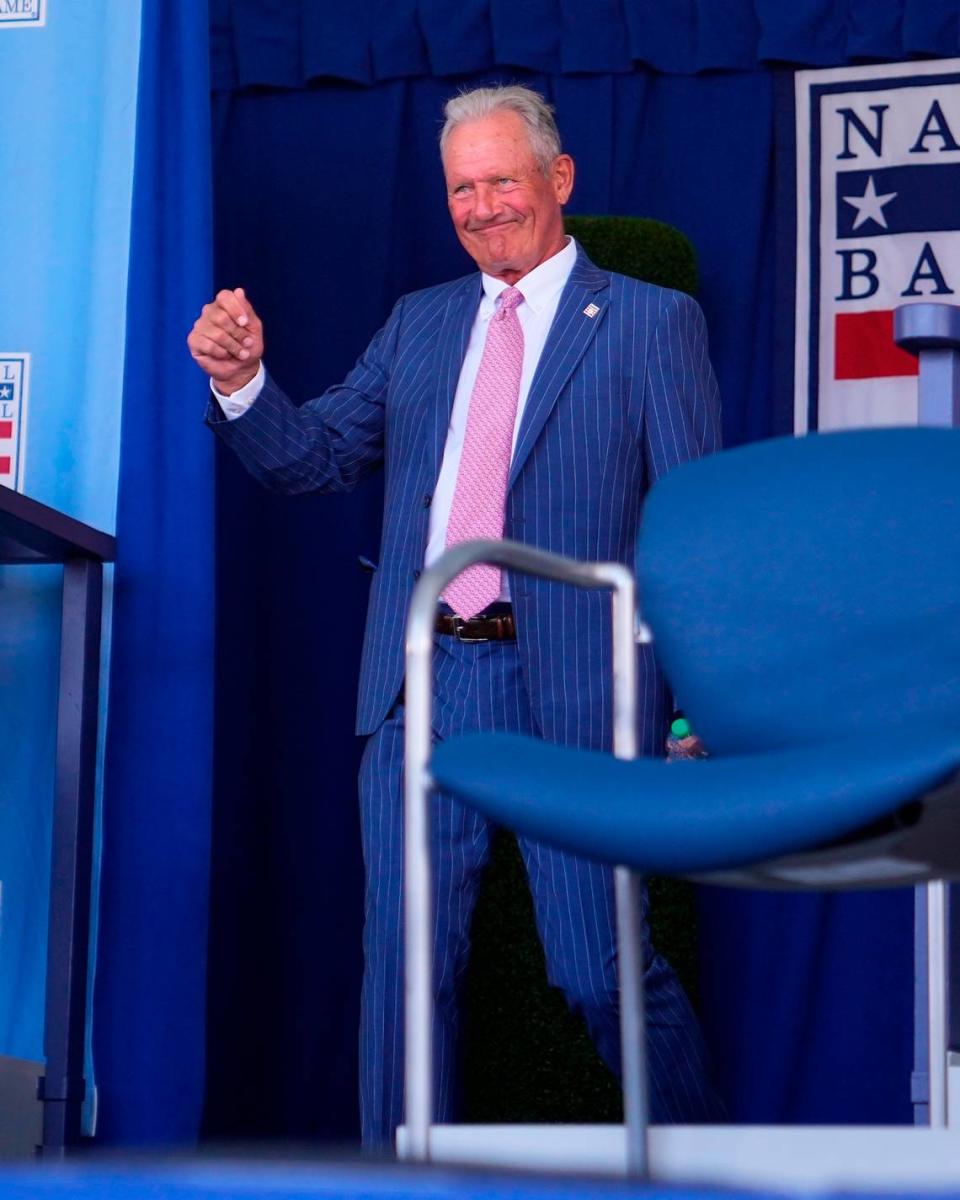

Kansas City Royals icon George Brett celebrates journey & legacy 50 years after call-up

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Grilling burgers with his roommates early on an August afternoon 50 years ago, George Brett was puzzled by the arrival of manager Harry Malmberg at their apartment on 84th and Q streets in Omaha.

At first, he wondered what trouble he and/or his Omaha Royals (now Storm Chasers) teammates, Mark Littell and Buck Martinez, were in. But Mahlmberg quickly dispelled that.

“‘Congratulations — you’re going to the big leagues,’” Malmberg said.

With that, Brett and Martinez turned to congratulate Littell, the presumptive call-up … only to be instantly corrected:

It was the 20-year-old Brett — who never hit .300 in the minor leagues and was in his first Triple-A season — being summoned to the parent club to fill in for injured third baseman Paul Schaal.

