A Jungle Walk on Tiger Safari is an Emotional Roller Coaster

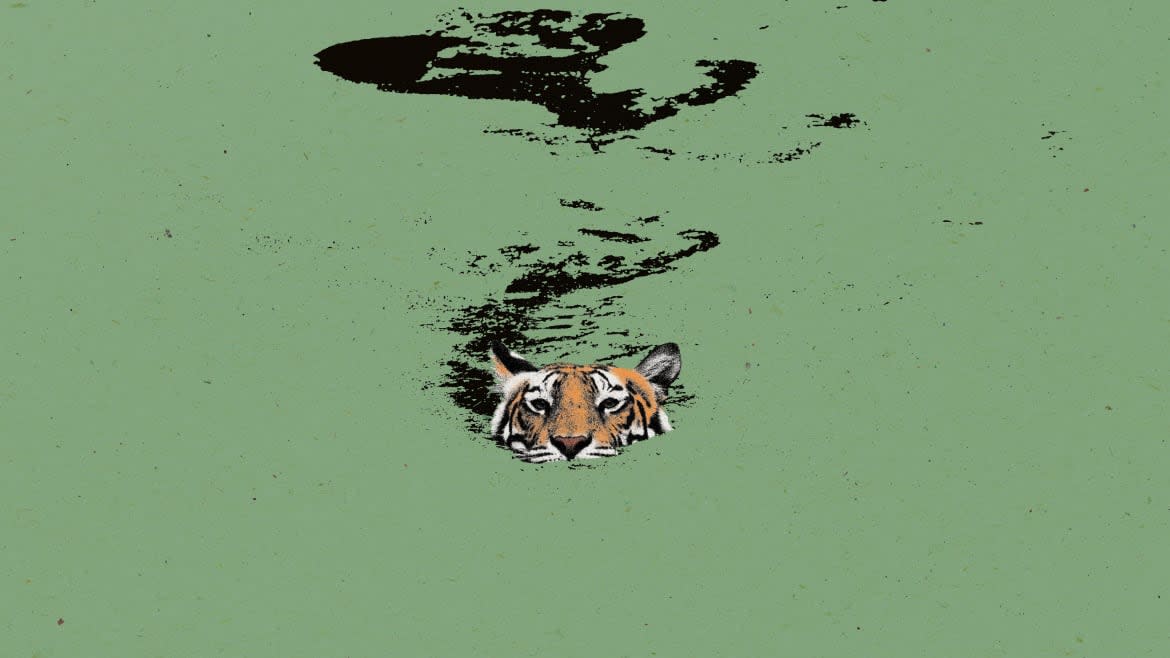

Chinmay Deshpande pointed to a patch of wet brown earth. “See that?” said the naturalist with Pugdundee Safaris. He kneeled down to get a better look, and sniffed. The damp spot was urine from a tiger. He had peed right where we stood, on a leafy remote trail in India’s Satpura National Park, perhaps not an hour before. As for specifics, the tiger was almost certainly male because of his massive footprints, which were the size of dinner plates.

Judging by its fresh urine, the stealthy predator was probably still around, close by in the dense sal and teak forest.

Depending on your perspective, this was either fantastic—we might see a tiger in the wild as we crept in the jungle, as opposed to the usual perch of an open-air jeep.

Or terrifying—we might encounter a tiger in the wild.

At that point, Deshpande, a slight man of 28 with glasses and a wide smile, used the occasion to dispel a myth. “There is no such thing as a man-eating tiger,” he said, launching into a talk on the pressures on tiger conservation.

Before I ventured to the hilly grasslands and fabled forests of Madhya Pradesh, India’s wild heart, I’d read some wild stories about human-animal conflict outside its tiger reserves. Landlocked, and set in the heart of Central India, Madhya Pradesh is the subcontinent’s largest state. Tigers need lots of territory to migrate and mate, but they’ve lost 40 percent of their habitat over the last decade because of development. Illegal hunting has also reduced their prey, driving them closer to villages. Usually these stories of conflict involved a farmer who’d been mauled or killed by a tiger hunting for easy prey like cattle—not humans.

That sunlit morning in Satpura, as we hiked back to our civilized tent camp on the Denwa River, we saw a cow carcass in the shadows of the trees, its abdomen shredded and its guts spilling out. We didn’t linger to see if the tiger would return to retrieve his kill. But in India, the effort to protect the country’s beautiful Bengal tiger remained fraught with politics.

During the last century, India’s tigers were nearly wiped out because of demand for their gorgeous striped skins. In 1973, after the government of Indira Gandhi banned hunting the iconic animals, a national movement to create tiger reserves and preserve their territory flourished. Villagers were compensated for their land and moved to other areas where they could farm, or offered jobs in the parks. Those conservation efforts worked.

