Kamala Harris knows how to 'throw an elbow': How California politics shaped the 2020 hopeful

SAN FRANCISCO – Sen. Kamala Harris shocked fellow presidential hopeful Joe Biden at the Democratic debate in Miami last month by dressing him down over busing. She immediately saw her poll numbers jump and the nation got a glimpse of a steely competitor.

But for those who have been a part of Harris’ long tenure in California politics, the moment was pure déjà vu – a vintage Harris move fostered in the bare-knuckled, hyper-competitive cauldron of Bay Area politics.

“San Francisco is a political crucible that has chewed up and destroyed a lot of fairly talented and ambitious people,” says Dan Newman, a close adviser to California Gov. Gavin Newsom who also was a strategist on various Harris campaigns.

“There’s an intense interest in politics here, robust political journalism and an engaged electorate,” he says. “Those who have the ability to survive and thrive here tend to do so at broader national level.”

Harris, who gets both another chance to show the nation her stuff and a Round Two with Biden during the next Democratic debates on July 31, showed early on that she had such mettle.

In 2003, during her first run for public office as San Francisco’s district attorney, Harris faced down two male rivals, incumbent Terence Hallinan and former prosecutor Bill Fazio.

Harris’ political consultant, Jim Stearns, warned her that the men would choose an upcoming public meeting at a city church to attack her candidacy as being propped up by kingmaker and then-Mayor Willie Brown, whom Harris briefly had dated in the mid-90s.

“Those two men quickly learned what Joe Biden found out in Florida,” Stearns says. “You don’t mess with Kamala Harris. There’s always a double bind for female candidates, but she’ll throw an elbow if she needs to.”

In Stearns’ retelling of the event, Harris calmly walked around her rivals and – after casually mentioning that Hallinan had pilloried Fazio for being caught at a massage parlor, and Fazio had criticized Hallinan for staffers having sex at work – told the crowd the race should be run on the issues only.

“The whole crowd stood up and applauded,” Stearns says with a laugh. “We never heard about Willie Brown after that.”

Harris has her detractors

Harris' impressive resume mushroomed from there. The one-time city attorney, now 54, became the first female – let alone biracial race – district attorney in the city’s history, winning again four years later before claiming another brass ring as California's first female attorney general in 2010.

She was reelected by a wide margin in 2014, and then successfully ran for a U.S. Senate seat vacated by veteran Democrat Barbara Boxer in 2016. Harris' Senate move allowed then-Lt. Gov. Gavin Newsom to successfully push for the governor's perch last fall, a plum that might have gone to his friendly rival and peer had she sought that office.

Now, Harris has her eyes on a new prize, the presidency.

Despite her scene-stealing moment at the debates and her campaign's subsequent gains, Harris lags in polling and fundraising against the Democratic front-runner, former Vice President Biden.

Harris also is second to Biden in recent California polls, increasingly a critical gauge of success ever since the massive blue state announced it was moving up its primaries to March 2020, making a victory in the Golden State imperative for any Democratic nominee looking to stand out after first-in-the-nation contests in Iowa and New Hampshire.

Harris, of course, has her detractors, most of whom point to her law enforcement days in San Francisco and Sacramento as evidence of establishment bona fides that are at odds with the growing progressive choir in the party as exemplified by freshman Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, D-N.Y.

"Harris's work as DA and California AG cannot be described as progressive," says Gayle McLaughlin, chair of the California Progressive Alliance, a volunteer-based network that promotes progressive ideals.

"She has a reputation for protecting the status quo and shrinking from controversial issues," says McLaughlin, citing Harris's tough-on-crime approach that saw some parents arrested for their children's truancy. "California progressive activists are well aware of her opposition to or silence on many criminal justice reform issues."

Some Bay Area political experts also question whether Harris, who drew 20,000 supporters for her campaign kick-off rally in her native Oakland, can draw the support of African American voters, long considered a key constituency for Democratic candidates. The issue, again, is her law enforcement background.

"She calls her approach being smart on crime, but it seems she just found a less racist way of using the police apparatus to carry out her duties," says James Taylor, who lectures on politics and African American studies at the University of San Francisco. "She's had a failure to launch among blacks, likely because of being connected to policing issues in the Black Lives Matter era."

