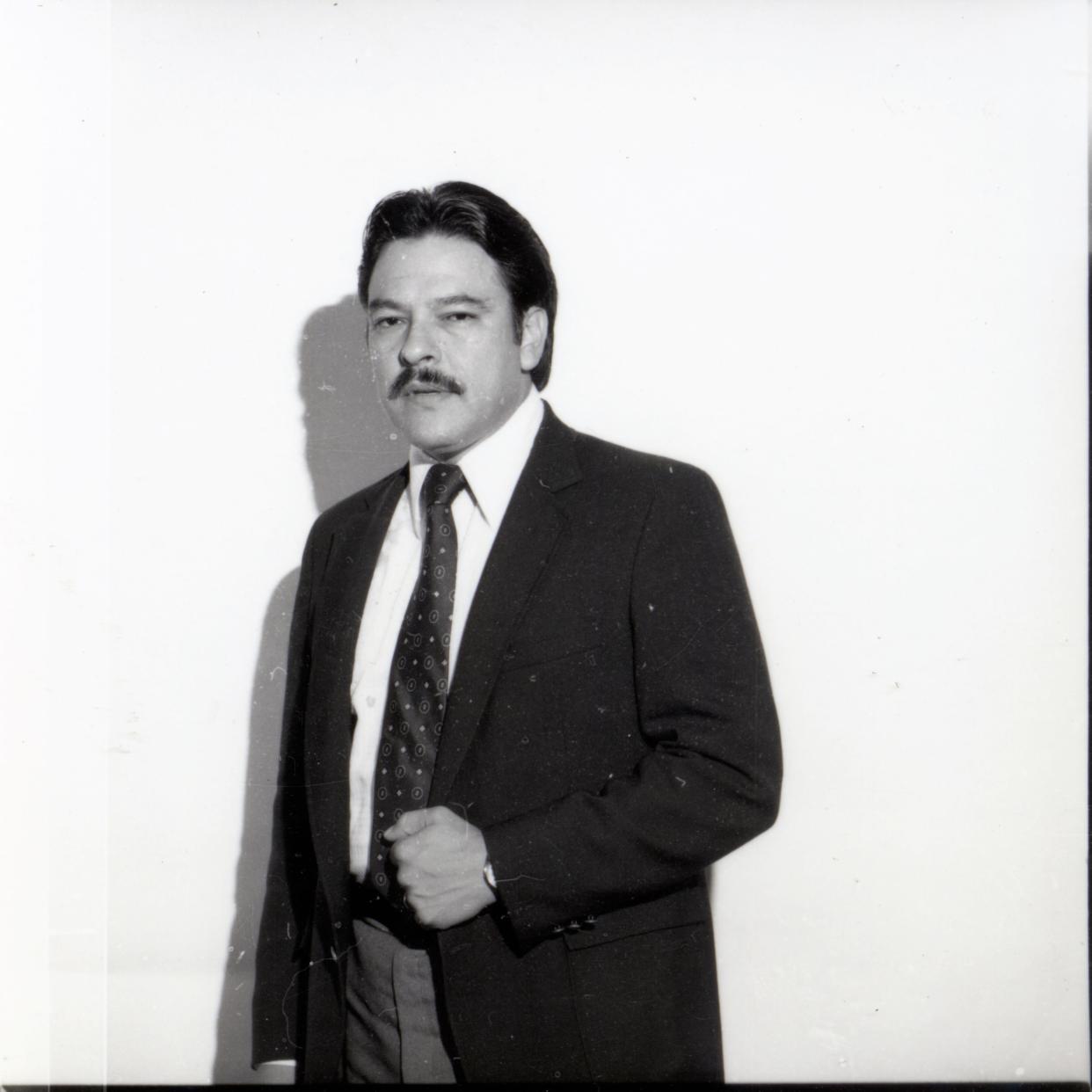

“Willie” instead called up a stout, raven-haired and jabby-voiced political activist walking door-to-door with pen and pad in hand, a man on a mission to empower Mexican Americans by registering them to vote.

“Willie” meant Willie Velasquez, the visionary founder of the Southwest Voter Registration Education Project, who was also a product of the West Side.

More: A generation of Black and Hispanic civil rights pioneers left Austin a better place

The post–World War II San Antonio that Willie grew up in offered little upward mobility for Mexican Americans. High dropout rates, stifling poverty and prejudice suffocated the community.

In 1968, the CBS documentary "Hunger in America" spotlighted San Antonio’s West Side, capturing one of the most heart-wrenching moments of film ever broadcast on television. In a San Antonio emergency room, a neo-natal physician cradled a tiny, emaciated brown-skinned baby as the child gasped his final breath.

“He was an American,” the show’s host, a young Charles Kuralt, intoned as the baby’s body went limp on the screen. “Now he is dead.” One-quarter of San Antonio’s 400,000 Mexican Americans “are hungry all the time,” Kuralt reported.

Even though Mexican Americans made up nearly half the city’s population, political power rested almost entirely in the hands of a white, business-friendly elite.

By the early 1970s, however, things had begun to change. The Voting Rights Act of 1965 had boosted voter protections for people of color. The Supreme Court had struck down the poll tax as discriminatory a year later, effectively ending a tool of disenfranchisement that Texas had wielded against minorities and the poor since the turn of the century.

More: 'Let's try to fix it together': Gonzalo Barrientos on civil rights, passing laws and helping people

By 1970, the Chicano Movement was blossoming in Texas. La Raza Unida, an offshoot of the Mexican-American Youth Organization, which Willie had co-founded in 1967 in San Antonio, was fielding candidates for local and statewide office.

