‘Kansas City is so ugly’: How our town leveled up from its dirty, hilly, homely past

Local folks like to boast about the beauty of Kansas City, with its boulevard system to rival Paris’ and nearly as many fountains as Rome.

But most people probably don’t realize that until the late 19th century, Kansas City was downright homely.

In the 1858 book “Annals of the City of Kansas,” C.C. Spalding wrote, “It is very true that the topographical view of our city, at first sight, is anything but inviting to the vision. Bluffs, ridges and ravines seem to be a poor and costly place to build a city.”

So how did Kansas City turn from an ugly duckling into a beautiful swan?

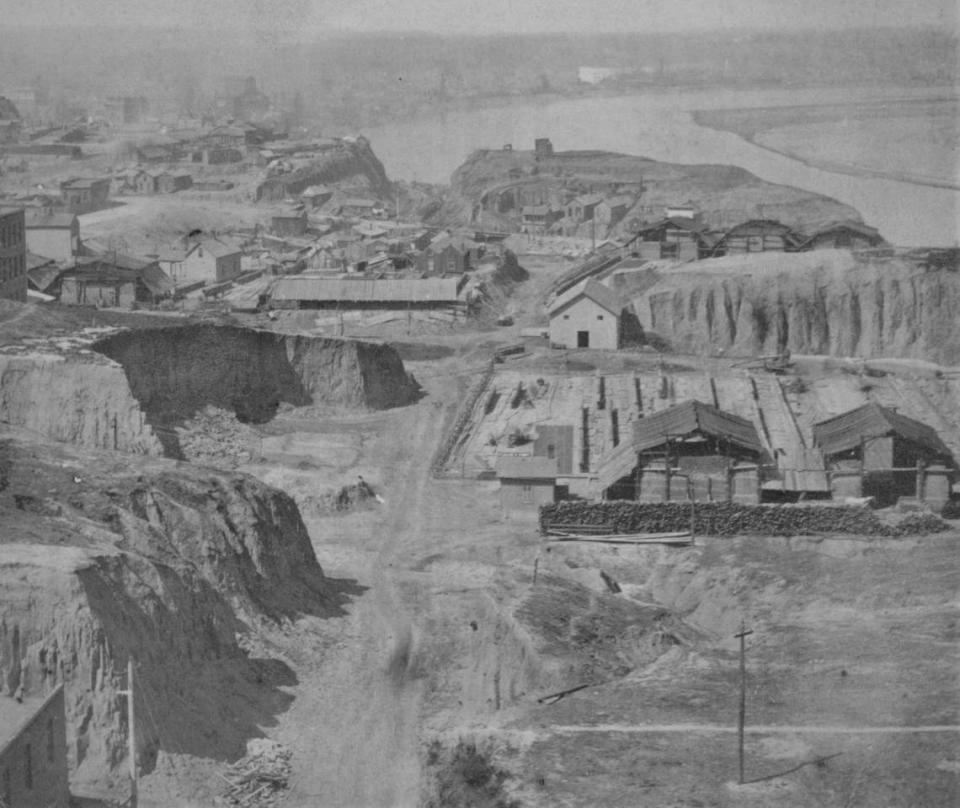

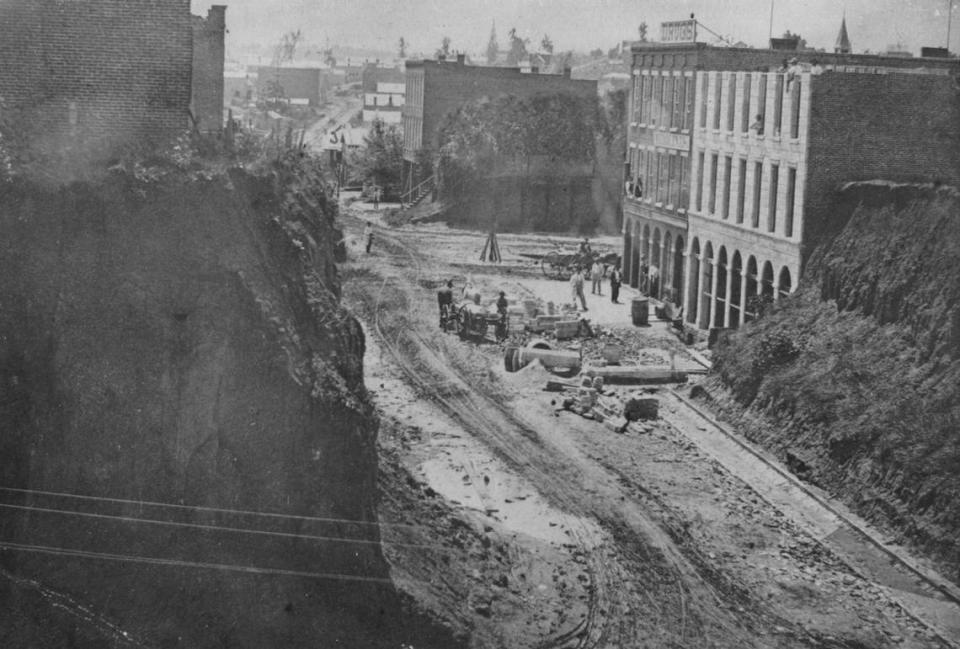

The key was getting rid of those bluffs, ridges and ravines by leveling the area south of the riverfront. The process took more than a half-century, and for much of that time the city was a carved-up mess.

Reader David Buck wondered about those nascent days of Kansas City and contacted KCQ, The Star’s ongoing series with the Kansas City Public Library that answers readers’ questions about our region. His query:

“Hemingway called Kansas City the city of planed hills, it is said, and he actually wrote about the hills. There are dramatic images of streets excavated to ease the path from the bluffs to the river. But what made the area so hilly, and what was life like before the hills were leveled?”

