The Junkyard as Seen in Infrared Light

With all the old-time photographic equipment I use to document car graveyards, it seems inevitable that I'd need to see what happens with those cameras loaded with film sensitive to the same not-visible-to-human-eyes light wavelengths that have expanded our understanding of the supermassive black hole at the center of our galaxy. That's right, you can still get infrared-sensitive film from Rollei, and so I picked up an assortment of IR filters and used high-tech fabrication skills to attach them to a quartet of cameras made from 1910 through 1976.

Because one of my new IR filters screwed right onto the lens of my reliable Canon AE-1 35mm SLR, I decided to shoot a test roll of the much-photographed 1953 Ford F-100 in south Denver. If you shoot infrared film with no filter, it just behaves like regular film…

…but with an IR filter—in this case one that blocks out light with wavelengths shorter than 760 nanometers, much redder than the human eye can see—you get a dark sky and light vegetation, plus a generally weird appearance that worked well for 1960s psychedelic album covers.

That worked pretty well, so my next step was to load some 120 infrared film into my Vredeborch Vrede Box, a postwar German box camera that's very well-made. To mount the 720nm infrared filter on its flat face, I used black masking tape. Why not?

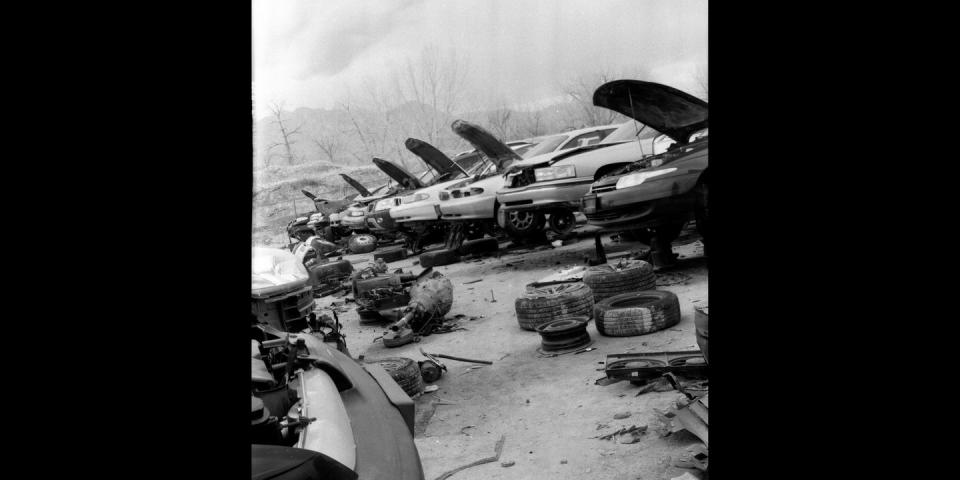

Bringing it to the Denver yard with the '76 Checker Taxicab, it captured some otherworldly photos of the Automotive Grim Reaper's waiting room.

Using the same filter-mounting technique to render a 1919 Kodak No. 2 Brownie Model E infrared-ready, I headed to Colorado Springs in hopes of getting some dramatic boneyard shots with Pikes Peak as a backdrop.

Unfortunately, a windy April snowstorm was rolling in at the time and the air was too full of moisture and dust to get a good infrared effect.

I'd gotten some interesting effects with color film loaded into a 1910 Kodak No. 2A Folding Pocket Brownie modified with a pinhole lens, so I decided to try infrared film and an IR filter on the same camera. Here it is propped against a junkyard decklid for a three-minute junkyard exposure.

It turns out that a pinhole camera shooting through an infrared filter needs much longer exposures than I expected, so I'll need to try again to get better infrared TR7 Victory Edition shots. For now, here's the gallery with sets of infrared photos from all three ancient cameras: