‘I just want to crawl in a hole and disappear.‘ How a Sacramento mom became homeless | Opinion

On Monday morning, in a one-bedroom, roach-infested apartment in Natomas, Kristie Phillips waited for law enforcement to come and evict her.

She had been told that they would arrive the Friday before, but they never came. Over the weekend, she moved her couch, chairs and other large pieces of furniture under a tarp in the backyard of the small complex, where a man was patching up a hole in the fence thieves had used to break into the car lot next door. The items weren’t necessarily safer outside than in, but at least she’d have access to them after the lock was placed on the door, she thought.

This is not the first time Phillips, 50, has been homeless, and it will likely not be the last. She gave birth to her first two children, now 33 and 31, on Skid Row in Los Angeles while addicted to methamphetamines as a teenager, though she’s been clean for several years now. She said her mother and stepfather first gave her the stimulant when she was 15, and that the family struggled to have stable housing for much of her own childhood.

Every time Phillips tries to dig herself out of the situation she’s in, it just gets deeper. A situation that would be, at worst, annoying for you or I, is a calamity for her: A towed car has spiraled into losing her license and a total lack of transportation; and staying on a friend’s couch has led to tolerating a disgusting apartment. Now, when she tried to force the owners to do better, she’s facing eviction.

It doesn’t matter that she’s been calling every homeless program in Sacramento and beyond, trying to find emergency shelter for herself and her son, because she cannot find assistance beyond being placed on a waiting list. There is no winning when you’re at the bottom of a hole like this, there’s only maintaining surviving until the next calamity comes.

Too often, we only think of “the homeless” as those living in tents on streets corners or under overpasses, but it’s people like Phillips and her children — who always seem to be teetering on the fence line of indigency — that are discounted in our tallies and surveys.

This is what generational poverty and homelessness looks like.

Waiting for eviction

The police didn’t come on Monday either, though she was expecting them to at any minute, all day. That kind of anxiety can take a toll, Phillips said.

“I just want to crawl in a hole and disappear,” she said. “I’m ready to lose my mind. I’m so stressed and I’m so mad. It’s so cold outside right now, and I just don’t know where my son and I are going to go.”

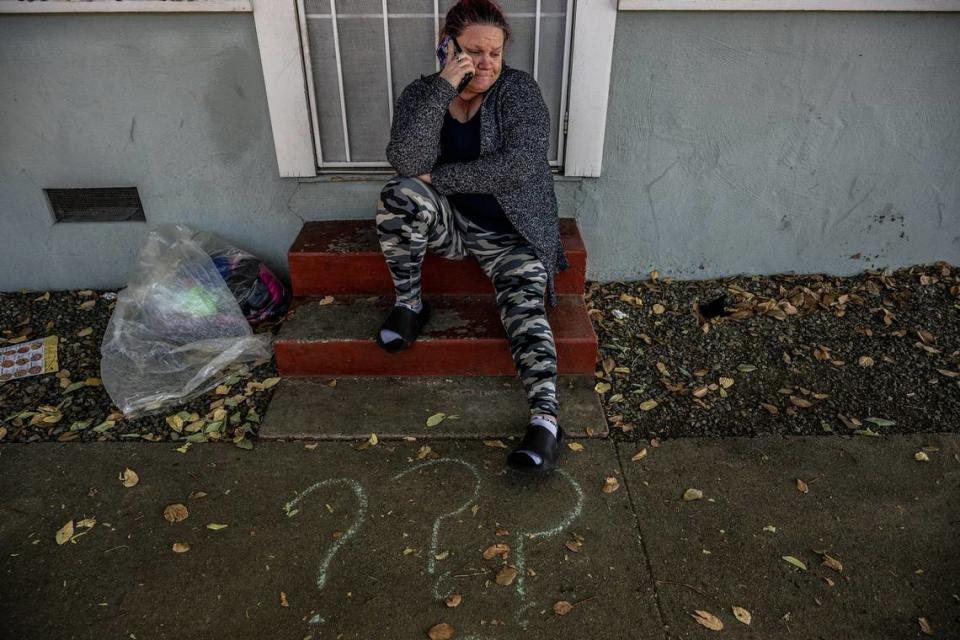

When I met her that morning, Phillips was fielding calls on her cell phone from the few homeless outreach programs who were returning the emergency inquiries she’d made on Friday. At the same time, she was receiving calls from her son’s high school principal; Ty, her 14-year-old son, was truant from class yet again. The principal wanted her to come in for a meeting that day, whenever Ty was found, and discuss his possible expulsion.

