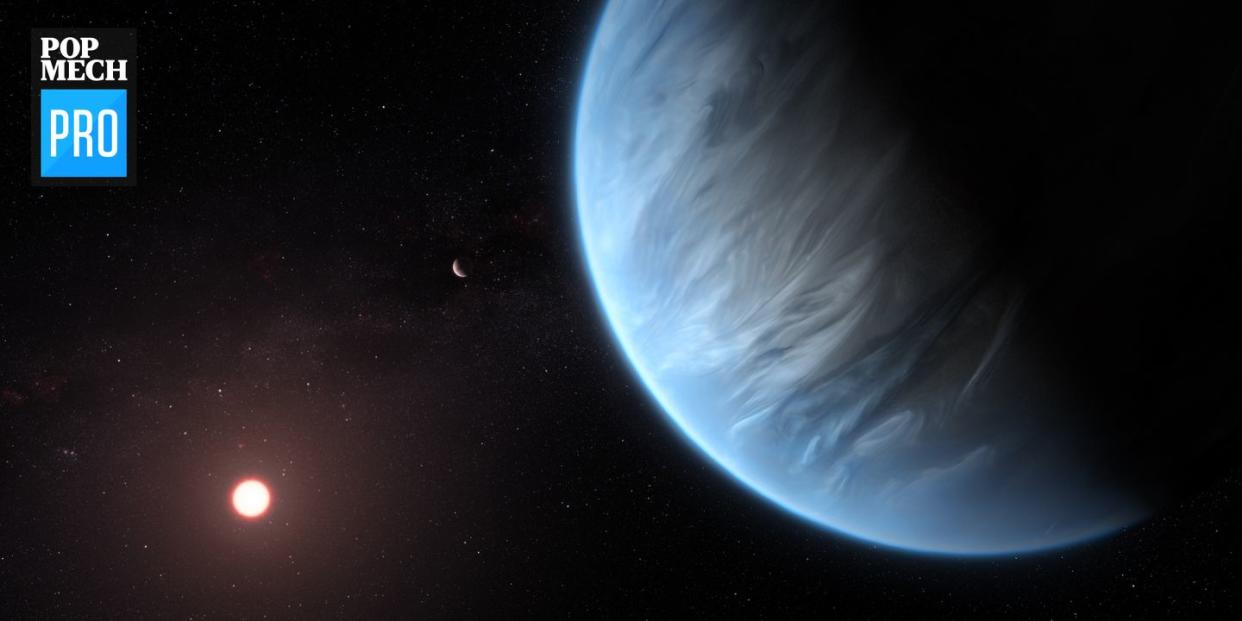

We Just Found Water Vapor in the Atmosphere of a Potentially Habitable Exoplanet

First, the good news: We've found water vapor in the atmosphere of a planet in the habitable zone of its star.

Now, the bad: That doesn't mean we've found a truly habitable planet yet. But it sure is a promising sign.

In a paper published today in Nature Astronomy, a University College London team reported the detection of water vapor in the atmosphere of K2-18b, a planet 110 lightyears away.

"This is the first detection of its kind, and in addition, this is a planet that’s orbiting in the habitable zone of its host star," said Angelos Tsiaras, one of the paper's authors and a research associate at University College London, in a press call in advance of the paper's publication.

The detections were made by the Hubble Space Telescope. The planet passed between its star and Earth on its 33-day orbital path around its star, allowing Hubble to see some of the gasses of its atmosphere.

But the planet isn't quite Earth-like: It's 2.2 times the radius of Earth, and is around 8 times its mass. That puts it near the upper limit of a type of planet called a super-Earth. Neptune, for instance, is about 17 Earth-mass and Uranus is around 14, which puts this planet closer to their mass than our own.

"K2-18 b is one of the potentially habitable planets in our Habitable Exoplanets Catalog, but not one of the top 21," Abel Mendez, director of the Planetary Habitability Laboratory at the University of Puerto Rico-Arecibo, tells Popular Mechanics. (Mendez was not involved in the study.)

"The habitability of this planet depends on its still-unknown bulk composition," says Mendez. "It could either be a rocky core with a super dense atmosphere, thus not habitable, or an ocean world marginally habitable. The presence of water vapor in its atmosphere is compatible with both scenarios."

K2-18 b appears to have a relatively cloud-free atmosphere, though aside from evidence of hydrogen and water vapor, the researchers aren't sure what other chemicals might be in the atmosphere because the detection was at the limits of Hubble's ability.

"The fact that we’re seeing clearly this water vapor signature means that even if there are clouds, there are clearly areas of transparency," says Giovanna Tinetti, a professor at UCL and author on the paper. This level of transparency could mean K2-18 b has Earth-like skies with a clear view of its parent star.

While Tsiaras called K2-18 b the "best candidate for habitability as we know it right now," that's a distinction that reflects more on the first-of-its-kind detection. There are planets we know of that are closer to Earth in size and in mass, including the planets of the TRAPPIST-1 system, which are all roughly between the size of Mars and Earth.

At least three planets in that system are within the habitable zone. Indeed, just one star system and 4.2 lightyears over, Proxima Centauri hosts a planet likely slightly larger and more massive than Earth in the habitable zone.

But what many of the more-Earth-size-and-mass planets lack is evidence of an atmosphere. Indeed, only three exoplanets of this class have had their atmospheres measured at all. Those other super-Earths were too hot to be considered habitable, and were large like K2-18b.

Right now, the basic problem is that this detection already strains what Hubble can do; trying to detect the atmospheres of smaller planets will require bigger telescopes. The James Webb Space Telescope, NASA's Hubble successor, will be better able to characterize small, rocky planets rather than just high-mass super-Earths.

However, the detection of the atmosphere around K2-18b is important for another reason. It orbits an M-dwarf star, the smallest and most numerous kind of star in the universe. They are more active than larger stars, often sending off extensive flares, especially early in their life. This could spell doom for their planets, as many models show the atmosphere being swept away by this stellar activity.

Thus, for many of the potentially habitable planets we know of, we're unsure if they have an atmosphere at all. The confirmation of an atmosphere around the hot planet GJ 1132b gave hints that it's possible for M-dwarf planets to retain their atmospheres, but the results published today are the first confirmation of a habitable zone planet around an M-dwarf maintaining its atmosphere.

"We observed the red dwarf star K2-18 multiple times from the Arecibo Observatory from 2017 to 2019," Mendez says. "There was no detection of quiescent or flares emissions during our observations." This may be why K2-18b was able to retain its atmosphere where others don't, which leaves the fate of planets around more active M-dwarfs more uncertain.

There are still plenty of unknowns regarding the actual habitability of K2-18b, but the detection of water vapor is an important first step in figuring out if similar worlds are habitable. Given its high gravity, it may not be the perfect planet—but it could make a pretty good testbed going forward for the larger observatories to come in the future.

You Might Also Like