With the flight to Chicago for that night’s game just hours away, Brett scrambled to pack and gather his gear at the stadium. Told he wouldn’t be in the lineup that night at Comiskey Park, Brett tried to compose himself on the plane even as his mind was “going 100 miles an hour.”

Safe to say there wasn’t much fanfare over the kid who was only to be up a few weeks in place of Schaal, who had suffered a sprained ankle.

No one greeted him at the airport. Or, for that matter, at the stadium, where he walked in among fans lugging his suitcase and equipment bag and needed help just to find the clubhouse.

He was disoriented, nervous and even scared as he arrived with batting practice coming to an end.

And that was before the 29th pick overall in the 1971 MLB draft discovered he actually was in the lineup, batting eighth, on Aug. 2, 1973.

“Your dreams have come true,” he said, “but your mind is just racing.”

Driven as he was in so many ways, including by the cruelty of an abusive father, Jack, Brett still had no real notion of how he fit or even if he belonged. And the same ever-present specter of Jack Brett that propelled him also made him “scared to death before every game.”

So who could know what was to come, especially when he got demoted a few weeks later and started the next season back in Omaha.

“You have no idea how good you’re going to get, how good you’re going to be or how long you’re going to play,” Brett said in a recent interview at his Mission Hills home. “You have no idea the accolades you’re going to get. You have no idea.

“You just go out and play.”

So he did.

Like few before or since.

The montage

Despite some early struggles and hitches, that night bookended a career that would culminate 20 years later with ceremonial moments befitting the greatest Royal — the only franchise player to have spent his entire career here to be honored in the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

It would end at home with a forever stirring and iconic portrait of his love of the game: spontaneously kneeling to kiss home plate, a nod to his friend and baseball great Hank Bauer, to punctuate a rousing ovation as he was carted around the field.

Days later in Texas for the last at-bat of his last game, Rangers catcher Pudge Rodriguez put his arm around him and told him Tom Henke was going to throw only fastballs and wanted him to get a hit.

With players from both teams standing in front of the dugout and an ovation from the crowd, Brett said, “It was hard to keep a dry eye.”

But he singled up the middle for the 3,154th and final hit of his career, a staggering number that began with a broken-bat “jam shot” off Stan Bahnsen that 1973 night in Chicago.

In between?

Start the reel like this:

“I would say at the beginning of it, the montage should be me playing third base, saying, ‘Don’t hit it to me,’” he said. “Or me being on the on- deck circle and Sparky Lyle or (other tough left-handers are) in the bullpen … and I’m on the on-deck circle, and I say, ‘God, I hope they don’t bring him in to face me.’”

Flash forward, then, to Brett on third saying, “Hit me the (darned) ball. Or me on the on-deck circle, and you see Randy Johnson pitching in the bullpen, and I say, “I hope they bring that son of a bitch in to pitch to me, because I’m going to (damn well) beat him.”

Because at a certain point or baseline of talent, Brett wants you to know, it’s all about mindset.

“You have to have success first to really believe it, you know what I mean?” he said. “Yeah, you just can’t trick yourself.

“I think in the beginning you’re tricking yourself. But then all of a sudden, by putting yourself in the right frame of mind, you put yourself in a position to succeed, and then you start having some success.

“So then once you have success, it’s easier to believe it.”

With a pause, he added, “I’ve never really thought of it like that before.” But it all seems so clear now.

And that underpinning led to so much to cherish — and all the more so for Kansas City since Brett, embracing the advice of older brother Ken, made his home here and never left.

“Where would I want to go?” he said, noting the Royals were a perennial playoff team into the mid-1980s and adding, “I am so glad I stayed. So glad. And to be, you know, a Southern California guy growing up a half a mile from the frickin’ ocean. And now to live in Kansas City for 50 frickin’ years.

“A lot of people don’t believe I still live here. But a lot of people that say that have never been here.”

The legacy

Brett was a vital part of making this the place to be for baseball from the mid-1970s to the mid-1980s, in particular, and to some degree over the course of his career overall.

In those first 20 years here, he became the first player in MLB history to win batting titles in three different decades (1976, 1980 and 1990).

He became one of only two players (along with Tony Gwynn) to hit .390 or more since Ted Williams became the last .400 hitter in 1941 — a fascinating tale in itself.

And Brett, the 1980 American League MVP, became the first player to have at least 3,000 hits, 300 homers, 600 doubles, 100 triples and 200 stolen bases. He was a 13-time All-Star selection with a .350 career postseason average.

