Juvenile justice reforms are passing after task force's 'monumental' two-year effort

A fleet of bills working their way through Michigan’s Legislature are aimed at reforming how the state approaches and administers juvenile justice. Members of the Task Force on Juvenile Justice Reform said the legislation will create a more equitable system that accounts for children’s mental health, expands options for diversion, and considers kids’ underlying needs.

“I really view these reforms as transformative,” said Jason Smith, executive director of the Michigan Center for Youth Justice. “It shifts the juvenile justice system here in Michigan into one that's more evidence-based, data-driven (and) really focuses on expanding community-based care options for treatment and services for young people who come in contact with the justice system …”

Though task force members agreed more work must be done both in the Legislature and within the judiciary and state agencies, they agreed that the bills now working their way to the governor’s desk represent massive changes to the juvenile justice system’s treatment of children as a special population in need of support, not just punishment.

An expedited effort to reform the juvenile justice system

Gov. Gretchen Whitmer created the Task Force on Juvenile Justice Reform in June 2021 as a temporary advisory body within the Department of Health and Human Services, charged with analyzing Michigan's juvenile justice system and recommending changes to state laws, policies and appropriations aimed at improving youths' outcomes.

Just over a year later, the task force released a report showing that Michigan lacked uniform policies and quality assurance standards. These variances led to disparities for youths, a lack of quality care for some and unreliable data for the state.

The bipartisan package of 20 reform bills, making their way through the Legislature one year after the task force released its report and recommendations aims to smooth that patchwork approach to juvenile justice.

“From funding to diversion to community-based programming enhancements, it’s monumental to get that amount of work done and to have it done so collaboratively,” said Thom Lattig, president of the Michigan Association for Family Court Administration and juvenile court director of the 20th Circuit Court. “I think that that's the biggest thing, is just being able to make sure there's more consistency and uniformity across Michigan and the way juvenile justice is dispensed.”

Michigan in 2021 saw 20,762 dispositions in juvenile circuit court and more than 2,000 consent calendar proceedings, the latest year for which there is data.

More money means more options

One of the primary changes this legislation would create is the way programming and care are paid for.

SB 418, which passed in the Senate and is now on its second reading in House, would require the DHHS Child Care fund to reimburse counties at a rate of 75% of annual expenditures for in-home expenses for juvenile justice, up from the current rate of 50%.

The Child Care Fund reimburses counties and tribes for placement costs and community-based programming such as counseling, family reunification, probation and drug court for children in the juvenile justice system.

Proponents of SB 418 and a comparable bill in the House say boosting the reimbursement provided through this fund will strengthen and expand community-based services that can keep kids out of detention.

Smith said it will also allow for state money to be used for diversion pre-arrest — a huge improvement over the current setup, under which a charge must be filed in order for the fund to kick in for diversion programming. That creates delays in getting juveniles the interventions they need to change course, Smith said.

“Creating a vehicle to be able to serve kids much more upstream I think will yield positive results, for the young people but then also the system, because they can focus their more intensive resources on the kids who truly need that that court supervision,” Smith said.

The changes would also allow this particular pot of money to be spent establishing places besides detention centers or emergency rooms for youths to go in a crisis.

