As July 4th approaches, remembering a grand experiment based on 'consensus and compromise'

"We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their creator with certain unalienable rights, that among these are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness." — Declaration of Independence, 1776

Was a more succinct, stirring assertion of freedom ever written?

Yet U.S. history is rife with contradiction. “All men are created equal” was penned in the midst of legally sanctioned human bondage. The courageous settling of America and its expansion westward lived alongside the unpleasant reality of the slaughter of indigenous peoples who were in the way. And the 13th, 14th and 15th amendments to the Constitution guaranteeing freedom, equality before the law and voting rights to former slaves were largely negated by a series of state-sponsored Jim Crow laws.

Such contradictions flow throughout the American story. Ignoring them or pretending they don’t exist or – worse – mandating that they not be taught hardly seems a path to better understand our fellow citizens and the history of how we got to the present day. Acknowledging reality would appear basic to any sort of self-improvement program – and if America is anything, it is a rocky but real self-improvement project quite unlike anything in recorded history.

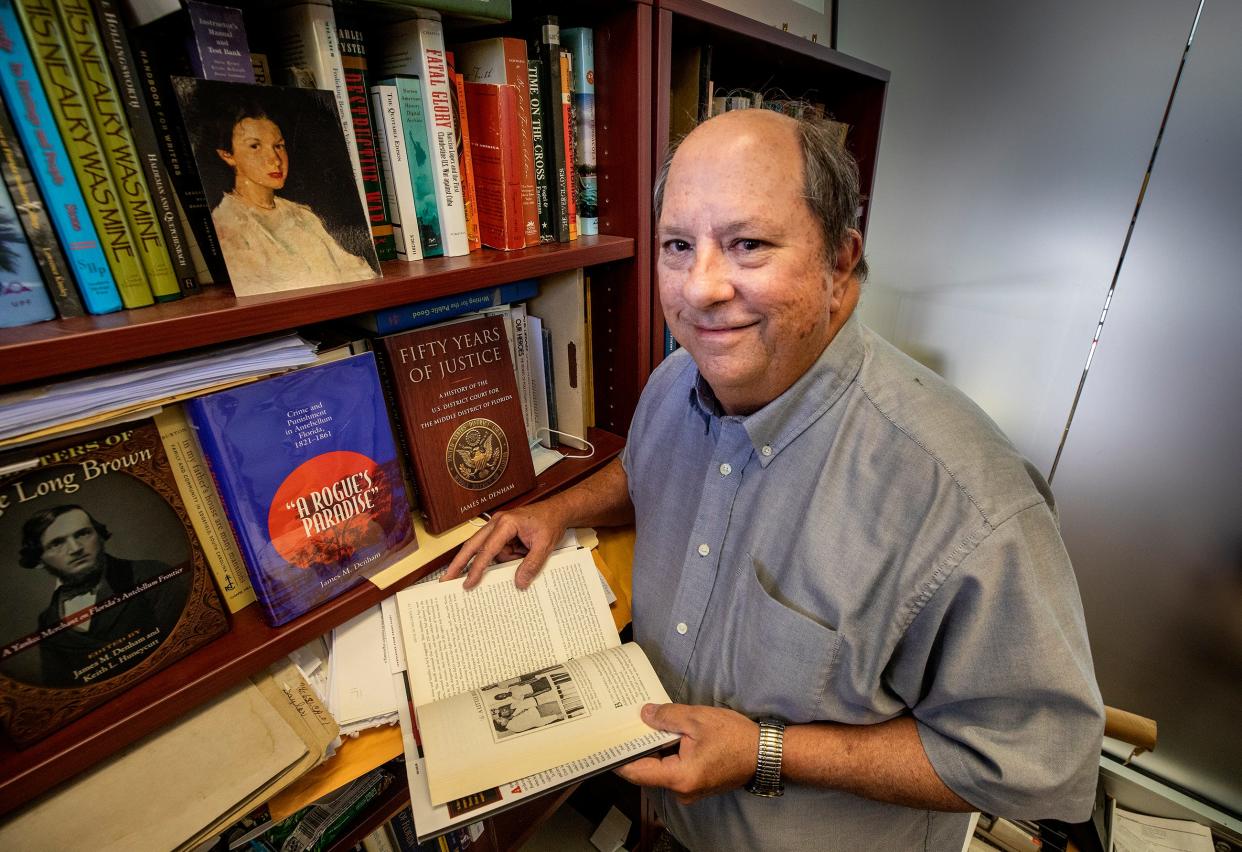

James “Mike” Denham is professor of history and director of the Lawton M. Chiles Jr. Center at Florida Southern College, where he has taught since 1991. Denham, 66, previously was an instructor at Florida State University and Georgia Southern University and has held fellowships at West Point, Harvard and Columbia, among other institutions.