Ernest Hemingway, who spent 6 1/2 months working for The Star in 1917 and 1918, mentioned the area’s topography in “God Rest You Merry, Gentlemen.” The 1925 short story set in Kansas City began:

“In those days the distances were all very different, the dirt blew off the hills that now have been cut down, and Kansas City was very like Constantinople.”

Constantinople, which became Istanbul in 1930, was known as the City on the Seven Hills. Kansas City, on the other hand, eliminated most of its hills to produce the relatively flat downtown we now enjoy.

KCQ addressed the origins of Kansas City’s topography in 2021, discussing the Pennsylvanian Age, an inland ocean and the resulting layers of limestone that created the bluffs that stood as a barrier to the city’s growth.

To complement that earlier KCQ, we take a closer look at the period when downtown Kansas City was a series of carved-through hills and residents could find themselves living next to a street one day and at the edge of a cliff the next.

‘A little foul’

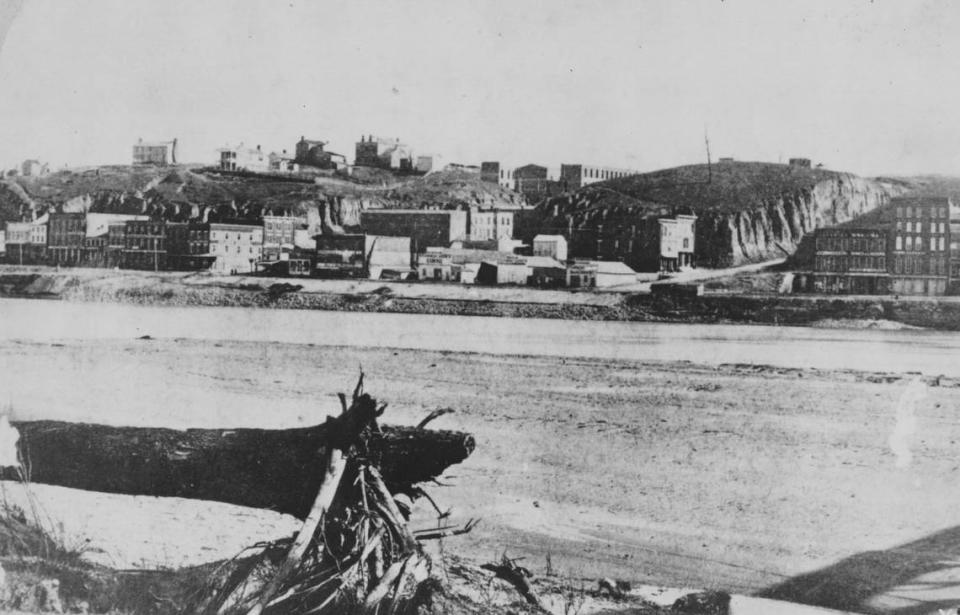

Thirty years after Missouri gained statehood in 1821, what would become Kansas City remained little more than a few buildings on the riverfront abutting bluffs that towered as high as 100 feet.

