‘Just help somebody.’ Fort Worth nonprofit meets needs of arriving Afghan refugee families

Angie Kraus pauses at the door of a south Fort Worth apartment and, according to Afghan custom, slips off her sandals. The living room is nearly devoid of furniture, and a baby girl is lying on a blanket near the kitchen.

“We want to see what you need,” Kraus says to young Afghan mother Aziza through an interpreter.

It’s Kraus’ first time to meet this family. She’s come prepared with an electric tea kettle and iron — necessities in every Afghan home.

Aziza already has a vacuum and a blender, she tells Kraus, but she needs a bed for the baby.

Kraus lets Aziza know about the English classes offered at the apartment complex. She holds the infant for a few minutes before leaving and promises to find a baby bed and possibly a stroller. Then she moves on to a nearby apartment where another family with small children lives.

Kraus, a former school administrator, started looking for the next thing when she retired in June 2020. She found it in August 2021 when she saw scenes on the news of the U.S. withdrawal from Afghanistan and subsequent Taliban takeover. She knew she wanted to help Afghan families.

Kraus completed a volunteer orientation with Refugee Services of Texas, a refugee resettlement agency that has since closed its doors due a budget shortfall. At first, her volunteer work was confined to donations. Then she was asked to pick up some arriving Afghans from the Dallas/Fort Worth International Airport.

“I met a family,” Kraus said. “That’s what really changed it for me.”

Kraus dropped the family off in south Fort Worth, nearly an hour from her home. She assumed that was their permanent location, but two days later she learned the refugee agency had moved the new arrivals into an apartment complex 10 minutes from her house.

“I was like, I’m going to teach them English,” Kraus said. “I’m a retired educator, so I’m equipped to do this job. I’m so thankful to God — this is my purpose. And then I met the neighbors and the next neighbors.”

Eventually, 29 refugee families moved into the apartment complex near Kraus’ home. In March 2022 she started the nonprofit organization Amshera to assist Afghan refugees in Fort Worth. Amshera means “sister” in the Dari language of Afghanistan.

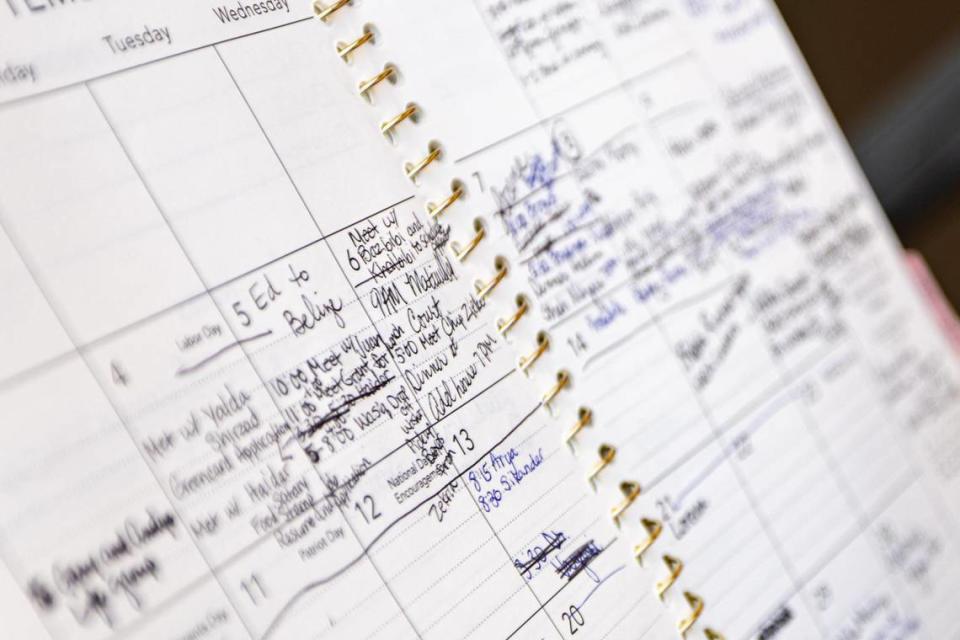

Today Kraus has about 170 families on her Google Sheets spreadsheet, and new names get added regularly. The calendar squares in her planner overflow with handwritten reminders to visit new families, take someone to a doctor appointment or help register newly-arrived children in school.

“We need more volunteers,” Kraus said. “Money would be great, too, but we need people. There’s not enough people serving all of them.”

A new home

On a Wednesday in late September, Kraus leaves her house early to pick up 62-year-old Mohammad Amini for a dental appointment. By 8:20 a.m. they are at Cornerstone Assistance Network, a nonprofit that offers free dental services, among other things, to uninsured Tarrant County residents.

