Here’s What Kamala Harris Faces as a ‘First’

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

So many firsts. First woman. First Black vice president. First Black woman vice president. First South Asian American. First South Asian American woman. First VP whose parents come from India and Jamaica. First VP who counts Prince and Bootsy and hip-hop among her musical loves. First VP who’s a stepmom. First VP to be a member of Alpha Kappa Alpha. First HBCU grad. First vice president married to a man …

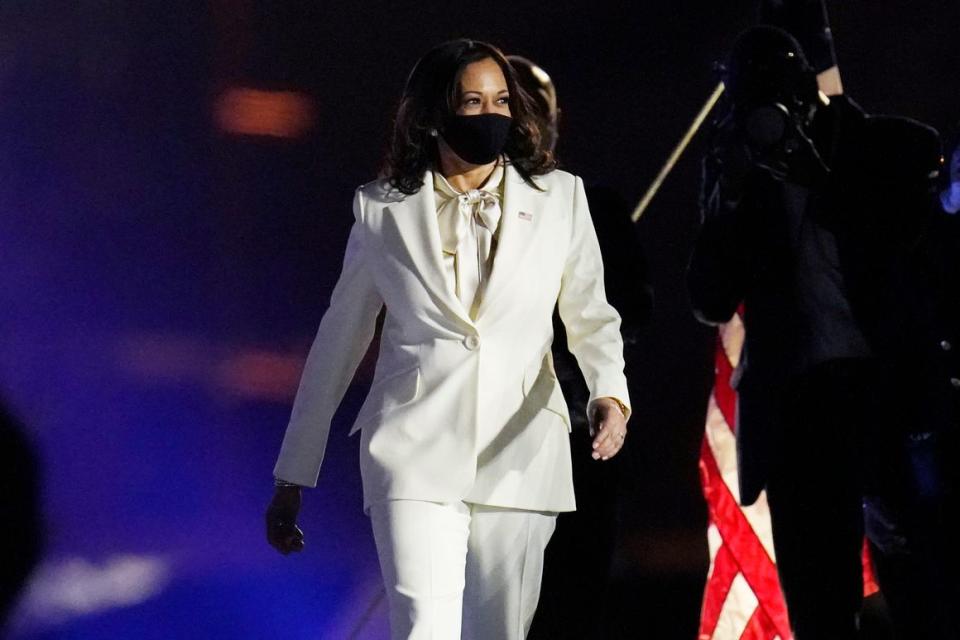

Kamala Harris, who made her acceptance speech Saturday night in suffragette white, may claim more “first evers” than any other politician sworn into national office. And another: She’s the first vice president-elect to do a victory lap to the beat of Mary J. Blige.

Memes abound.

Within moments of the election being called, corners of the internet erupted with what looked a lot like joy, infused with a sense of long-delayed arrival for huge swaths of Americans. There’s the picture of Harris in profile, decked out in a power suit and power pumps, striding forward … and on the wall behind her, the shadow of a little girl in pigtails, also striding forward, a reference to the iconic Norman Rockwell portrait of civil rights hero Ruby Bridges. There’s the video roll call of all the previous vice presidents, a long line of white male faces (and one biracial Native American), finally landing on Harris’ smiling brown face. There’s the tweet from "Veep" star Julia Louis-Dreyfus, “Madam Vice President is no longer a fictional character.”

And then there’s Harris’ niece, Meena, tweeting, “My four year old just yelled, BLACK GIRLS ARE WELCOME TO BE PRESIDENT!”

My 4 year old just yelled “BLACK GIRLS ARE WELCOME TO BE PRESIDENT!”

— Meena Harris (@meenaharris) November 7, 2020

As that vice presidential roll call reminds us, Harris has been inducted into one of the world’s most exclusive clubs, the people who’ve occupied the American vice presidency. Come January 20, Americans will watch her hopping into motorcades, popping out of helicopters, walking surrounded by the Secret Service, breaking ties in a divided U.S. Senate.

But in this moment, she’s also joining an equally exclusive club of first-evers, women of color who aimed their stilettos—or Chucks—at glass ceilings and kicked. In the past few decades, America has seen a cavalcade of firsts: the first Black woman in the Senate, the first Latina Supreme Court justice, the first Black woman Ivy League university president. … And in the House, we’ve also seen a litany of women serving as the first: an American Indian woman elected to Congress, an Indian immigrant, two Muslim women, a Haitian American.

The roads these other “firsts” traveled in American politics offer some lessons for Harris, suggesting that sense of triumph should be tempered with caution. In interviews with other “firsts” and in the analysis of historians, they suggest the path for Harris will be unpredictable, at best. Their accounts, and their biographies, speak to a truth about America familiar to many women of color: When you assume power, there are high expectations. You become, effectively, a one-woman band with a mandate to defy all the low expectations of you, your race and your gender.

“[It’s been said] you can always tell a pioneer by the arrows in your back,” said former Sen. Carol Moseley Braun (D-Ill.). “There were a lot of arrows I hadn’t anticipated. At the same time, it was really a life-changing thing for me.”

