Kansas City Ferris wheel could be out-dazzled by what will soon lie below: Neon Alley

Nick Vedros has been fixated on a neon dream for six years. Set in the shadow of Interstate 35, where a white Ferris wheel has suddenly risen, he can finally see it taking shape.

On a recent Friday, Vedros, one of Kansas City’s most prominent commercial and art photographers, pulled his white Lexus SUV around road barriers to Pennway Point, a nearly 6-acre entertainment district under construction west of Union Station. Dust, kicked up in clouds by his tires, filled the air.

Vedros, age 70, with a gray goatee, hipster glasses and a cream beret worn backward, stepped from his car, as thrilled as anyone might be at the prospect of not just a wish, but also a promise soon to be fulfilled.

Countless drivers have, since September, already seen the 150-foot-tall Ferris wheel put up by Icon Experiences of Maryland and tentatively set to open around Thanksgiving. But fewer have a clearer vision than Vedros of one of the main attractions that will lie below. Slated to open as early as spring, it could be a draw that could literally make the LED-lit Ferris wheel look dull in comparison.

“It’s going to be a feast for the eyes,” Vedros said of the Lumi Neon Museum, the name, taken from the word “illumination,” for the outdoor museum of Kansas City signs that will stretch the width of the venue.

In 2017, when the Crick Camera Shop, at 7715 State Line Road, shut its doors after more than 70 years, Vedros — who in the 1960s bought some of his earliest cameras there as a teen — retrieved its neon sign, set against a sky blue background. He had no deep interest in neon signs at that time.

“Zero,” he said, “other than I thought it was kind of cool.”

But he felt the Crick sign was a piece of urban art and Kansas City history worth saving. He promised its owner he would one day find a way to once again light it up for the public. Today, Vedros and the volunteer members of the museum — founded as the nonprofit Save the KC Neon Inc. the same year Crick closed — have amassed and, in their own parlance, “rescued” 84 neon signs and fully restored 50 so far. The goal is to eventually have close to 100 on display at Pennway Point, where entry will be free to the public.

From tiny to gargantuan, the collection kept at Vedros’ Riverside home and secreted away in underground storage already creates a collage of Kansas City’s past written in glowing glass tubes of red, blue, pink, green and white lights.

Among just some of the neon signs: Cascone’s Grill, Savoy Barber Shop, Davey’s Uptown Rambler’s Club, Jennie’s Italian Restaurant, Winstead’s along with its rooftop pink and green spire, Turner’s Cyclery, Food Center, Harzfeld’s department store, the 4 Acre Motel, Stephenson’s Apple Farm Restaurant, Fun House Pizza & Pub, Broadway Hardware Co., Sears, Goodyear, Greyhound, the Capri Motel, Town Topic Hamburgers from a location before Crown Center was built, Kaluva’s department store, Harold Pener, Kelly’s Bakery, the I-70 Drive-In.

A recent donation, and in need of funds to restore: the towering sign from Stan’s A-Lotta-Stuff thrift store, which closed in KCK this summer.

Unable to recover an original Katz Drug Store sign with its iconic bow-tied black cat, the museum commissioned to rebuild one anew. The sign, whose creation was paid for by Jami and Fred Pryor of seminar fame, was unveiled in August, topped by a 6-foot-tall, 8-foot-wide cat’s head rotating 360 degrees.

“You see where that cone is, where that hole is dug?” Vedros said, walking through the construction site to what he said will be called Neon Alley. A steel beam to support some of the signs (the I-70 Drive-In sign alone weighs more than a ton) was set to go in.

“That’s where the Lumi sign is going to be,” Vedros said of the alley’s west end. “The I-70 sign will go here, at the entrance. It used to be 30 feet in the air. It’s going to be 10 feet in the air. People will go underneath like you’re going through a portal.”

He pointed up and away.

“The Stephenson’s sign will be up there, the Capri over there. Then, at the end” — he pointed east — “the Katz rotating sign will be right down there. This wall will be packed with signs. The other side will be packed with signs. This whole alley, it’s going to glow.”

The alley runs between two industrial buildings, one with a wood, barrel-roofed ceiling. The other, brick, steel and rectangular, open to the air like a courtyard, possibly with a retractable roof.

Two neon signs have already been hung, a Carter-Waters construction sign outside on the corrugated peak of one building. Atop an inside wall, single, cream-colored capital letters spell out “Downtown Kansas City.” When lit, its tubes will glow blue against the cream.

“These are our first signs that are up,” Vedros said. “They’re from the Kansas City Downtown Airport.”

A development timeline

Kansas City’s 3D Development, founded by Vince Bryant, is the main force behind Pennway Point. The company has found a market in new uses for historic buildings in the Crossroads Arts District south of downtown. Past successes include the renovation of the 10-story Thomas Corrigan Building built in 1921 at 1828 Walnut St. into the Corrigan Station office and restaurant complex. Another is the renovation of the 1921 Meriden Creamery Co. building, 2100 Central St., into The Creamery event space.