Afterward, Kraus takes Amini back to his apartment and stays for a short visit with his family.

“I end up really here a lot,” Kraus said. “Like because I take him to an appointment and then they say every time I come ... ‘Angie, food!’”

Kraus met Amini and his family Jan. 3, 2022, the day they arrived in Fort Worth. Like the majority of Afghans admitted into the U.S. through Operation Allies Welcome, they underwent processing at a military base upon their arrival in the country.

According to Amini, they spent 72 days at a base in Indiana and 45 days at a temporary house in Saginaw before reaching their new home — a bare apartment in west Fort Worth. Resettlement agencies typically stock the apartments of new arrivals with basic necessities like dishes and cooking utensils, but Kraus said the Aminis’ apartment was empty.

Kraus was visiting another Afghan family at the same apartment complex the day Amini and his family moved in.

“He said, ‘We are here and we have nothing,’” Kraus remembers. “So we went to Walmart and we got blankets and food and silverware, and you know we just got everything that we could.”

More than a year-and-a-half later, the apartment is a far cry from that first day. Rugs, another necessity in Afghan homes, cover the floors. A sofa stands next to the front door and low cushions for seating line two walls of the living room. A U.S. flag and Afghan flag hang side-by-side on the wall.

While Amini’s wife serves flatbread and milk tea, Amini sits under the two flags and talks about his time in the Afghan Special Forces.

“I love USA,” he says through an interpreter.

Kraus makes more visits in the afternoon. At an apartment complex in south Fort Worth, an Afghan friend introduces her to Aziza and her baby.

A short walk across the parking lot and up a flight of stairs takes her to the apartment of another Afghan family with children. Kraus had heard the mother needed a playpen. A woman holding a baby answers the door.

No, she tells Kraus, she already has a playpen. What she needs is a baby swing. Kraus immediately sends her friend back to Aziza’s apartment with the playpen, which can also double as a crib. Then she moves on to her last visit of the day.

The Wahidis, a family of eight, arrived in the U.S. this summer. The younger children proudly show Kraus bright neon bandages on their arms — evidence of the vaccinations they received the previous day in preparation for starting school.

The oldest son is getting ready to apply for a job. Kraus tells him what the job involves and what kind work clothes he’ll need. She also praises his good attitude and willingness to learn new things.

“You will do great at that job,” she tells him.

Here, too, Kraus asks what the family needs and promises to bring them a sofa.

“We left all our things (in Afghanistan),” one of the sons said.

“This will not always be your house,” Kraus said. “Things will get better.”

A long road

Another obstacle Afghans fleeing the Taliban face in the U.S. is a backlogged immigration system.

Prior to August 2021, Zamir Khan was building a good life for his family in Afghanistan. Then the Taliban marched in, and Khan’s job of flying missions for the Afghan government that facilitated U.S. interests made him a target for the extremist organization.

D-Ray, Khan’s trainer and mentor, still remembers the conversation he had with Khan after the Taliban re-took control of the country. As a former instructor pilot with the U.S. military in Afghanistan, D-Ray asked his full name be withheld for security reasons.

“Do you want to leave?” D-Ray asked him.

“I’ll talk to my wife,” Khan replied. A few minutes later he returned to the phone. “Yes,” he told his friend. “They will kill me if I stay.”

With the help of a U.S. Congressman, D-Ray was able to get Khan, his wife and their two small children out of Afghanistan. A few months later the family settled in Fort Worth.

Khan said he’s thankful for the opportunities his children will have in the U.S. — opportunities his daughter could never have in Taliban-controlled Afghanistan.

“My greatest hope will be that my daughter and my son will graduate from university,” he said.

Afghans who worked with the American government for a minimum of one year qualify for a special immigrant visa, but the speed with which the Taliban invaded and the urgency in getting Afghan allies out forced the U.S. to admit the majority of the refugees under humanitarian parole.

Humanitarian parole grants temporary residency and a work permit that expires in one or two years. Unlike special immigrant visas, which provide a path to permanent residency and eventually citizenship, humanitarian parole does not. Because of the temporary status, humanitarian parole beneficiaries are required to apply for asylum within a year of arriving in the U.S.