Q. Many signers of the Declaration of Independence and delegates to the Constitutional Convention as well as four of the first five presidents were slave owners. They were certainly not unaware of the paradox. George Washington himself, while asserting the need for independence from England, wrote to a friend that its absence “will make us as tame, and abject slaves, as the blacks we rule over with such arbitrary sway.” How does one square the inspirational ideals expressed by our forebearers – the very real risks they took and the sterling documents they created – with the reality of widespread slave ownership?

A. It is the great stain of American history. It’s the most perplexing, unanswerable question that someone like Thomas Jefferson or Patrick Henry would be a slaveholder. The only way to explain it is the context of the time, the world these people grew up in – the fact that the Royal African Company was supplying Africans to the American colonies, as many as they could acquire, the tremendous amount of land available for settlement and, most unfortunately, the belief or at least the acceptance as fact that these people were inferior and were made for this, that they were trading one civilization for another – Africa being a land where buying and selling human beings had been a common thing. Land was money. Slaves were money. The Europeans and then Americans made this into an industry. Slavery was literally the most lucrative enterprise in the world at the time.

Q. Domestically, the war of independence from England was a much messier and more convoluted affair than is commonly recognized, with many colonists supporting the mother country. What are some of the myths about the war and some of the less well-known but highly salient aspects of that revolution?

A. One of the things we forget about the American Revolution is that it lasted seven years – seven years! What was the conflict between the patriots and the loyalists like? It was a bloodbath. The worst atrocities were committed – killing, burning villages, rape and plunder – and it was like that because it was really a civil war, Americans versus Americans. John Adams said that in America during that time we were cut into thirds – a third strongly supported the revolution, a third strongly opposed it and a third were just trying to get away from everything and didn’t care.

'My childhood friends' Winter Haven grads, Army officers died in Vietnam17 months apart

Despite sad memories Lakeland Green Beret Kenneth Conklin 'would do it all again'

A salute to military veterans 'Honor the service of those sons and daughters' who sacrificed

There’s this myth that all the loyalists were rich, fat cats – mean spirited, totally denigrating the poor, hardworking patriots who were suppressed by them. Nothing is further from the truth. Like any period in history, it’s tremendously complicated. There were rich loyalists and poor loyalists. John Hancock was one of the richest men in the colonies. He found it not only in his spirit but also in his best interest to join the patriots’ side. There were many people in the back country who took a loyalty oath to England to get land or other goodies. Some were loyalists because the people they hated in their villages were patriots. And many animosities were brought over from their mother countries. So it’s very difficult to generalize.

Q. What factors might have altered the outcome in favor of the British?

A. There were tipping points throughout the entire conflict and particularly in the beginning. In the first couple of campaigns Washington’s army was just waxed, run out of Long Island – barely escaped and nearly destroyed. If not for fate or bad weather it might have been a very short revolution.

The other thing about the war was its international aspect. This was also very much a world war. We talk of the First and Second world wars but they were more like the seventh and eighth world wars. The American revolution involved France, Spain, Holland, the League of Armed Neutrality – a coalition of Baltic powers – all of whom ganged up on Britain because it had become so powerful. They saw it in their own best interest to support, indirectly if not directly, the Americans. By the end of the war, England was getting it from all sides. And the British public had had it – seven years, all that money, all that blood and treasure – so they made peace.

Q. A journal kept by one of the delegates to the Constitutional Convention records that when Benjamin Franklin was asked, “What have we got – a republic or a monarchy?” he replied, “A republic – if you can keep it.” We’ve managed to keep it so far, but in your estimation are fatal cracks starting to appear, as evidenced by widespread election denial, attacks on the Capitol and retreats into political silos that merely confirm whatever biases we already harbor?

A. Our country is based not just on e pluribus unum – out of many, one – but also on consensus and compromise, and the idea from the very beginning that nobody gets everything they want. Unfortunately, in our hypersensitive information age, everybody has access to constant information and the people who are giving it out have economic motives in dividing people and making people angry. Nobody can agree on facts anymore. Nobody wants to compromise. One of my favorite phrases is “don’t let the perfect be the enemy of the good.” I guess we all strive for perfection, but our own notion of perfection may be something that is very different from another person’s.