In 2017, Bryant purchased the The Kansas City Star’s former headquarters at 1729 Grand Blvd. for $12 million, intent on transforming it into a $95 million mixed-used development. The project, stalled under the pressures of COVID-19, is still underway.

Bryant said that, after purchasing the properties along I-35, he didn’t initially plan on an entertainment district.

“We purchased dramatically under-utilized and overlooked land in the middle of downtown,” Bryant wrote in an email to The Star. “Then we discovered the true character of these industrial buildings as we cleaned and cleared them. …

“Ultimately, we believe this site, that is, in some areas, 40 feet below I-35 and Pennway … was the perfect site for recreation hospitality in these incredible historic and industrial buildings.”

No exact dates have been announced, but Bryant laid out a tentative timeline.

In 2023, aiming to open before the end of the year: The KC Wheel at Pennway (Ferris is trademarked) perhaps before Thanksgiving; a snacks and beverage area; Pennway Putt mini-golf course.

The first 40 or so signs of the Lumi Neon Museum could be lit as early as spring. Bryant said that over the next 12 months the “recreation/ hospitality” area will be built in several phases.

TaleGate Park is planned as a 30,000-square-foot indoor/outdoor venue created in and around the former Funkouser Machinery Co. depot building. It is to house an upscale burger and steak restaurant, Beef & Bottle. Upstairs will be Funk House, a sports lounge that includes five “sky boxes” with views of TaleGate’s indoor stage and TaleGate Garden, with outdoor games.

Barrel Hall is to be located just to the south, inside the 6,000-square-foot former Pennway Oil Co. building with its wood-barreled roof. Inside will be a Boulevard Brewery Taproom, Chef J. BBQ, The Bull Creek Distillery, and Würstl (a Viennese sausage stand).

A taqueria is planned near the Ferris wheel, next to an outdoor beach volleyball area.

In 2025, Bryant said, the former four-story Carter-Waters Co., building at 2440 W. Pennway will house retail and office space. A newly built boutique hotel at 25th Street and Pennway is envisioned for late 2025 or early 2026.

“We believe Lumi will be a great destination draw by itself,” Bryant said.

‘Addicted to these signs’

For Vedros, Lumi has been a passion project.

“What happened is that I strangely got addicted to these signs over the years,” he said, and amazed by their staying power, designed to be outdoors in all weather.

“Those neon signs out there, if you leave them alone, they will continue to burn for another 100-years plus,” he said. “Some of them are still lit up after 80 years. And they can survive hail, which blew my mind.”

Vedros estimates he has spent thousands of hours as president of the nonprofit tracking down historic signs and, early on, spending thousands of dollars of his own money to purchase and restore them. Twenty people make up Lumi’s working staff, board of directors and advisers. None are paid.

When he isn’t searching for neon signs significant to Kansas City, Vedros said he is contacting with owners of businesses, writing them letters, trying to convince them to donate their signs. Most are donated by owners who want to see the history saved. What the museum can’t get donated, it tries to purchase.

Vedros emphasizes: Every penny the museum raises in outside donations goes to retrieving, restoring or repairing the signs. Individuals, families or companies can choose to sponsor a sign’s purchase and restoration and, when the sign is displayed with its history, receive due credit.

While some of their signs were still up when they found them, a great many were abandoned or unused, tossed behind sheds, broken or left to corrode.

“My pitch,” Vedros said, “is, ‘What’s your intention with this sign? Are you going to sell it? Are you going to get it hauled off?’ The big signs, nobody wants. They can’t put it in their man cave. I say, ‘We want to put your sign in our museum. We’ll pay for the safe removal of it. We’ll pay for the restoration. And we’re going to put it on display. Then we are going to keep it repaired and we’re going to light it up again.’

“’Your family will be able to go down there and see your sign with all these others. What could be better?’”

How neon lit up America

The idea isn’t new. Glendale, California, has its Museum of Neon Art. Cincinnati has the American Sign Museum. The Neon Boneyard, part of the Neon Museum of Las Vegas, draws thousands of visitors after dark to see the city’s glitzy history laid out and lit up in old marquees.

Neon — a colorless, odorless gas, number 10 on the periodic table of elements — was discovered in 1898. Placed in a vacuum tube and electrified, it emits a crisp crimson light. Argon gas produces blue. Other colors come from reactions with coatings on the inside of the tubes. Fifteen years after the gas’s discovery, a neon Cinzano sign advertising the vermouth illuminated Paris’ night sky.

In 1923, a sign reading “Packard” gleamed from a Los Angeles car dealership as the first neon sign in the United States. For the next 50 years, neon signs lit America, whether it was Kansas City or New York’s Times Square.