Although Willie left La Raza Unida because he didn’t believe a third party was the best route to Latino political empowerment, he understood its potential to galvanize the Mexican American vote. When Ramsey Muñiz, La Raza’s candidate for governor, unexpectedly pulled 6 percent of the general election vote in 1972, he siphoned enough votes from Democrat Dolph Briscoe to scare the bejeezus out of the state’s Democratic establishment.

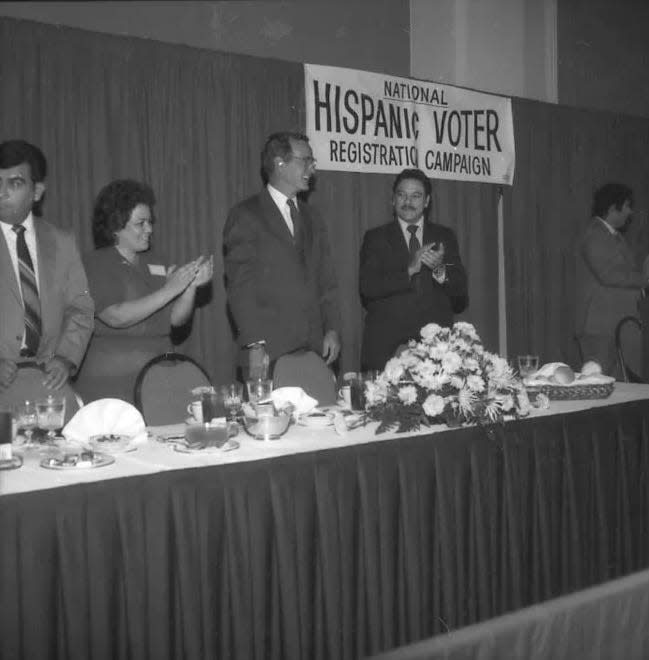

Willie understood the enormous power Latinos could wield to improve their lives if they turned out to vote. His genius was that he knew exactly how to make that happen. He formed Southwest Voter in 1974 with the purpose of registering Latino voters and educating them about the democratic process.

His vision was groundbreaking. It just wasn’t being done — not in Texas and certainly not in the Latino community — with the skill, scale, or fervor that Southwest Voter brought to it.

More: Richard Moya, first Mexican-American Travis County officeholder, dies

Person by person, family by family, neighborhood by neighborhood, the group helped nearly double Latino registration nationwide over the course of two decades. More Latino voters also meant more Latino candidates elected to office. In the five Southwestern states where it focused its efforts, the number of Latino elected officials jumped from 1,566 in 1974 to 2,861 in 1984.

“¡Su voto es su voz!” — “Your vote is your voice!” — was Willie’s exhortation to Latino voters.

Every time I hear it, I get a lump in my throat thinking of the generations of Latinos and Latinas who never had the opportunity to fully use their voice, either at the ballot box or in life. They labored in fields and factories, in homes as maids and gardeners, in faraway lands fighting for our country. They worked hard and often stayed quiet about the injustices around them at the risk of losing their job if they rocked the boat.

Willie changed the game.

More: Make sure Roy Guerrero is remembered not just as a park

I remember overhearing my mom talk about Willie with her activist friends at Panchito’s, a basement restaurant in the Plaza de Armas Building, where she worked in the city’s personnel office in the mid-1980s. It wasn’t uncommon for her to breathe fire, as activists are sometimes wont to do, at people she thought were hyped-up but ineffective.

But she saw Willie as the complete opposite: “He gets it,” she told them, her declarative words delivered in a tone of respect that she reserved for people she believed were making a difference, “and he’s getting things done.”

“What you are seeing is a transition from powerlessness to power,” Willie declared to an audience at Harvard’s Institute of Politics in March 1988, only three months before his sudden passing from cancer at age 44.

He was right. The movement he started helped transform American politics. Today, Latinos are one of America’s most sought-after voting blocs, with Democrats and Republicans routinely competing for their vote.

More: East Austin community leader Johnny Limón has died at age 69

Perhaps most importantly, the sons and daughters of those who stayed quiet are using their voices not only at the ballot box but in courtrooms as attorneys, in clinics as physicians, in classrooms as teachers, and in city halls, in state legislatures, and on Capitol Hill in numbers thought impossible when Willie launched Southwest Voter almost a half century ago.

In 1981, San Antonio elected its first Latino mayor in a century, Henry Cisneros, and between 1970 and 2010 the poverty rate for Hispanics in Texas dropped from 40 percent to 27 percent.

The transition that Willie spoke of is far from complete. Too many Latinos are still cut off from the ability to reach their dreams. The Latino community still votes at lower rates than most others and Latinos hold just a quarter of the seats in the state legislature, despite accounting for almost 40 percent of the population.

In an age of election denialism, rampant disinformation, revived voter suppression and extreme polarization, Willie’s zealous faith in the democratic process should serve as a North Star. Coming from such a marginalized community, he had every reason to doubt that working within our flawed democratic system was the answer. But instead of throwing stones or storming the Capitol or trying to overturn an election, he put his faith in our Constitution’s highest ideals.

“‘Willie’ was and is now a name synonymous with democracy in America,” President Bill Clinton proclaimed as he posthumously bestowed on Willie the Medal of Freedom in a 1995 White House ceremony.

More: 'They broke down the barriers': Latinitas honors trailblazing women of color with mosaic portraits

Willie is one of the few Latinos ever recognized with the nation’s highest civilian honor. He made a difference, and the powerless and the powerful have long known it, whether they reside in the West Side or the West Wing.

Michael Barnes writes about the people, places, culture and history of Austin and Texas. He can be reached at mbarnes@gannett.com. Sign up for the free weekly digital newsletter, Think, Texas, at statesman.com/newsletters, or at the newsletters page of your USA Today Network paper.

This article originally appeared on Austin American-Statesman: 'Lone Stars Rising' collects 50 Texas Monthly notable profiles