Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg dies at 87

Ruth Bader Ginsburg, an accomplished advocate against gender discrimination who became one of the most revered justices in U.S. Supreme Court history, has died of complications related to pancreatic cancer. She was 87.

Only the second woman to serve on the Supreme Court, Ginsburg wrote some of the Supreme Court’s most notable opinions on gender discrimination, including the majority opinion in United States v. Virginia, a 1996 case which opened the Virginia Military Institute to women.

Ginsburg’s death seems certain to touch off a political firestorm the likes of which Washington has not seen in decades by offering President Donald Trump the chance to fill a third vacancy on the court and cement its conservative majority.

The Trump administration and its conservative allies lost a smattering of high-profile cases in the past few years by votes of 5-4 with Chief Justice John Roberts joining the court’s liberal justices, prompting grousing from conservative legal activists that — even with two Trump appointees — the court’s rulings were not reliably conservative.

The opening of a vacancy with about six weeks to go before the presidential election will lead lawmakers to revisit arguments about the wisdom and legitimacy of seeking to confirm a new justice to the court when the presidency could shortly change hands.

When Justice Antonin Scalia died in February 2016, Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell quickly announced that he would refuse to entertain any nominee for the seat from President Barack Obama so that voters could weigh in via the fall election.

However, McConnell added a caveat of sorts to his stance, saying that it applied only when the president and the Senate were controlled by different political parties. That proviso was little noticed at the time, but he’s expected to rely on it to move forward with a Trump nominee despite the looming election, even as Democrats accuse him of a transparent double standard.

Ginsburg foresaw the political battle her death would produce. She reportedly weighed in strongly on behalf of holding her seat open and a Democratic victory in November.

"My most fervent wish is that I will not be replaced until a new president is installed,” Ginsburg said before her death, according to a statement released by one of her granddaughters, Clara Spera.

Whoever replaces Ginsburg will be filling the shoes of a trailblazer who began her career at a time when women were a rarity in the practice of law and rarer still at the nation’s top law firms.

“I became a lawyer when women were not wanted by the legal profession,” she said in a 2018 documentary about her life. “I did see myself as kind of a kindergarten teacher in those days because the judges didn’t think sex discrimination existed.”

When he nominated her, President Bill Clinton called her “the Thurgood Marshall of gender equality law.” In 2015, writing about her as one of Time’s 100 most influential people in the world, Scalia compared her to the same former justice: “She became the leading (and very successful) litigator on behalf of women’s rights — the Thurgood Marshall of that cause, so to speak.”

Her influence went far beyond gender cases. In 2012, for instance, Ginsburg authored a vital concurrence/dissent in the split decision for National Federation of Independent Business v. Sebelius, a case that upheld aspects of the Affordable Care Act.

And as the frequency and barbed tone of her dissents increased later in her career, she became a liberal icon, sometimes dubbed “The Notorious RBG.”

“No other justice, however scrutinized or respected, has so captured the public imagination,” wrote Irin Carmon and Shana Knizhnik in a 2015 book of that name. They added: “Across America, people who weren’t even born when Ginsburg made her name are tattooing themselves with her face, setting her famously searing dissents to music, and making viral videos in tribute.”

During the 2016 campaign, she repeatedly blasted presidential candidate Donald Trump and found herself scolded by those who thought justices shouldn’t get involved in partisan politics — and the target of a Trump tirade. “Justice Ginsburg of the U.S. Supreme Court has embarrassed all by making very dumb political statements about me.” Trump tweeted in July 2016.

Ruth Bader Ginsburg was born Joan Ruth Bader on March 15, 1933, in Brooklyn, daughter of Nathan and Celia Amster Bader. Her kindergarten class was loaded with Joans, so she became just Ruth.

It was her mother who encouraged her to read by taking her to a public library in Brooklyn above a Chinese restaurant. “Ever since, Ruth has associated the aroma of Chinese food with the pleasure of reading,” wrote Elinor & Robert Slater in “Great Jewish Women.”

Growing up during the Holocaust, she came to identify with her fellow Jews who were persecuted by Nazi Germany. Decades later, in the anthology “I am Jewish: Personal Reflections Inspired by the Last Words of Daniel Pearl,” she would write: “I am a judge, born, raised, and proud of being a Jew. The demand for justice runs through the entirety of Jewish history and Jewish tradition.”

Her mother died of cancer two days before she graduated from James Madison High School.