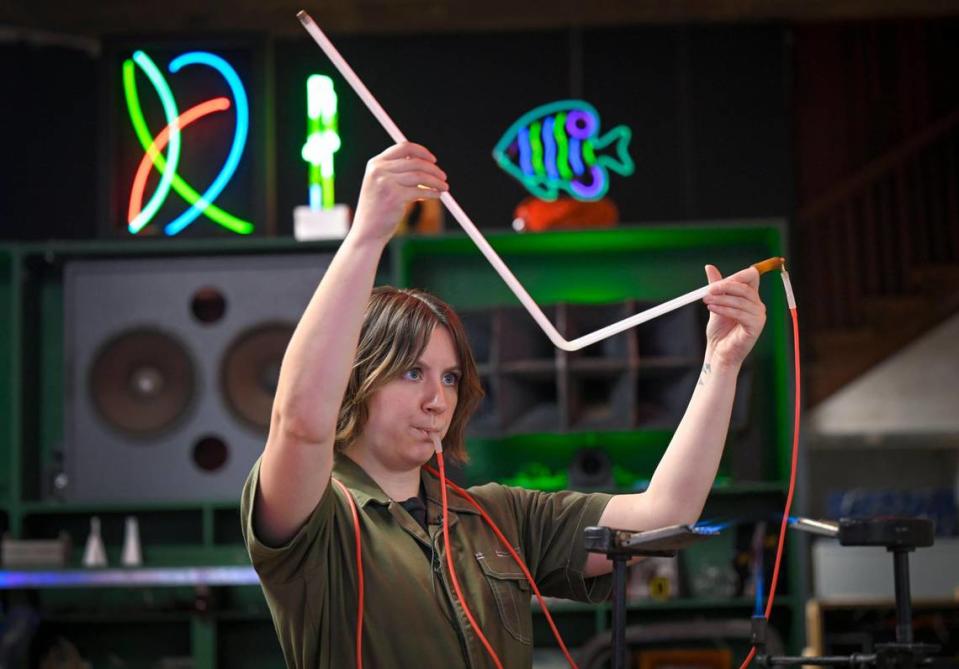

“I kind of think there is an ineffable quality to the light,” said Dylan Steinmetz, 38, who with sister Olivia Shelton, 31, co-own Element Ten, a neon sign and art company on Troost Avenue. Their father, Randy Steinmetz, who works alongside them, has been making and working on neon signs for more than 40 years, including the Western Auto sign in the Crossroads.

Olivia speaks of neon’s “campfire effect.”

“There’s something about a campfire that you want to gather around, you want to gaze into it. Neon has a similar feeling,” she said.

Dylan went further. “It’s a unique source of light,” he said. “Normally, we’re producing light to cast light onto something. This switches that around, where you’re encouraged to look into the light. It’s the focal point. We’re drawing in light in three dimensions, which is pretty fantastic. There is nothing else that really does that.”

A Turner Music Co. sign, Broadway Hardware, Greyhound, Goodyear, the Lumi sign: Element Ten worked on them all, including collaborating with Fossil Forge, a sign and graphic display company in Lee’s Summit that recreated the Katz drugstore sign.

“Nick probably started bringing things in around 2019, before the pandemic,” Dylan said of Vedros. “I’m really excited that this is outdoors. It would be a shame if it was tucked away behind walls.”

Kansas City’s neon community

Vedros said that Lumi and its mission have opened him up to a tight community of neon and display sign artists in and around Kansas City: the Steinmetz family at Element Ten, Dave Eames and Ben Wine at Fossil Forge (Wine is now on the board of Lumi; Eames is a former Kansas City Star artist), Greg Garnett at Gama Neon LLC in Kansas City; Curtis Shadd and Jason Yeager at Midwest Sign Co., Jason Walker at JWW Fine Art in Olathe.

“Oh, my God,” said Eames of Fossil Forge, “we are beyond excited. I mean we live and die vintage signage and Kansas City history.“

He spoke of how, beginning in the late 1960s, neon signs fell out of favor.

“It really took on a stigma,” he said and became synonymous with strip joints and liquor stores. Many municipalities began to ban neon signs.

“That was really unfair,” Eames said. “There were other forces at work, including the plastics industry and fluorescent bulbs and all this new technology that arrived after World War II. There was incredible pressure to outlaw these old signage statements. And that’s what happened.”

Including in Lee’s Summit. Then Eames and Wine stepped before the city council to make a case for the beauty of the signs and to repeal an ordinance that banned them from the city’s historic downtown. The area now has more than 50 on display.

“We love how these signs offer such memories and nostalgia for people,” Eames said of the Lumi signs. “These sorts of advertising icons used to stand along our highways and byways. It’s a beautiful combination of graphic design materials like glass and steel and porcelain. Then you layer that in with memories people have of these places … you’ve got a mixture that is going to be crazily evocative to most people.”

Vedros said he can hardly drive through Kansas City without looking for signs to bring to the outdoor museum, if not soon, perhaps in the future. He said Seiden’s Furs at Ninth Street and Broadway has one that he’d like to procure, although he thinks the owners may want to keep it.

At Ninth and Prospect, a neon Hum-Dinger hamburger drive-in sign with a smiling bow-tied server carrying a platter of food stands alongside the red and white striped building.

“I’ve been in contact with the owner,” Vedros said. “We need this classic.”