Taylor adds that African American voters will come to her side if she succeeds on being the nominee, much as did in 2008 when there was a shift to Barack Obama’s candidacy once he started picking up primaries.

“If they feel she has a chance, they’ll move over,” he says. “Black people want to get Trump out of office. That’s the priority.”

Harris loves hand-to-hand politicking

Those who have worked alongside the senator during her California days caution that her big electoral milestones here were come-from-behind victories born out of a fierce love of hand-to-hand political combat – the very kind of combat that the presidential hopefuls will begin engaging in across New Hampshire and Iowa.

“In San Francisco, all politicians have to run the gantlet of countless groups and constituencies and somehow make their cases to all of them convincingly, a mirror of what happens in the primaries” says Nathan Ballard, a longtime Bay Area political operative who now runs The Press Shop media strategy firm.

“Our city here is just a great training ground for politicians, just look at Sen. Dianne Feinstein, Speaker Nancy Pelosi and now Gov. Gavin Newsom,” he says. “Politics is the sports of San Francisco. You have to be engaged, from the mansions of Pacific Heights to the inner city of Bayview-Hunters Point.”

Feinstein echoes that observation, noting that because of the diverse economic and cultural nature of the Bay Area, politicians have to connect with voters and build bridges across issues.

“That’s the only way to get things done, it’s not a place where you can sit behind a desk and be successful,” Feinstein says via an email to USA TODAY.

“California’s population of 40 million is larger than 21 states and Washington, D.C., combined,” she writes. “Because of that size, many of the challenges Sen. Harris faced at the local and state level weren’t unique to California, but rather representative of what the entire country is facing.”

One might think that San Francisco, a longtime bastion of Democratic values, would be a cakewalk for its candidates.

But political experts here say the opposite is true; that precisely because the city is represented by endless shades of blue, candidates for office have to work harder to address a range of concerns from both center- and far-left parts of the party.

“Political wars in San Francisco are all civil wars, and they’re the worst,” says Brian Brokaw, who ran Harris’ first campaign for attorney general back in 2009. “So it’s down to hand-to-hand combat, true retail politics, shaking as many hands as you can.”

Brokaw, who calls Harris “a tough, scrappy fighter who’s always counted out before she wins,” says much like clutch baseball hitters who can deliver home runs in the ninth inning, Harris “performs well in crunch time, just like the best prime time players. And she learned all that here.”

Critically for Harris’s presidential bid, which soon will test her across-the-aisle appeal, San Francisco demands that its politicians develop both a thick skin as well as deft political instincts, says Jason McDaniel, associate professor of political science at San Francisco State University.

“If you can get elected here, it is a product of your talent because it means you’ve succeeded in winning over the support of a wide range of people concerned about a wide range of issues,” he says.

McDaniel says broad coalition building is a hallmark of successful Bay Area politicians, as is the ability to connect directly with voters.

“If she can do well in Iowa, she’ll be formidable,” he says. “In San Francisco and later in California more broadly, she showed she has the ability to appeal to both a multiracial group but also, though her prosecutorial experience, with those who are look for that strength of character. She’s the real deal.”

Harris: Oakland born and bred

The story of Harris and her against-the-odds rise in state politics is increasingly familiar to national voters now as her presidential campaign intensifies.

Daughter of an Indian-born breast cancer scientist mother, Shyamala Gopalan, and Jamaican economics professor father, Donald Harris, Harris – and her younger sister Maya – grew up in a politically charged home in Oakland, singing in a Baptist choir and also attending a Hindu temple.

Her parents divorced when Harris was 7. When her mother was granted custody a few years later, the family of three moved to Canada for a university researcher position, and the sisters found themselves at a school for native French speakers.

