Kansas police searched their car without a warrant, and they lost custody of their son

It’s been more than two years since Claudia Astudillo Aguirre lost custody of her child.

Garden City Police searched her family’s car without their consent, resulting in criminal charges that were later dropped. But she’s still grappling with the fallout from the search after the loss of precious years with her infant son, who remains in the foster care system.

Her experience represents what many attorneys say is the most common form of Fourth Amendment rights violations – the warrantless vehicle search.

Traffic stops or welfare checks at cars can lead to investigations if an officer sees something in a vehicle they believe is suspicious or smells drugs or alcohol. But an officer’s decision to search a car or extend a stop can quickly cross a line if there is insufficient evidence or a lack of consent.

In Astudillo Aguirre’s case, the 46-year-old immigrant from Mexico was sitting in the back seat of her family’s parked car in October 2021 with her son, her partner Elliot Schuckman and a friend when Officer Andrew Babin approached their car.

Babin saw a baseball bat in the car between the two front seats and asked Schuckman to get out. He patted down Schuckman, didn’t find anything illegal and asked for permission to search the car. Schuckman said no.

“He had no business even approaching our car that day,” Schuckman said.

A second officer, Stephanie Camarena, arrived and patted down Astudillo Aguirre who cried in fear. Camarena later testified in court that she found a bag of what she believed to be methamphetamine, but Astudillo Aguirre denied the bag contained drugs.

Then, without consent, the officers searched the car and allegedly found more drugs.

The Garden City Police Department declined to release dashboard or body camera footage from the search.

The officers arrested the couple and took their young son into custody. Astudillo Aguirre was charged with aggravated endangering a child and two drug crimes. Schuckman was also prosecuted.

After Astudillo Aguirre’s attorney filed a 10-page motion to suppress the evidence on the grounds that police lacked probable cause to search her in the first place, prosecutors dropped their case in October 2022. Two charges against Schuckman were also dismissed but he pleaded guilty to one of the drug charges.

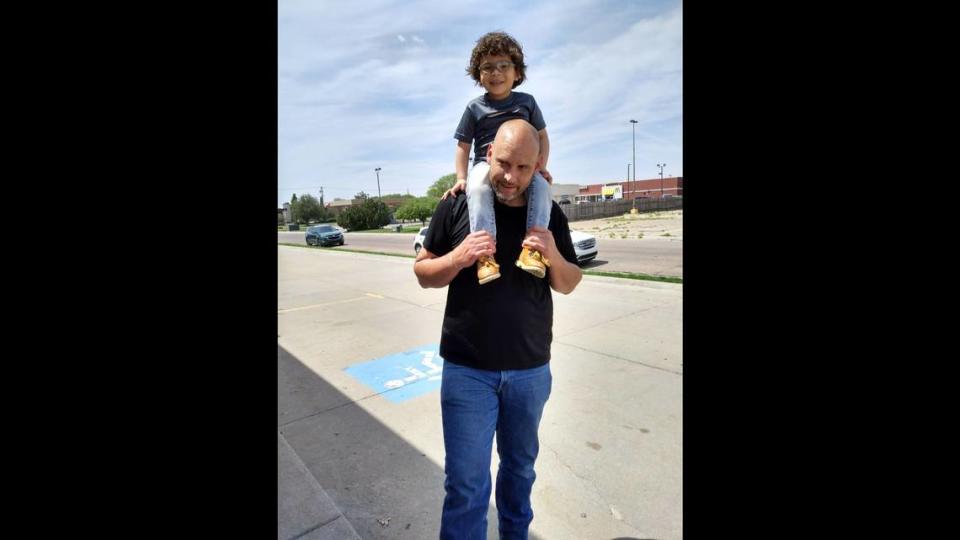

In the months — and years — that have followed the search, the couple has not regained custody of their son, Victor. Instead he is in the foster care system and they are allowed visitation for one hour a week.

“I want to be with my son,” Astudillo Aguirre said. “When they take him, he was baby. Now, he’s really big.”

She and Schuckman are suing the police department in federal court. Citing the litigation, Garden City police officials declined to answer questions about any Fourth Amendment training officers undergo or the 2021 arrest.

Babin left the department in April, according to the Kansas Commission on Peace Officers’ Standards and Training, which certifies officers. Camarena is still with the department.

The couple had a custody hearing on Dec. 5, but a resolution isn’t expected until February. The Kansas Department for Children and Families said it is not allowed to provide specific case information.

Cole Hawver, a Junction City-based public defender, said he is most likely to find possible Fourth Amendment violations in traffic stops. When he sees these cases, he’s asking himself a series of questions.

“You’re always looking, was the stop legit to begin with, was there actually a traffic infraction, are they extending the stop in violation of the Fourth Amendment in order to buy time for their investigation?” Hawver said.

Pottawatomie County Attorney Sherri Schuck said motions to suppress are rare in her jurisdiction but they’re most likely to be disputes to evidence obtained during a traffic stop.

Each case is situational and it’s a fine line that determines whether an officer has enough cause to search. If there is not enough cause, it’s another fine line to determine whether a reasonable person would know they’re engaged in a voluntary interaction and are free to leave.

For Astudillo Aguirre, police testified they stopped to check their car because it was suspicious.

The apartments they were parked in front of were in an “area known for drug traffic as well as stolen property traffic,” Babin testified in Finney County District Court.

But Astudillo Aguirre’s attorney argued that the officers lacked any probable cause to pat down the couple or search the vehicle.

“Officer Babin had no reasonable suspicion to stop the vehicle,” attorney Kelly Premer Chavez wrote in a motion to suppress. “Officer Camarena had no cause to search the Defendant and there was no probable cause to conduct a search of the vehicle.”

Vehicle stops across the state came under fire when the ACLU of Kansas sued over what it alleged were unconstitutional practices in 2019.

In a scathing ruling issued earlier this year, a federal judge found the Kansas Highway Patrol had engaged in a pattern of Fourth Amendment violations during vehicle searches through the use of the “Kansas two-step.”

In the practice, officers would take a couple of steps away from a car during a traffic stop before returning to start a “voluntary” interaction.

When police officers stop a car they have put the driver in temporary custody. Once the traffic stop has concluded they are supposed to let that driver leave unless they have probable cause or reasonable suspicion to believe a crime has been committed or the driver grants voluntary consent to extend the interaction.

But for many motorists, the transition to a voluntary stop where they could leave was not clear.

Lauren Bonds, executive director of the National Police Accountability Project who was legal director at the ACLU of Kansas when the two-step lawsuit was filed, said she found the highway patrol was not the only jurisdiction in Kansas that used the strategy.

“Officers are often encouraged to kind of be aggressive in finding ways to extend detention and finding ways to find a basis to conduct a warrantless search,” Bonds said.

In her ruling against the Kansas Highway Patrol, Judge Kathryn Vratil noted that troopers deliberately capitalized on this confusion in traffic stops that turned to drug investigations.

“KHP training materials acknowledge that pretextual policing strategies depend on ignorant, timid drivers, and joke that more informed and assertive drivers might identify themselves with bumper stickers that say, ‘WARNING! OCCUPANT KNOWS THEIR 4TH AMENDMENT RIGHTS,’” Vratil wrote in a sub note.

The Star’s Jonathan Shorman contributed to this report.