“Watching the physical deterioration of the parent who represented nurture and security, along with her father’s silent grief, had been anguishing for the sensitive adolescent,“ wrote biographer Jane Sherron de Hart. “Yet with Celia’s encouragement, she won prestigious college scholarships, played in the school orchestra, and cheered on the football team as a baton twirler — never once revealing to her schoolmates the illness that shadowed the Bader household in Flatbush.“

Despite her horrible loss, Ruth went on to attend Cornell University, where she excelled — and also met and married Martin Ginsburg.

From Cornell they went to Fort Sill in Oklahoma, where he served in the Army and she gave birth to a girl, Jane. The family moved on together to Harvard Law School, where she would become one of nine women in her class — and would find herself facing discrimination for her gender.

“Ginsburg attended a dinner in honor of women students that was a major turning point for her,” wrote the Slaters in 1998. “She was aghast at the words of the dean, who was host, as he asked each woman to explain what she was doing at the law school occupying a seat that could have been filled by a man.”

Ginsburg ended up literally occupying a seat that was supposed to be occupied by a man: Her husband was diagnosed with testicular cancer, and she attended his law classes as well as hers as he recuperated. (Martin recovered and had his own notable legal career. He died in 2010 at the age of 78.)

When her husband accepted a job in New York City, she transferred to Columbia Law School to finish her education. Although she was a top-flight student, New York firms were not interested in her. “The traditional law firms were just beginning to turn around on hiring Jews. But to be a woman, a Jew, and a mother to boot — that combination was a bit too much,” Ginsburg later wrote. Supreme Court Justice Felix Frankfurter also declined to hire her, saying he was not ready to employ a female law clerk.

She eventually joined the faculty of Rutgers (N.J.) Law School and came to be a prominent advocate for gender equality, then became the first woman to become a full professor at Columbia. Ginsburg also gave birth to a second child, a son named James, in 1965.

In the 1970s, she participated in a series of gender discrimination cases before the U.S. Supreme Court in connection with the American Civil Liberties Union and its newly created Women’s Rights Project.

At issue was that the nation’s top court had never treated laws or government policies that discriminated against women as necessarily violating a fundamental right. It didn’t help that some of the laws in question were written by male lawmakers to make it seem as if they were benefiting women, by keeping them from having to deal with difficult situations that were — in the thinking of those male lawmakers — best left to men.

“Race discrimination,” Ginsburg said at her confirmation hearing in 1993, “was immediately perceived as evil, odious and intolerable. But the response that I got from the judges before whom I argued when I talked about sex discrimination was: ‘What are you talking about? Women are treated ever so much better than men.’”

Reed v. Reed (1971), for instance, dealt with an Idaho law that gave preference to a dad over a mom in administering their late son’s estate. In 1972, she successfully advocated for Susan Struck (Struck v. Secretary of Defense), who had been told she needed to terminate her pregnancy if she wanted to stay in the Air Force, clearly an issue a man would never face.

Within the all-male Supreme Court, Ginsburg found an advocate for her viewpoint in Justice William Brennan, who had been the cornerstone of the liberal Warren Court and who was still able to sometimes build a majority on the more-conservative Burger Court. Of the six gender-discrimination cases Ginsburg argued in the 1970s, she won five.

“To challenge those laws,” according to “Justice Brennan: Liberal Champion“ by Seth Stern and Stephen Vermeil, “she purposely sought out cases ‘with a strong human appeal,‘ aware that justices would not naturally relate to a woman’s experience.”

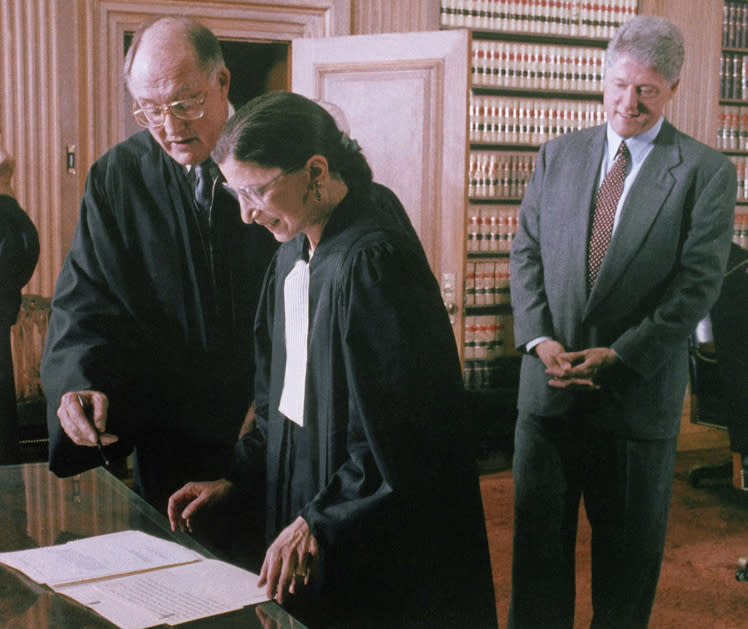

In 1980, President Jimmy Carter picked her for the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit. Thirteen years later, with the retirement of Justice Byron White, Clinton had the opportunity to appoint a Supreme Court justice for the first time and selected Ginsburg.