As the first Black woman to serve in the Senate, Moseley Braun found herself facing scrutiny for everything from her relationship with her then-fiance to her stance on welfare reform to alleged ethics violations to the way she looked in a Chanel twin set.

Everything she did, she said, was seen through the prism of her race and gender. “You really are held to a higher standard, a different standard,” said Moseley Braun, who, after losing her reelection bid in 1998, went on to serve as U.S. Ambassador to New Zealand. “It was not an easy row to hoe. I had to pray a lot, obviously, just to keep from losing my mind.”

After one particularly tough day on the floor, Moseley Braun recalls sitting at home, having a “pity party.” Until she turned on the TV. “Roots” was playing. She switched the channel. There was “The Autobiography of Miss Jane Pittman,” starring Cicely Tyson as a formerly enslaved centenarian. She changed the channel again, only to see “Rosewood,” a biopic about the massacre of a middle-class Black Florida town at the hands of a white mob.

“I stood in the middle of my bedroom, looked up at the ceiling and said, ‘You’re just messing with me,’” Moseley Braun said, laughing. “I had no reason to have a pity party—there were people who literally died to make sure I could go to the Senate.”

Harris, the daughter of immigrants, has also faced the dual hits of racism and misogyny. She’s dealt with accusations she’s not Black enough, or too Black—or not Black at all. She’s dealt with sexist memes about her relationship with former San Francisco Mayor Willie Brown, criticisms that she’s too strident (“monstrous”) or that she's “embarrassing” and “frivolous” because she likes to dance in the rain.

Those are tropes about women of color, particularly Black women, that are as old as the republic itself, where racial differences have been used throughout history to justify slavery and ongoing inequality, says historian Paula Giddings, author of When and Where I Enter: The Impact of Black Women on Race and Sex in America. Black women in the public eye are cast as either the hypersexual Jezebel, if they fit conventional beauty standards, or the asexual mammy/matriarch if they don’t. Investigative journalist and activist Ida B. Wells, another first, was often cast as the Jezebel, called a “slanderous and nasty minded mulatress” by the New York Times in 1894.

And when these women, these firsts, make a push for power, they sometimes encounter resistance from their male compatriots. When Congresswoman Shirley Chisholm (D-N.Y.) became the first Black American to run for president in 1972, African American women overwhelmingly supported her, while Black men did not, said Beverly Guy-Sheftall, feminist scholar and director of the Women’s Research and Resource Center at Spelman College. In Harris’ case, an October survey found only one-third of Black men thought it was a good idea for President-elect Joe Biden to tap a Black woman for vice president.

“Men [of all races] often push back when a woman is in a space that they think should be theirs,” said Giddings, professor emerita of Africana studies at Smith College. “It can be very unsettling. These figures symbolize disturbing the peace.”

Beauty, too, can both help and hinder. Barack Obama caught flak for describing Harris, then the California attorney general, as “the best looking attorney general in the country.” And part of Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez’s appeal, besides her intellect and fire, is her striking looks. And at the same time, her looks seem to anger some men, Giddings said.

Author and TV producer Padma Lakshmi, who sees Harris’ election as “a very big moment,” personally can relate. She was the first Indian top model in the ’90s, and later, breaking into television with “America’s Top Chef,” encountered naysayers. It’s as if you can’t be good looking “and be an eloquent speaker and be a hard worker and be all these things,” Lakshmi said. “It creates ire in people sitting across the aisle.”

These are burdens that all women in office must hoist, said Rep. Pramila Jayapal (D-Wash.), the first South Asian woman to serve in Congress. Either you’re too pretty, or you’re not pretty enough, and they “tie their dislike of you to your appearance.” Add race and ethnicity and immigration to the mix, and the burden can feel even heavier.

“There is this constant sense of. ‘I gotta do more. I gotta do better,’” Jayapal said. “Everyone puts their hopes and dreams on you.”

Amid the hopes and dreams will come some tough political battles ahead. Harris and President-elect Joe Biden will have to govern a weary and divided nation, still fighting a pandemic, with a partly hostile Congress—and an ex-president expected to undermine their efforts. But Harris is an integration baby who grew up having to navigate all kinds of different cultural terrains. And as the women before Harris learned, being the first, and constantly having to combat stereotypes, builds the kind of grit that can serve as good preparation for the fights she’s likely to face after Inauguration.

Ultimately, being the first—being chosen as a first—is a privilege, and Jayapal said the South Asian community was over the moon by Harris’ ascent. “We are so proud. We are just so proud of her,” Jayapal said. “And we’re proud of her, not only for being the first South Asian person elected … but also being the first Black woman. That is also significant to us. We’re proud of her for all of her identities.”

Saturday night, Harris seemed to tap into all of that, the pride, the hope, the expectations and the path cleared by other women. “Black women, Asian, white, Latina, Native American women—who … have paved the way for this moment tonight. Women who have fought and sacrificed so much for equality and liberty and justice for all.”

“There is joy in it and there is progress,’’ Harris said. “Because we the people have the power to build a better future. … You ushered in a new day for America.”

CORRECTION: This story has been updated to correct quotes from Harris’s speech.