And, yes, he also became well-known for the hemorrhoid issue during the 1980 World Series and for the Pine Tar Game of 40 years ago — and the fury uncorked by the petty insinuation he somehow was cheating to take a competitive advantage.

(The rule had been made simply to minimize the number of balls being thrown out because of the gunked-up stains of pine tar.)

He remains proud of standing up for himself, unhinged as it appeared, because he couldn’t tolerate the assertion he was swindling the game.

But when Brett reflects on what mattered most to him, the first thing he brings up is winning the 1985 World Series.

“I don’t care who you were in that locker room,” he said. “If you were the guy that unpacked the bags or shined the shoes or cleaned the toilets or did the laundry, you had this exact same feeling as I did. …

“Everybody had the same exact feeling. That would probably be No. 1 because it wasn’t a one-man celebration.”

Number two is the spine-tingling three-run homer off Goose Gossage into the third tier at Yankee Stadium to pave the way to the 1980 World Series — past, at last, the Yankee nemesis.

Third, he reckons, was 3,000 hits as a “testament of longevity and consistency.”

Fourth, well, “there’s so many things that happened in the career.” But he figures it was that last home game that delivered the sort of love and appreciation that few could ever know.

The fire inside

Brett led the 1993 team in RBIs with 75 and hit .266 with 19 home runs. Even at 40, he could have kept playing.

But the career .305 hitter had lost something fundamental: the mechanism inside that was the difference between just doing a job and being on fire about it.

All of a sudden, he didn’t get goosebumps with a big hit. He didn’t get mad when he did something wrong or “bad,” as he put it. He didn’t like being relegated to designated hitter so often, and games felt like they were taking five hours.

He found it hard to relate to the younger players who would “go to their rooms and play Nintendo golf” after games when he still wanted to go out for some beers and a sandwich.

All of that was part of why, instead of showing up at the park by 2:30 p.m. at the latest for night games, he’d find himself napping until 3 and needing to be prodded to go by his wife, Leslie.

“That’s when I knew,” the father of three said, “it was time to retire.”

That might have been evident to anyone feeling that way.

But it was particularly glaring to a man whose combination of intensity and joy for the game were all the difference in a career that left him now, at what he calls a “mind-boggling” 70 years old, with two bad shoulders and two bum knees but untroubled by that and happy to be able to play golf.

It was that drive inside, after all, that made him reach back for more after he finished 1973 hitting .125 with the Royals (5 for 40) and found himself at times not even wanting to play because his sporadic starts left him drained of confidence.

He started 1974 back in Omaha before returning to Kansas City with the trade of Schaal … and sputtering until he received the well-documented tutelage of renowned hitting coach Charlie Lau.

What began with Lau chastising him for making no adjustments and never seeking his help led to Brett becoming a devotee.

“Charlie was honest with me,” Brett said, “and I gave him my heart and soul.”

Picking up a nearby bat in his home office, Brett stood and demonstrated how Lau moved him off the plate and flattened his swing and taught him to look the ball all the way into the catcher’s glove.

And how he taught him about rhythm and taking his top hand off after contact to swing through the ball better and creating line drives by keeping the bat in the zone longer — not trying to create launch angle, a contemporary fixation that Brett detests.

When he’s asked if he would have been a good player without Lau, Brett believes so. But he quickly adds, “As good? No. How good? I don’t know.”

Making his own way

For entirely different reasons, it’s a question Brett also thinks about in the context of his father.

Thirty-one years after his death at 68, Brett immediately brings him up when he considers where he got his drive.

Just as immediately, he calls him profane names.

“He was just a mean guy. Real mean,” said Brett, who called his mother, Ethel, the glue of the family.

Jack Brett was wounded “pretty bad” serving in World War II, the youngest of his four sons recalled, and he had a bad leg.

But the war, Brett said, ruefully, “didn’t hurt his fists.”

It didn’t keep him from doing a lot of things to his boys, as artfully documented in Sam Mellinger’s 2016 Father’s Day column about the dynamics between them.

And it didn’t keep him from calling George up during a slump in his remarkable career and screaming at him.

Or from cursing at him when he came home at Thanksgiving in 1980 for not managing the five more hits that would have put him at .400.

“That’s life,” Brett said. “But you know what? If he was different, maybe I wouldn’t have had that drive? Who knows?”

Whether despite or in some ways because of that, though, Brett made his own life and name and fame and fortune through a journey of many pivot points — including the career that started in earnest but inauspiciously a half century ago next week.

“Little did I know,” he said.