“Throughout her life,” Clinton said in announcing Ginsburg’s nomination, “she has repeatedly stood for the individual, the person less well-off, the outsider in society, and has given those people greater hope by telling them they have a place in our legal system.”

She was confirmed by a vote of 96-3. “By any measure,” said then-Senate Minority Leader Bob Dole (R-Kan.), “she is qualified to become the Supreme Court’s ninth justice.”

“Ginsburg is known as a ruthless editor with a keen eye for detail," wrote Edith Lampson Roberts soon afterward in “The Supreme Court Justices: Illustrated Biographies, 1789-1995." “Her soft voice and reserved manner hide great perceptiveness and a warm interest in people.”

Though tagged as a liberal, Ginsburg was an advocate for judicial restraint, arguing against attempting to legislate through judicial fiat. At times, she was critical of the 1973 Roe v. Wade decision not because she disapproved of legal abortion but because she thought the court had overreached.

“Ginsburg is professional, polite and extraordinarily precise in her opinions and questions,” wrote Laurence Tribe and Joshua Matz in their book “Uncertain Justice: The Roberts Court and the Constitution.” “She cares deeply about the role of the Court and frequently speaks about the need to find a balance between advancing constitutional values and respecting the Democratic process.”

She wrote a landmark opinion in the 1996 VMI case, which allowed women to enroll at the military academy, the nation’s last all-male public university. “It may be,” Ginsburg wrote for the court, “that many women would not want to go to VMI, but many men would not, either. And as long as there are qualified women who want to go — and there are — they must be admitted.”

National Federation of Independent Business v. Sebelius, the 2012 case in which a divided court upheld most but not all of the Affordable Care Act, saw another of her most consequential opinions — part concurrence, part dissent. “Congress had a rational basis for concluding that the uninsured, as a class, substantially affect interstate commerce,” she wrote.

In 2000, she was one of four dissenting justices in the emergency case of Bush v. Gore, which decided the presidential election. “The Court’s conclusion that a constitutionally adequate recount is impractical is a prophecy the Court’s own judgment will not allow to be tested. Such an untested prophecy should not decide the Presidency of the United States,” she wrote. “I dissent.”

Another notable dissent came in Gonzales v. Carhart, a 2007 case in which the court upheld the Partial-Birth Abortion Act of 2003. “Legal challenges to undue restrictions on abortion procedures do not seek to vindicate some generalized notion of privacy; rather, they center on a woman’s autonomy to determine her life’s course, and thus to enjoy equal citizenship stature,” she wrote. In 2013‘s Shelby County v. Holder, she blasted the majority’s decision to gut elements of the Voting Rights Act: “The Court’s opinion can hardly be described as an exemplar of restrained and moderate decision-making. Quite the opposite. Hubris is a fit word for today’s demolition of the VRA.“

Over the years, she developed a close friendship with Scalia, a bond they maintained despite significant ideological differences.

“Ruth and I disagree on the law all the time,” Scalia said at a joint forum in 2014. “But that has never had anything to do with our friendship.”

Scalia and Ginsburg both loved opera. In 1994, the two joined together to appear as extras in a Washington Opera production of a Richard Strauss opera. She also joined Justices Anthony Kennedy and Stephen Breyer on stage in 2003 in “Die Fledermaus.”

In 2013, she lectured on the subject of “Law in Opera” at the Chautauqua Institution in western New York. That was the same year a musician named Derrick Wang set Scalia-Ginsburg arguments to music in an opera called “Scalia/Ginsburg.”

“They liked to fight things out in good spirit — in fair spirit — not the way we see debates these days,” NPR’s Nina Totenberg observed as the time of Scalia’s death in 2016.

The court’s official statement announcing Ginsburg’s death declared that she “died this evening surrounded by her family at her home in Washington, D.C., due to complications of metastatic pancreas cancer.”