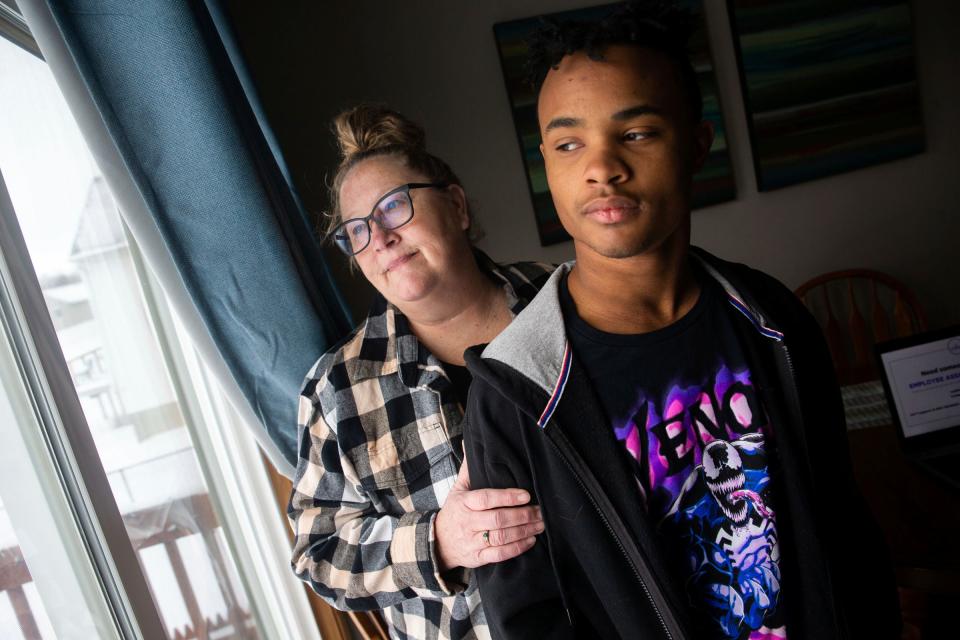

Cole Williams, a family court parenting consultant and a member of the task force on juvenile justice reform, said that might have helped his own son stay out of the justice system.

Williams called the police when his son was acting out during a mental health crisis, thinking it was his only resource. “When you don’t have any other options, you become desperate,” he said.

Williams said the elevated funding for community programs and emergency options would create pathways to services instead of just an on-ramp to detention.

A focus on risks and needs

Several of the bills working their way to the governor’s desk put a new spotlight on children’s mental health and other needs of justice-involved youths.

“What you see here is a focus on identifying mental health risks or concerns with youth in the juvenile justice system and helping to address those early on, to give those youth more wraparound services, because really our goal is for them to never come back through the juvenile justice system,” said Elizabeth Clement, chief justice of the Michigan Supreme Court and a member of the task force. “We can't accomplish that if we're just punishing kids and we're not addressing what their underlying issues are, whether that’s mental health concerns or family concerns (or) educational concerns.”

Senate and House bills that have passed include requiring screening tools to help counties identify a child’s risk and needs and make decisions about diversion, detention and disposition — one of the task force’s unanimous recommendations. These tools must be used to help inform decisions about placing a juvenile’s case on the consent calendar, a less formal process of court supervision that provides a plan for correction and allows young people to avoid entering a plea and facing criminal prosecution.

Recommendations for disposition must consider public safety and victim interests but must also strive to place the juvenile in the least restrictive setting possible and consider rehabilitation and education.

“I hope there are opportunities where we can help divert more youth that are dealing with mental health instead of criminalizing their behaviors,” Lattig said. “I think the legislation goes a long way to doing that with the diversion and consent calendar legislation, asking that more low-risk kids be pushed away from the system into the resources they need.”

HB 4633 would modify the factors a court would need to consider before trying a juvenile as an adult, only allowing previous delinquent behavior to be weighed if it would have also been considered a crime if committed by an adult. It requires considering the child’s developmental maturity, emotional health, and mental health, and the impact on any victim.

If the juvenile is a member of a federally recognized Native American tribe, the court would also have to honor the culture and values of their tribe.

“I don't really feel like in my lived experience … that parents have ever felt like they have had a partnership,” said Williams. “These bills give us an opportunity to reimagine what collaboration and partnership looks like, and it really forces people to actually look at what's really happening to families in Michigan.”

Wiping out court fees for families

While some counties charged families for costs associated with paying attorneys, administering probation and testing for drugs among other things, the approach was court-specific and therefore, advocates said, inequitable.