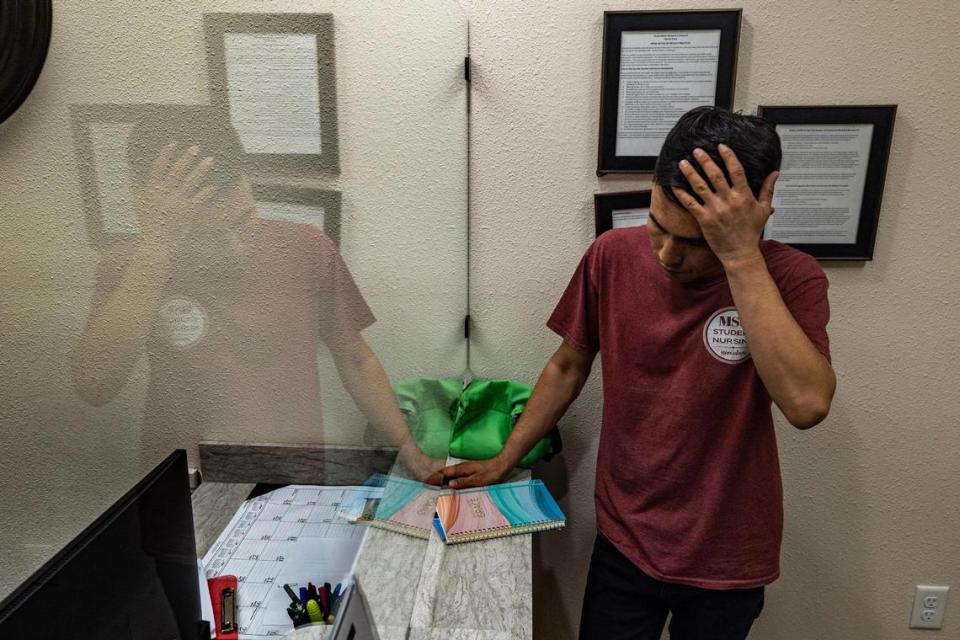

Khan applied for asylum shortly after he arrived in the area, but it was months before he got word that his asylum was approved. In the meantime, his humanitarian parole was set to expire before the end of the year. He was concerned his work permit would expire and he would lose his job at a communications company.

U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services is legally required to prioritize Afghan asylum claims. As mandated by Congress, USCIS is required to conduct the asylum interview within 45 days and give a final ruling within 150 days.

Jacob Oakes, an immigration attorney with the North Carolina-based Pisgah Legal Services and director of the Justice for All program, told the Star-Telegram in August that his organization has Afghan clients who’ve been waiting more than a year for a ruling on their asylum claim.

“(There’s) no end in sight,” he said. “We hope it comes through soon.”

In April, seven Afghans with pending asylum cases sued USCIS for its failure to rule on their cases in a timely manner. On Sept. 11, the plaintiffs reached a settlement with the U.S. government that requires the USCIS to address the backlog in cases and post public status reports of their progress on the USCIS website.

According to Oakes, USCIS is chronically understaffed and underfunded, especially the area that handles asylum claims. Asylum officers have to undergo special training on the process and how to interact in a sensitive way with the applicants, many of whom have experienced traumatic situations in their country of origin. Because of that, the government can’t easily shift employees from another area to help with the asylum backlog, according to Oakes.

D-Ray said he’s grateful for steps the U.S. government has taken, like allowing qualifying Afghans to renew their humanitarian parole, but he’s concerned about the overall slowness of the process.

“These people didn’t arbitrarily show up,” he said. “We brought them here.”

Providing welcome

Refugee resettlement agencies are often newcomers’ first point of contact in the U.S. Briana Vice, regional director of church and community engagement for World Relief, said the humanitarian organization has settled around 540 refugees in the Dallas-Fort Worth area during the 2023 fiscal year, which ended Sept. 30. Vice estimates that 40% of those were from Afghanistan.

Afghans are still fleeing their country, Vice said, and some of them who took refuge in other countries immediately after the Taliban takeover eventually get resettled in the U.S.

World Relief coordinates housing with apartment managers before the refugees arrive. Vice said it’s difficult to find housing for new arrivals because they have no rental history, and some places aren’t willing to take the risk.

As part of their initial resettlement services, World Relief meets new arrivals at the airport, gets them enrolled in English classes and helps them apply for any state benefits they’re eligible for. They also help the arriving refugees find employment so they can become self-sufficient.

These services last for 90 days, but Vice said there are programs, such as cash assistance, that extend beyond that time.

World Relief also provides refugees with a caseworker during the first 90 days, but Vice said caseworkers are responsible for multiple individuals. The organization relies heavily on volunteers in the community who can come alongside and build long-term relationships with refugees as they integrate into life in a new culture. Those interested in volunteering, Vice said, are required to submit an application through World Relief’s website and attend a training. The trainings are virtual in the Dallas-Fort Worth area, and are held the third Tuesday of every month from 6 p.m. to 7:30 p.m.

Information on how to donate or volunteer through Kraus’ nonprofit is found on the Amshera website.

“It just takes normal people,” Kraus said. “Just help somebody.”