Ginsburg is to be buried at Arlington National Cemetery, the statement said.

“Our Nation has lost a jurist of historic stature. We at the Supreme Court have lost a cherished colleague. Today we mourn, but with confidence that future generations will remember Ruth Bader Ginsburg as we knew her – a tireless and resolute champion of justice,” Roberts wrote.

Ginsburg struggled with bouts of cancer for more than two decades. In 1999, she was diagnosed with colon cancer, but recovered after surgery and radiation therapy. A decade later, an annual exam turned up early-stage pancreatic cancer, prompting another round of surgery.

In 2018, Ginsburg was struck by lung cancer, which a court statement said was discovered by chance while she was being treated for a fall in which she broke two ribs. Surgery followed to remove two nodules but no further treatment was planned, the court said.

While Ginsburg prided herself on not missing any court arguments during her earlier bouts of illness, she missed two weeks of oral arguments in January 2019 as she recovered from the lung cancer surgery.

In August 2019, the court announced that Ginsburg’s pancreatic cancer had recurred and that she underwent a non-surgical, radiation treatment to shrink the tumors. She later claimed to be cancer free.

While Ginsburg drew kudos for her tenacity and became a testament to the success of modern medicine in managing cancer, she was often sluggish to disclose bad news she’d received from her doctors, perhaps out of fears of alarming her legions of supporters.

In February of this year, Ginsburg was notified that a scan had found lesions on her liver, marking her fifth known occurrence of cancer. The diagnosis prompted a biopsy and then immunotherapy. When that was unsuccessful, she began chemotherapy in May.

However, she offered no public indication that her cancer had returned until July, after two intervening hospitalizations for other illnesses that were announced by the court but portrayed as minor.

Although Ginsburg was not always prompt in announcing her health setbacks, court observers noted that other justices are more reserved or entirely silent about their medical conditions. Five of the eight remaining justices are 65 or older and it is common for justices to remain on the bench into their 80s.

Ginsburg was last seen by the public in late August via a photo posted on Twitter of her officiating at a wedding of a couple described as family friends of the justice.

"There is nothing like a cancer bout to make one relish the joys of being alive,” she said in 2001, after her first brush with the disease. “It is as though a special, zestful spice seasons my work and days. Each thing I do comes with a heightened appreciation that I am able to do it."

Though slight in appearance — and despite her long-running battles with cancer — Ginsburg was a physical dynamo, known for her ambitious workouts. “People who think she is hanging on this world by a thread underestimate her,” wrote Carmon and Knizhnik in their 2015 book. “RBG’s main concession to hitting her late seventies was to give up water skiing.”

Ginsburg’s fitness regime became legendary, with videos of her workouts circulating widely. In 2017, a POLITICO reporter described his efforts to match her routine in an article headlined, “I Did Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s Workout. It Nearly Broke Me.”

Her energy carried her well beyond Washington, as she found herself in considerable demand as a speaker.

“Soaking in her late-in-life emergence as a liberal icon,” the Associated Press wrote in January 2018, “she’s using the court’s month-long break to embark on a speaking tour that is taking her from the Sundance Film Festival in Utah to law schools and synagogues on the East Coast.”

Her honors sometimes took forms unusual for a jurist. In 2016, it was announced a new species of praying mantis from Madagascar had been named for her. Scientists from the the Cleveland Museum of Natural History said they had named the species Ilomantis ginsburgae because of “her relentless fight for gender equality.”

Justices had been the subject of occasional cinematic biographies dating at least back to Oliver Wendell Holmes and 1950‘s “The Magnificent Yankee.” But in 2018, Ginsburg was the subject of two: “RBG,” a documentary, and “On the Basis of Sex,” in which she was portrayed by Felicity Jones. At the time of the release of the latter, POLITICO’s Peter Canellos said it was only the tip of the iceberg in terms of Ginsburg adulation, noting fans could also choose “from four biographies, five children’s books, a coloring book, a workout book, an action figure, an ‘historic Ruth Bader Ginsburg notebook,‘ a throw pillow and a robe-bedecked figurine.”

Ginsburg was the court’s oldest sitting justice and the second-longest-serving member of the court’s current bench.

Justice Clarence Thomas, who was nominated by President George H.W. Bush in 1991, is the most senior justice. With Ginsburg’s passing, the oldest current member of the court is 82-year-old Justice Stephen Breyer, a Clinton appointee.

The last president to install more than two justices on the court was President Ronald Reagan, who filled three vacancies, as Obama could have had Merrick Garland been confirmed.