‘I just cried’: When restrictions kept Black people out of Wake County neighborhoods.

In a 1914 sales brochure for a house in Raleigh’s former Cameron Park neighborhood, developers appeal to upper middle-class white residents eager to leave the more racially mixed downtown, boasting housing restrictions that “properly safeguard” their interests.

“Premises shall not be occupied by negroes or persons of negro blend,” one passage states, except if the person is “employed for domestic purposes.”

The next line restricts “pigs and hogs,” adding further insult.

It’s a cruel reminder of the county’s racist past. Today’s residents have renamed their neighborhood Forest Park, cutting ties with its slave-owning namesake.

But it’s also a truth that leaders and amateur historians want people to remember.

The brochure is now part of a growing collection being archived under a new Wake County Register of Deeds initiative called the Racially Restrictive Covenants Project.

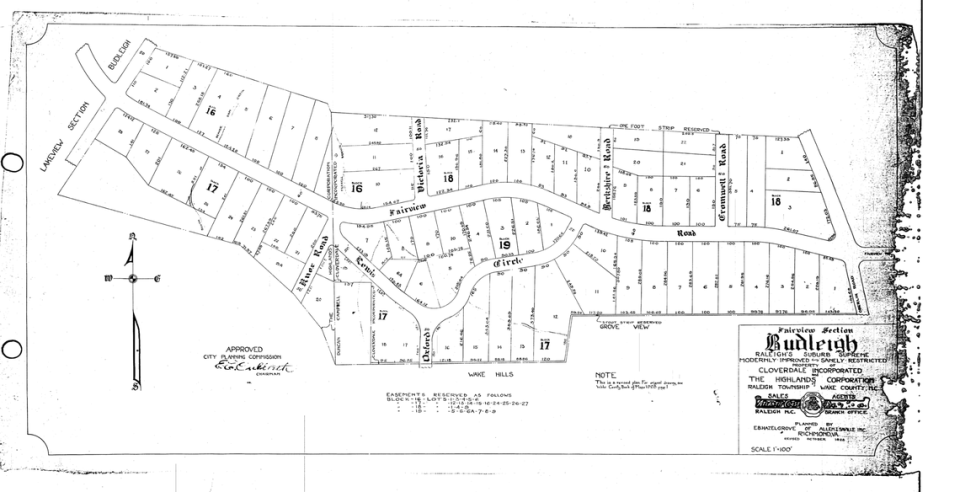

Organizers plan to create a searchable and interactive map of historic racial restrictions that once prevented people from buying or living on land in Wake County.

“Sadly, these racially restrictive covenants can be found on the books in nearly every county and city,” said Register of Deeds Tammy Brunner. “Wake County is not unique.”

Although the Supreme Court ruled these kinds of covenants unenforceable in 1948, and the passage of the 1968 Fair Housing Act outlawed them, the painful, offensive language still exists in hundreds of deeds of homes, neighborhoods or cemeteries across the county, she said.

Most were written to keep Black people from moving into certain neighborhoods or to keep them from being buried in certain cemetery plots, but others may target ethnic or religious groups. In many cases, it resulted in nearly all-white neighborhoods for decades to come.

“A lot of people don’t know about them, and many are shocked when they learn their property or the neighborhood HOA where they live still includes such racial restrictions,” Brunner said.

Wanted: Armchair historians

Husband-and-wife team and long-time volunteers, Lisa Boccetti and Robert Williams, are leading the year-long effort, which launched last month. They’re now calling on volunteers to help dive into its archives: some hundreds of thousands of deeds from about 1920 through 1950 containing instruments, easements, and leases. To get involved, volunteers are asked to go to wake.gov/covenants and fill out the interest form.

Boccetti said they’re hoping to help people understand how the transfer and ownership of property “have shaped, and continue to shape our community.”

Though she can’t put a number on how many “hidden covenants” she expects to unearth, Boccetti predicts it will fluctuate from year to year.

“Post-World War II, during the boom years, we’ll expect to see more,” she said. “We’ll have to wait and see if our predictions are accurate.”

For Carol-Veronica Reeves, who has worked in the industry for nearly 25 years, it’s long overdue. As a Black Realtor, she still remembers the pain of a coming across her first restrictive covenant as part of a deal.

“At first, it didn’t sink in, then after a few minutes I just cried,” she recalled. “I was the only female agent with brown skin in that office. A sense of distrust sank in at the reality of how we were — and still are — viewed as non-human by some.”

Now running her own firm, The Reeves Team, out of Knightdale, she said it’s important to raise awareness “as uncomfortable as it may be for some.”

Enslaved Persons Project

This new project follows the Register’s Enslaved Persons Project, launched in 2021 with the help of Shaw University. That project served to unlock human stories of slavery through the register’s archives.

Volunteers helped to catalog, transcribe and make public the records from more than 30 deed books containing bills of sale and property exchanges for people. As enslaved people were not issued birth certificates or marriage certificates, property deeds and bills of sale were sometimes the only written records of the lives of these men, women and children.

Those records are now accessible and searchable in an online portal, allowing hundreds of people to track the history of their families at wake.gov/enslavedpersons.

On the Market

Keep up with the latest Triangle real estate news by subscribing to On the Market, The News & Observer's free weekly real estate newsletter. Look for it in your inbox every Thursday morning. Sign up here.