Several of the bills in the reform package would do away with discretionary court fines and fees entirely.

Families would no longer be billed for the costs of care, services, court-appointment attorneys or other court fees — or for the cost of a juvenile’s out-of-home care if the court decides on such a placement.

Starting in October 2024, legislation would prevent courts from collecting on previously assessed court fines and fees that advocates said were damaging to families and had been applied unevenly across the state, and removes the option for the court to go after anyone’s tax refunds in an effort to recoup court costs or unpaid costs for care.

“This is really focused on shifting the system to focus on treatment over punishment,” said Smith, who said he has spoken with families who are over $100,000 in debt from juvenile court fines and fees, which vary widely by county.

“As a reform that really going to impact families day-to-day, they see and feel it, that the elimination of fines and fees is going to be a huge reform for Michigan,” he said.

More equitable juvenile defense

Currently, the Indigent Defense Commission and the State Appellate Defender’s Office, which assist adults convicted of felonies and provide for indigent defense, cannot offer these same services to juveniles.

New legislation would lay the foundation for Michigan to establish more expansive and uniform training and standards for attorneys representing youths in the system, and ensure all children have access to representation.

“It's going to be transformational for youth and families,” Clement said.

SB 425 creates a system of appellate defense services for indigent youth and requires the appellate defender commission to compile and keep updated a statewide roster of attorneys who are eligible and willing to defend juveniles who can’t otherwise afford to hire a lawyer.

The state won’t fully reimburse the indigent defense system for three years, and funding for it is subject to appropriation, though the bill says, “It is the intent of the Legislature to fully fund this reimbursement.”

HB 4630 specifies that indigent defense systems must serve youths as well as adults, and requires new standards be set for determining who qualifies as indigent. It also expands the Michigan Indigent Defense Commission’s membership to include an attorney with experience defending youths.

The bill would specifically prohibit juveniles from waiving the right to counsel unless the youths were advised on the consequences of doing so and waived his or her rights in writing.

Right now, Michigan has no standards about representing indigent youths, according to University of Michigan law professor Kimberly Thomas, who co-directs its Juvenile Justice Clinic. People who represent teenagers aren’t required to have any knowledge about working with teenagers or understanding of adolescent development.

She said bills now before the House and Senate would provide a framework of minimum standards that would include specialized training and supports for counselors working with juveniles.

“I think that you'll see (that) just being able to communicate and explain to a teenage client and have them understand what's happening to them in the court process is a really big deal,” Thomas said. “And I think that this really moves us in the direction where young people can feel like they can understand what's going on, they can make choices for themselves, they can have their voices heard — and that's really important.”

Expanding child advocacy to juvenile justice

SB 432 establishes the office of the child advocate, which would replace the children’s ombudsman office. While the children’s ombudsman office was concerned with children's suffering abuse and neglect, the office of the child advocate would include justice-involved kids and residential facilities in its purview.

The office will continue to investigate complaints and protect the welfare of kids who are under state or court jurisdiction, control or supervision. The bill adds language to allow the child advocate to investigate the deaths of any children who died while committed to a residential facility.

HB 4639, 4640 and 4643 amend the state’s acts and codes to refer to the Office of the Child Advocate and expand its jurisdiction to juvenile facilities in order to monitor the safety of children there as it does those in the child welfare system.

Cornelius Frederick notably died after being restrained by staff in a group home he’d been placed in.

Under this bill, the governor would appoint a child advocate — and has the power to remove one.

A few other bills make distinct changes, such as SB 426, which would allow DHHS to adjust the juvenile justice residential per diem rate as needed — within the amount appropriated in the annual budget — and make changes to provider service agreements to respond to bed shortages and staffing needs.

Jennifer Brookland covers child welfare for the Detroit Free Press in partnership with Report for America. Reach her at jbrookland@freepress.com.

This article originally appeared on Detroit Free Press: Juvenile justice reforms pass in legislature with mental health focus