Our country is also based on people having a common notion of what facts are, of being connected in a civil way, of having an understanding that representative democracy really is a good thing. Sometimes I wonder whether some people are willing to junk that idea. In a democracy, nobody gets everything they want. But some people seem determined to have it their way and are willing to do anything to get it.

Q. There’s never been a revolution in history in which “the pursuit of happiness” was a stated objective. In these times of harsh partisanship and inability to agree on basic facts, are Americans becoming less happy with who we are as a people and as a nation? Does e pluribus unum still hold?

A. That was the most brilliant phrase that’s ever been written – the pursuit of happiness. Unfortunately, we have descended into a period where there are vast numbers of people who think the only good pursuit of happiness is their own pursuit, and every other type of happiness ought to be banned. I’m not talking about the most egregious kind of behavior that no one supports. But there are people trying to ban not only the pursuit of happiness but of thinking a certain way, writing a certain way, learning a certain way – because it doesn’t conform to their own specific notion of what is right and wrong.

Q. We have always been a nation of immigrants. At the time of the revolution, much of the population were either immigrants or children thereof. Today in Florida about a fifth of the population still speak Spanish. Six percent identify as Asian. One in five was born in another country. We are a very diverse state. What strengths do immigrants bring and why do many consider immigration and diversity a mortal threat?

A. They consider it a threat because of the striking disparities of their race, their ethnicity, of their beliefs, of their religion – and that’s always been the case. It rises and falls based on a lot of different factors, including economics. Most immigrants come with tremendous ambition. They’re young, energetic, they work incredibly hard – in construction, picking crops, washing dishes. In large part, they’re after the American dream – to be independent and to pursue their own happiness.

But many want to close the borders entirely – and that’s not something new. It goes back to the colonial period and the mass migration of the late 19th century. I think it’s always going to be with us. With the 24-hour news cycle, people get ginned up. One person commits a heinous crime and the whole group gets cast with aspersions. Some people in our government don’t want to solve it because it’s a very compelling political argument if you can frame the other side negatively. Both sides are guilty and there are those who are simply determined not to deal with this problem.

Q. There is a movement afoot in Florida and elsewhere to ban books, sanitize the past so that no student feels “uncomfortable,” prohibit the teaching of certain subjects and to literally rewrite history. What consequences, directly or indirectly, flow from such actions to censor history, deny access to reading materials and in general quell dissenting viewpoints?

A. The first thing that totalitarian countries do is control an understanding of the past. Censorship and dictating what people can or cannot freely enquire about is one of the greatest tools of autocracies. The fact that a government, a governor, a legislature, a president can ban a book is just reprehensible. What seems to be going on is a solution in search of a problem. Or at least an open attack to garner animosity for cheap political gain. It’s very disturbing.

We all talk about slippery slopes – you read "Catcher in the Rye" and the next thing you know you’re going to be a homosexual or a communist or whatever. To me the real slippery slope is this banning of books and trying to dictate what teachers or professors or scholars who have dedicated their lives to seeking truth get to say, do or write. Tolerance of disagreeable ideas is the price we pay for a free society.

Q. For all our problems, there is no doubt that this country has come a long way in overcoming adversity and prejudice. Many people and many nations have made the mistake of counting us out as a country, so as we celebrate Independence Day, what thoughts would you like to share with our readers about the country’s prospects?

A. To a certain degree, we’re always going to have this problem and it might even get worse. But I think we need to go into this with the idea that we have to make our own peace with things we may not like, that we have to understand that we’re not – or our group or organization or political party is not – all-knowing and has all the answers and should have total control over the country. And if we don’t, the whole world’s going to come to an end. We have to understand that we live in a diverse society and that our experiment will not last if we descend into squabbling factions or groups.

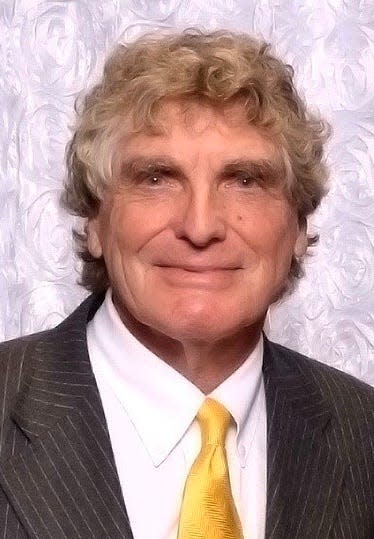

Thomas R. Oldt can be reached at tom@troldt.com.

This article originally appeared on The Ledger: On July 4th, Florida Southern professor reflects on changing nation