Today, India is home to more than half the world’s estimated 4000 tigers, spread across 50 dedicated tiger reserves. Since 2014, the tiger population in the country has grown from 1,400 to 2,977. Much of this success is due to the efforts of 300 wildlife tour operators, including Pugdundee Safaris and Royal Expeditions, which belong to TOFT, an organization committed to using nature tourism to protect the endangered tigers and their habitats.

The night before I went on safari in Pench National Park, one of the world’s largest tiger habitats, I lay awake in the dark. It wasn’t simply because I was excited. I was sleeping in a treehouse, wrapped around a sturdy Mahua tree. Scratching noises, thumps and cries rattled the roof. Were those macaques leaping around just above my head? I wondered. Vipers slithering in the leaves and elephant grasses?

It was still dark and cold when our jeeps left Pench Tree Lodge, and rolled out into the countryside. As the sky lightened, we swept past wide green fields, and platforms in trees where farmers slept to guard their livestock from predators. I spotted my first wild animal: a shaggy black boar trotting along the road. But would I see a wild tiger in Pench? Although 53 of the endangered animals roamed the park and its buffer areas, they were stubbornly elusive. “The moment you’re watching them, they disappear,” Deshpande had said.

For three hours, we bounced along a winding dirt road, trailing about a half dozen other jeeps. Dust flew, blanketed our faces. I coughed, sipped from my water bottle. As we moved, cameras to capture tiger images to monitor the population clicked overhead. Perched in the rear seat, I peered into the straw-colored grasses, the tall teak trees, looking for a flash of saffron, thick black double stripes. Only a certain number of jeeps were allowed at a time in the park to avoid congestion, tracked by GPS. Guides weren’t allowed cell phones, either, so they communicated by walkie-talkie. Every so often, our naturalist would alert the driver, point in the hazy distance. Someone had seen something. We’d slam to a halt, waiting, the songs of 150 species of birds surrounding us.

I saw many wonderful animals. A troop of silver lemurs who were squatting on the ground, grooming each other’s fur, while samba deer grazed placidly nearby. A tiny gray owl tucked in a hole high in a gray tree. At one point, a jackal loped along the road ahead of us. I saw a beautiful solitary spotted deer in a stand of forest. And although others in our group returned to the lodge that afternoon bursting with tiger stories, I did not.

Outfitted with a hot water bottle and wool blanket against the chilly dawn, the next day I rode with a delightful young guide named Himani Singh Chouhan. Chouhan, who had a bright smile and brown eyes, was from the northern state of Rajasthan. She was planning to be a doctor but changed her mind because her true love was wildlife. One of the few female naturalists in the national parks, she was as rare as a leopard sighting.

At one point, the driver shifted into low, cut the engine. Had he heard a tiger call? Chouhan asked. No, but around 4:00 that morning, forest guards patrolling the area for poachers had heard a tigress roaring. They’d also spotted her with her four cubs. A little while later, Chouhan pointed out some tiger and leopard paw prints on the ground as we idled. I was elated.

Then she told us of her own brush with a leopard. She was walking with a few colleagues in a sanctuary in Rajasthan when they spotted blood on the ground. They got excited, and decided to track the blood. A guide was in the front, she was behind him. After a mile or so they came to a river below a hillock. Should they cross and climb the hill to get a better view? they debated. “We are going!” Chouhan announced. The guide took a step, and that’s when they heard a “big” growl. “The leopard was sitting right in front of us, watching us. With a monkey kill,” she said. The guide was so terrified he darted to the back of the group. And the leopard ran into the brush carrying its next meal.

I noted that she was lucky the angry cat took off. “Oh, yes,” Chouhan said, laughing. “If I had been alone there I am gone. When you try to chase them with their kill, they will try to attack you. That’s how all the conflicts happen in India. It’s not the tiger or the leopard or the sloth bear’s fault.”

I kept this in mind a day later when I was in Satpura, and we spotted a sloth bear off in the forest—or at least his black furry back. Sloth sightings are rare, and we almost missed him. His entire head was buried in a termite hole, his long sharp claws digging. When he emerged, presumably sated, we watched breathlessly as he waddled behind our jeep and across the road. He was cute, sort of. “When you know that the sloth bear is coming, you should not go closer to him. And if you do, bad luck for you,” Chouhan had told me.

I never did see a tiger while I was in India. But I can live with that. The day I rode in Pench National Park with Chouhan, we saw a creature even more elusive: a leopard. He was calmly sauntering ahead of us on the road. He was stunning.

Get our top stories in your inbox every day. Sign up now!

Daily Beast Membership: Beast Inside goes deeper on the stories that matter to you. Learn more.