But Phillips couldn’t leave her apartment near the corner of West El Camino Avenue and Northgate Boulevard in northern Sacramento even if she wanted to. Her car had been towed several months ago, and she doesn’t have a driver’s license anymore. She also wanted to be there when the police arrived, because she planned to ask them how she could retrieve her family’s possessions which would be locked inside — despite multiple tries, she hadn’t been able to get the apartment manager on the phone to find out what her options were.

When the police didn’t show up that day, Phillips knew she’d have at least one more day with a roof overhead. But she had no idea when that might happen again. She had no plan. She had no help. Her family has been homeless or housing insecure for much of her young children’s lives, and the pressures of poverty have taken a heavy emotional toll on her family.

Generational poverty

While Phillips’ eldest, a daughter, is doing well and lives in the Sacramento region with her own children, her eldest son, Brandon, has also had issues with addiction, which he blames on his mother, she said. He no longer speaks to Phillips.

Her two youngest children, both daughters, have been living with their father up the road, though often stay with their mother when possible. But now, the youngest daughter, 9, has been starting to have behavioral issues at home and at school, Phillips said.

Children who experience housing insecurity are at a much greater risk than the general populace to experience homelessness as adults, said Ryan Finnigan, an Associate Research Director for the Terner Center for Housing Innovation at UC Berkeley.

“When kids are dealing with this instability, obviously it’s more difficult for them to stay more focused in school,” Finnigan said. “That can continue to snowball into lower grades, getting held back or kicked out of school, then they struggle to find jobs that pay living wages. Then all of this can snowball into continued risks throughout their life.”

A U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development report released in 2020 said more than 1,100 homeless people in families with children live in Sacramento, and according to the National Conference of State legislatures, homeless youth generally have much higher rates of early death, and suicide is the leading cause of death for unaccompanied homeless youth.

Phillips said the children’s schools have been far more helpful with finding immediate assistance for the family than any of the city or county’s homeless programs. They’ve been on the city’s Section 8 housing voucher waitlist for more than 14 years.

“I got more help from the school district than I did from (the city),” Phillips said.

When she called the city’s 2-1-1 number, she was told a shelter referral is all they can do. But from prior experience, she said she doesn’t trust the Volunteers of America, because she said they take her food stamps away. And she can’t go to Sacramento’s main women’s shelter — St. John’s Program For Real Change — because her son is too old to stay there.

No one can help

The police finally showed up on Tuesday, “three deep to lock me out,” Phillips said. She has 15 days to come back and get her things before the apartment dispenses with them. Her cat, Macy, was picked up by a foster mom while she and her son cried.

If you’re not facing the imminent threat of sleeping on the street, then it might be easy to dismiss how hard it is to find emergency help. But when the final domino falls and the last bit of shelter is finally torn away from a family, where do they go? There’s no one in Sacramento to call when someone like Phillips and her children are teetering on the edge of homelessness. There’s no magic number to find them shelter for the night.

Phillips has spoken to Sacramento’s Department of Human Assistance, and she’s already called Next Move. They told her to go down to Francis House Center in Midtown Sacramento, but she can’t get any transportation there. She’s also waiting on calls back from Women’s Empowerment and the Black Child Legacy Campaign, both of which contacted her earlier in the week, but nothing and no one has come through yet.

This is not to heap blame on any of these programs. The homeless crisis in Sacramento overwhelms the people trying to help in all sectors of our community

There is no simple solution to homelessness, just as there is no simple number to call to stop a mother of five from sleeping on the street tonight. But that knowledge will be cold comfort for Phillips as the winter sun sets on another day of homelessness.