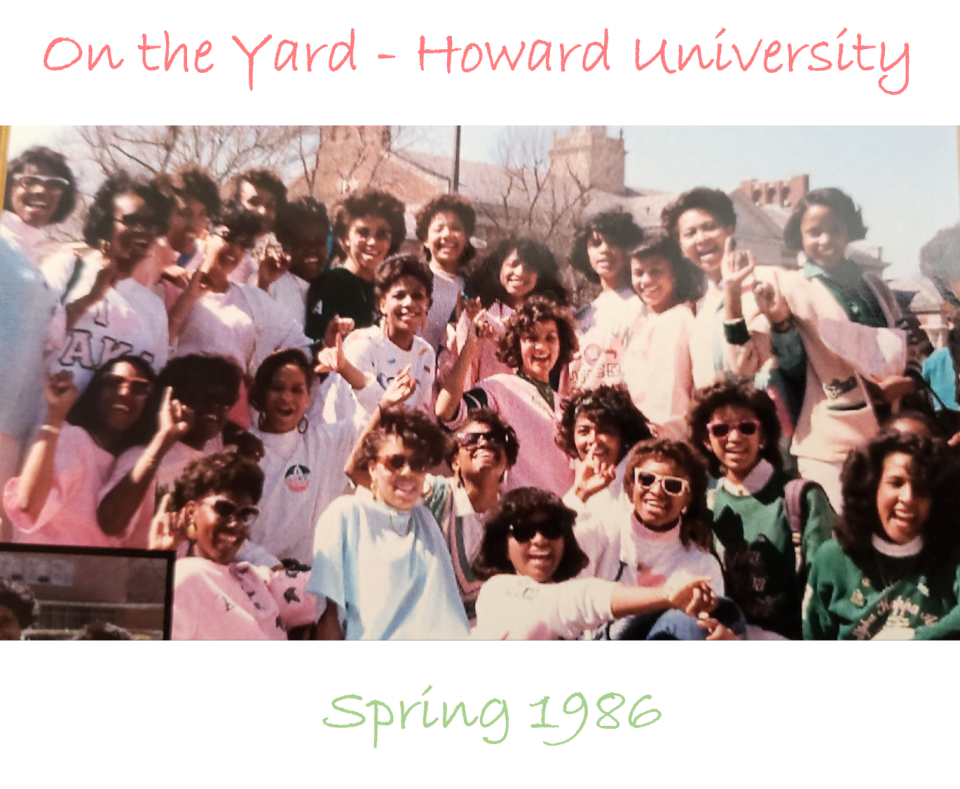

After graduating from historically black Howard University in Washington, D.C., Harris returned to San Francisco for her law degree from the University of California-Hastings College of Law. That led to a job as a prosecutor in nearby Alameda County, where her intense, and often controversial, passion for criminal justice reform took root.

A template was forged: That of an outsider – female and mixed-race – having to work hard to assimilate and appreciate a range of cultures and beliefs. It was a multicultural, multiperspective upbringing that would serve the future politician in Harris well.

“When she first announced she was running for DA, people started saying ‘You can’t do this,’ because you know, DA in San Francisco is a white man’s game,” says Amelia Ashley-Ward, publisher of the San Francisco Sun-Reporter, a 75-year-old publication focused on the African American community whose anniversary Harris helped celebrate with a visit this past spring.

Ashley-Ward – who considers Harris a “girlfriend’s girlfriend, someone who will laugh and cry with you, who always keeps a secret” – said her publication ended its longstanding support of the incumbent Hallinan, a progressive force in local politics, to endorse Harris.

She says the young candidate’s ability to garner support from a range of constituents instantly made her a force.

"Kamala can deal in the ‘hood, and she can work up top” with monied society donors, says Ashley-Ward, recalling Harris’ decision to put her campaign headquarters in the impoverished and often crime-challenged neighborhood of Bayview-Hunters Point. “We first met in 2000, and even then I was impressed how focused she was.”

Friends and former campaign staffers recall a tireless campaigner who would hop on and off cable cars pressing the flesh. She would set up on a street-corner with an ironing board as a desk, so as to be able to pack up and move on with pace.

Harris proudly drew on her Asian roots to garner support in an often divided Chinese American community, making sure a dragon was part of the victory parties.

Cookies, music and determination

When she won that first DA race, her small team moved into the DA’s office the very next day only to find that Hallinan’s cadre had removed all the furniture overnight.

“She worked out of a chair there, with a phone and no desk, for weeks, it didn’t stop her,” says Debbie Mesloh, a longtime Harris advisor who has worked on all of her campaigns.