“People hesitated to move southward of the bluffs, where the land presented only a succession of hills and ravines, ponds and springs, rocky buttes and timbered knolls or wastes where nothing more inviting than stumps was to be seen,” a 1905 Star story said. “It was not a land of promise. No one, in those days, believed that the town would ever become a place of importance.”

Visitors to the area were even less diplomatic.

John Herron, who worked on several projects related to Kansas City history while a professor and administrator at University of Missouri-Kansas City for 17 years before becoming director of the Kansas City Public Library in 2020, told The Star: “What is true is how universally, almost every visitor account is like, ‘Oh, good grief, Kansas City is so ugly.’”

It wasn’t merely the city’s appearance that was off-putting. The sewage system, such as it was, also contributed to the area’s lack of curb appeal.

“You would just dump your waste, whether it be human waste from your house or waste from whatever little warehouse you had, and it just goes into these gullies,” Herron said. “It was a really unusual looking city that also was a little foul.

“What’s not perfectly understood is just how crammed and jumbled early Kansas City was. Because it’s basically the south bank of the Missouri River to the limestone bluffs. … In this tiny little space, you had houses that were scattered against the bluffs. You had streets that were narrow and jumbled. You had livestock that were wandering the streets. You had an occasional kind of junky warehouse that would populate the levy.”

Meanwhile, venturing from Westport Landing and its natural wharf on the riverfront to the burgeoning town of Westport beyond the bluffs included its own challenges. It meant maneuvering through the gorges and up steep slopes along passageways barely wide enough for a horse and wagon.

A few houses and businesses popped up along the way, but Kansas City’s businessmen knew what had to happen for there to be any real growth.

“These are people who are developing businesses, and to them figuring out a way to make the site function for business was their primary concern,” Herron said.

“It’s a very intensive but simple process of cutting the hills, throwing the dirt into the ravines, and the city slowly smooths itself up as it grows south. And you can literally watch the city as it’s carved out.”

But it didn’t happen overnight — except when it did.

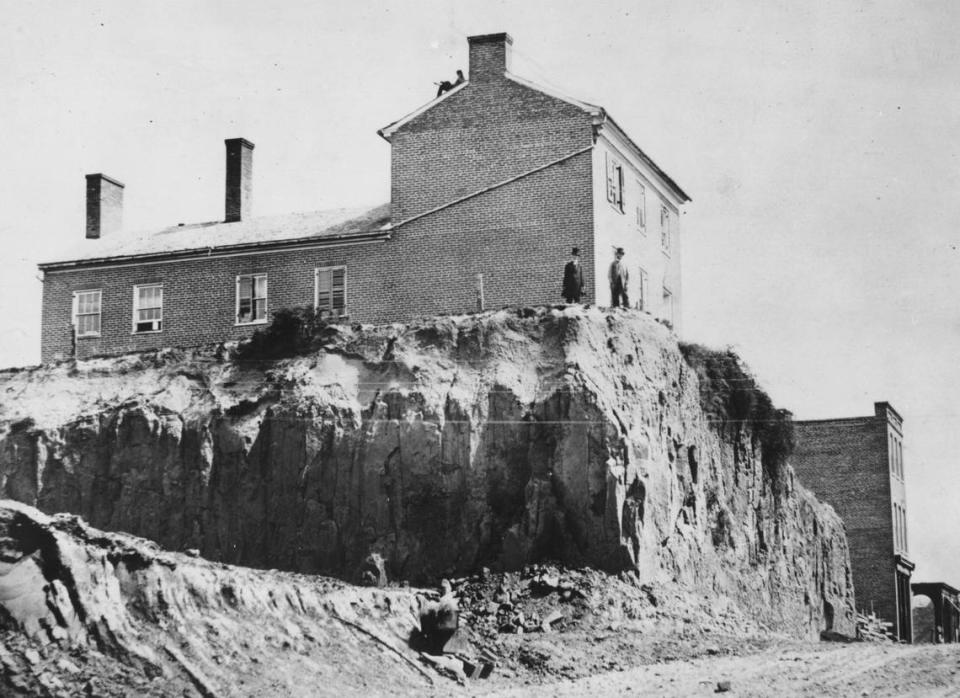

Dr. T.B. Lester owned a cottage with a front porch a few steps from Main Street between Second and Third streets. When he returned from a trip late one evening, he found his home nearly 20 feet above Main.

