‘Just a knee bone’: Reinterment brings pain and healing to Sisseton Wahpeton Oyate

They only found a knee bone.

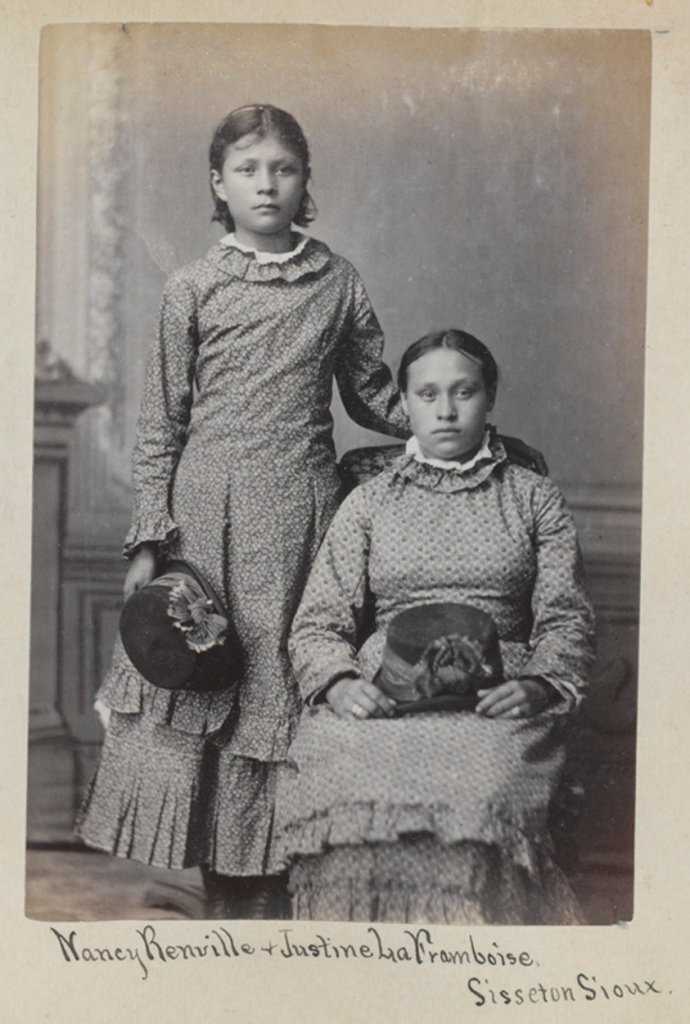

That was all that was left of Amos La Framboise in his grave at the Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Pennsylvania, where the 13-year-old Sisseton Wahpeton boy was sent to assimilate to white culture in 1879. He died just three weeks after arriving at the school.

La Framboise and Edward Upright, also of the Sisseton Wahpeton Oyate, were disinterred by tribal representatives and the U.S. Army this week to be reburied on tribal land, rather than remaining over 1,000 miles away from their homeland. Upright’s grave contained teeth, his skull and other large bones.

The boys’ remains returned to the Lake Traverse Reservation in northeastern South Dakota on Wednesday, to be placed on scaffolds at sunrise and then placed in a tipi each sundown Thursday and Friday before being reburied at noon on Saturday.

The state of La Framboise’s remains infuriates Tamara St. John, Sisseton Wahpeton tribal historian and a member of the South Dakota House of Representatives.

This was the third time La Framboise’s remains have been disinterred. La Framboise’s grave was moved a month after his initial burial from the town’s “White persons’ cemetery” to the school’s newly established private cemetery. Both of the boys’ bodies were disinterred in 1927 after the Army took over the property. The more than 180 children buried at the school were moved to clear space for a new building on the property.

“How careful and loving were you with our child when you dug him up from the Ashland Cemetery and then dug him up again from another?” St. John said.

The singular bone, which matched La Framboise’s gender and age upon death, is a reflection of how poorly Native American children and people were treated and viewed by the United States, she added.

The day before the reinterment process began for La Framboise and Upright, the Puyallup Nation from Washington exhumed what were thought to be the remains of Edward Spott, a 16-year-old boy who died at the school in 1894. Instead, the remains found in the grave belonged to what archeologists estimated were a female between 16 and 22 years old, according to Tiauna Augkhopinee, one of Spott’s relatives who traveled to Pennsylvania to bring his remains home.

“We took care of her as we would take care of our own children and sent her back into her current resting place with love and dignity,” Augkhopinee posted on social media. “Please continue to pray not only for Eddie but for that young lady who is still trying to find her way back to her family. We’ll continue to do this work selflessly, with care and humility.”

Spott is now considered missing, and the remains of the girl will join the more than a dozen other “unknown” graves in the cemetery.

While St. John said she loves the United States, she isn’t surprised that there was “just a knee bone” in La Framboise’s grave.

“I cannot tell you how many times I’ve cried, even though I know I should be happy. People are messaging me that I did it — because I’m the loudest and have been the pushiest,” St. John said, who’s been actively working on bringing the boys home for the past six years.

The Sisseton Wahpeton Oyate struggled with the U.S. Army for years to follow what St. John referred to as a “rigid” reinterment process, having to find next of kin to the boys (who did not have direct descendants) and endure other struggles. The Army took over the property in 1927 after the school closed in 1918, so while the Army was not involved with running the school, the grounds are under the Army’s oversight now.

“At the moment it’s not possible to look at that knee bone and feel much happiness,” she said.

Nevertheless, the process has been a step toward healing. Tribal representatives embraced Army officials they’d fought with for years, and allowed them to observe traditionally private ceremonies.

The Army officials in Pennsylvania helped set up a sweat lodge, sat through prayers, accepted gifts, and took part in pipe smoking and smudging, which is the ceremonial burning of sacred herbs, such as sage, to purify a space or person.

“In the end, I’d like to believe that maybe, just maybe, they have all learned something that might effect change,” St. John said.

She hopes Sisseton Wahpeton’s experience will help other tribes who attempt repatriation. And she was happy that tribal representatives were able to lead ceremonies and prayers and wear traditional regalia while on the school grounds.

“All of those things were intended to be erased at this very place,” St. John said. “But not only are we still here, we’re here with songs and praise.”

St. John said her work has just begun. She is thinking about lobbying for federal legislation to make repatriation efforts easier, or to increase resources for tribal repatriation efforts.

Thousands of Native American children died at the more than 500 boarding schools across the United States and Canada, according to the Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative. Sisseton Wahpeton children went to multiple schools, including the Genoa Indian School in Nebraska where one boy from the tribe, Alfred Brandt, died.

Nebraska officials are trying to find the burial site of the children who died at Genoa. The school operated from 1884 through 1934 with children attending from more than 40 tribal nations.

“This is not something I ever wanted to be an expert in, but that’s what’s happening,” St. John said. “I hope that we don’t become so callous to this that these children’s stories don’t matter. We’re bringing home Amos and Edward, and next it’s going to be Alfred Brandt.”

This article originally appeared on Sioux Falls Argus Leader: Reinterment brings pain and healing to Sisseton Wahpeton Oyate