What Mesloh witnessed over the next decade was a force of nature who balanced a fierce conviction about what was right – defiantly refusing to call for the death penalty for a man who shot a police officer in 2004, while Feinstein actively called for the opposite – with a mothering desire to keep her team of intimates happy.

In those early years as DA, Mesloh says, Harris would insist on an afternoon cookie break for staffers. But the die-hard foodie, who often would regale friends with new recipes, would also encourage them to join her for workouts.

Music also was an obvious passion, says her friend. Harris' favorite song was the one her mother adored, and it would play often in the office: “Oh Happy Day,” originally cut by Edwin Hawkins & the Northern California State Youth Choir.

Other staples included the music of reggae legend Bob Marley as well as the unique funk of Prince. Later, in 2016, when Prince died, Harris and her husband – Los Angeles attorney Doug Emhoff, "danced all night to his music in their backyard," says Mesloh.

And if it’s your birthday, “expect a call and a song from her,” Mesloh adds with a laugh. "She never forgets."

But that gentle side of Harris also has a steely doppelgänger. Some of that was inculcated into young Kamala early by her mother, who exposed her daughters to many of the freedom movements that were a hallmark of their late-‘60s youth in Oakland.

Newspaper publisher Ashley-Ward tells a story about Maya Harris introducing her sister after she won the DA race. “She said, ‘My mother would ask Kamala, what do you want?' and Kamala would shout back, “Fee-dom,” because she couldn’t say an R,’” says Ashley-Ward. “To me, it seems like she’s always looking for that. Freedom.”

That search to become her true self would require grit. Harris’ mother “instilled in Kamala not just a toughness, but also that desire to be a fighter for things that mattered, to not sit on the sidelines of life,” says Rebecca Prozan, a longtime San Francisco political operative who managed Harris’s DA campaign and now is chief of public policy and government relations for Google.

“We met way back in the ‘90s, and all I remember is she was very nice, very smart and really tough, she wouldn’t give up,” says Prozan.

When Prozan agreed to manage that first campaign, she didn’t hold out much hope for a win. “She was polling at 8%, and I thought, where’s the big earthquake going to come from to change things,” she recalls. “But Kamala just said, ‘Get me into a runoff, and I can win.’”

Harris immediately harnessed her network, which included connections to monied donors who were friends with Mayor Brown. She raised more than $200,000 – exceeding an agreed upon cap, which drew an apology from the Harris camp – and besieged voters with flyers listing her progressive credentials.

Mostly, she hammered the fact Hallinan’s office was a poorly run shop that needed diligent oversight to be effective. As she writes in her recently published memoir, “The Truths We Hold,” she wanted to bring “a professional operation” to the DA’s office.

“I believed the district attorney was undercutting the whole idea of what a progressive prosecutor could be,” Harris writes. “My vision of a progressive prosecutor was someone who used the power of the office with a sense of fairness, perspective, and experience” to hold criminals accountable while preventing crime in the first place.

When the local San Francisco Chronicle endorsed her, the tide turned.

Fazio tried another attack on Harris’ connections to Brown, which had led to her being appointed to lucrative state boards, but the move backfired and he lost ground.

Suddenly, that desired runoff loomed, and Harris picked up Fazio’s voters and beat Hallinan with a deft piece of political advertising: a direct-mail flyer that said simply “It’s time for a change,” followed by photos from a century filled with white, male district attorneys.

“Kamala Harris is all about breaking barriers and redefining what leadership looks like,” says former campaign advisor Newman. “Forever, it was considered impossible for a black woman from San Francisco to be elected statewide, especially as attorney general, a last bastion of largely Republican white men. But she did it.”

The Harris voters nationwide are getting to know as the presidential campaign ratchets up is the same woman who has startled, frustrated, delighted and captivated many Californians for the past two decades: a fearsome politician who loathes to take no for an answer.

“You’ll see her out there campaigning with that smile, she is like velvet in some ways, nice, loving and fun," says Newman. "But ask her opponents and even her staff, and they’ll tell you about the steel. You underestimate her at your own peril.”

Follow USA TODAY national writer @marcodellacava

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Can Kamala Harris beat Trump? California career shows she likes a fight