Lester decided to build a second level to the house, but he placed it below the original structure rather than on top of it.

It wasn’t long before the city fathers decided Main was still too steep and narrow, so they ordered another cut. Lester’s house again wound up 20 feet or so above the street, and he again added a ground floor underneath it.

“It was certainly a spectacle,” John Donnelly, an ex-city engineer, told The Star in 1905. “It was a funny thing to see that story, the dwelling above it, and, still higher up, the little cottage with the porch projecting over the street.”

Residents had no say in the matter, even when their property was damaged. The city simply charged ahead with the cutting, offering no condemnation proceedings and usually no compensation to homeowners.

The Kansas City Times noted one exception in 1977:

“One citizen did obtain $2,825 damages after he returned from a trip one night unaware that his street had been graded in his absence, leaving a precipitous drop without guard rail or warning light. He fell 15 feet, breaking an arm.”

Other homeowners just enjoyed the view.

“Jesse Riddlebarger, merchant, had an expensive house on the bluff, not far from Pearl Street, near the river,” The Star wrote in 1905. “… Riddlebarger’s house was sixty feet above grade, and no one could convince him that it was too high up.”

Making a Case

When Theodore Case arrived in Kansas City in 1857 with a degree from Sterling College of Medicine in Columbus, Ohio, the Missouri town was the very essence of the Wild West: murders, street fights, prostitutes and more.

Horace Greeley, of “Go west, young man” fame, would say two years later that Kansas City was a “malignant stronghold of persecution and violence.”

Case wasn’t scared off, however. He practiced law as well as medicine here and later was postmaster. He also became a local historian, writing about the town he found in 1857:

“Only one street — Market, which later became Grand Avenue — was cut through to the levee from the south and could be used for business locations; on the rest the grades were still too steep, and the streets oppressively narrow. Smithies, saloons and a few stores straggled along Market Street, ending in what seems to have been a little slum inhabited by some Irish settlers.

“South of the crest of the bluffs, more shops and saloons were joined by residences. … A deep ravine meandered diagonally across the whole townsite, debouching in the river near the foot of Market Street. It was bridged only where it crossed Main and Market, and at the latter place the crossing was ramshackle and dangerous.”

Dangerous indeed. According to The Star in 1987, Case had said, “It was a standing news item that several persons had been killed in Kansas City by falling off some of the bluffs in the main part of the city onto the tops of four-story buildings.”

Case eventually witnessed the leveling of Kansas City.

“If a hill was in the way, they cut it down,” he wrote. “If a ravine interfered, they threw the hill into it.”

Most of the early leveling work was done by 300 Irish immigrants who were brought here by the Rev. Bernard Donnelly, Kansas City’s first Roman Catholic priest. They all came from the province of Connaught (or Connacht) in western Ireland, and the area near Sixth and Broadway where they settled became known as Connaught-town.

From a modern-day perspective, the city’s transformation is hard to imagine — especially given the scene before and during all the leveling.

“When we say, ‘Oh yeah, there were bluffs that were 40, 50, 60, by some contemporary accounts even as much as 100 feet high,’ it’s really hard for people to picture in their mind’s eye,” Herron said. “It’s hard to envision what early Kansas City looked like, given how dramatically transformed the downtown landscape was.”

If that transformation had not taken place when it did, who knows what would have become of our little “malignant stronghold of persecution and violence”?

“The fact that Kansas City becomes the city of choice in this region was not assured,” Herron said. “You hear lots of references to Kansas City as Gully Town. These were intended as slurs or slights. So if you were in St. Joseph, you would say, ‘Why would you ever want to do business in Gully Town?’

“Certainly, had Kansas City not in essence leveled itself out, it wouldn’t have become the commercial center that it is.”