Kansas schools fear Evergy rate hikes, higher bills will harm teacher recruitment

Kansas school districts are warning Evergy’s plan to raise electric rates will saddle them with painful higher costs that harm their ability to recruit and retain teachers.

Wichita Public Schools USD 259, the state’s largest district, filed documents with the Kansas Corporation Commission decrying the proposed increases and alleging they could lead to larger class sizes. De Soto USD 232 told The Star that its projected additional electric costs could pay for three or four teachers.

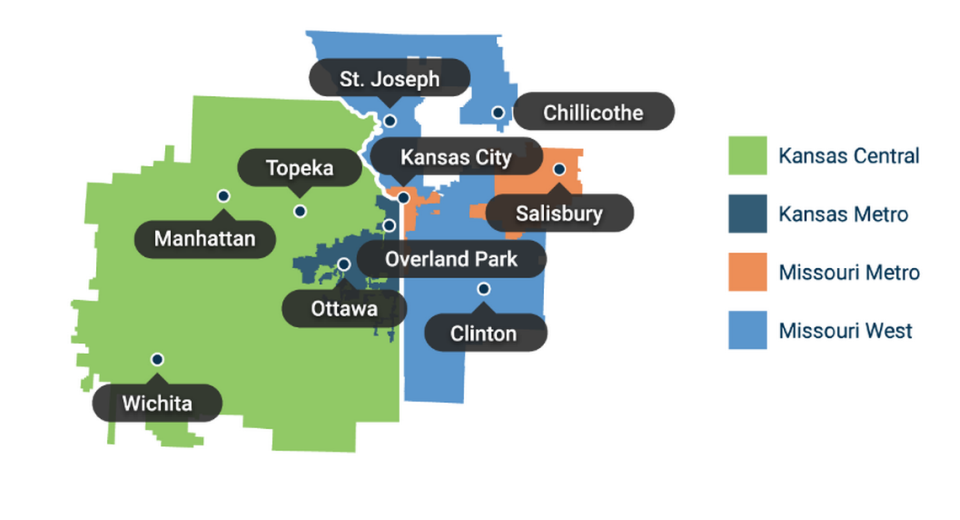

Wichita and De Soto – along with the Shawnee Mission, Olathe and Blue Valley districts – have intervened in the rate case before the KCC, the regulatory agency that will decide whether to allow Evergy to raise electric rates. The company has requested a 25% increase in the revenue it collects from educational customers in its Kansas central region and a roughly 2% net increase among all customers in its Kansas metro region.

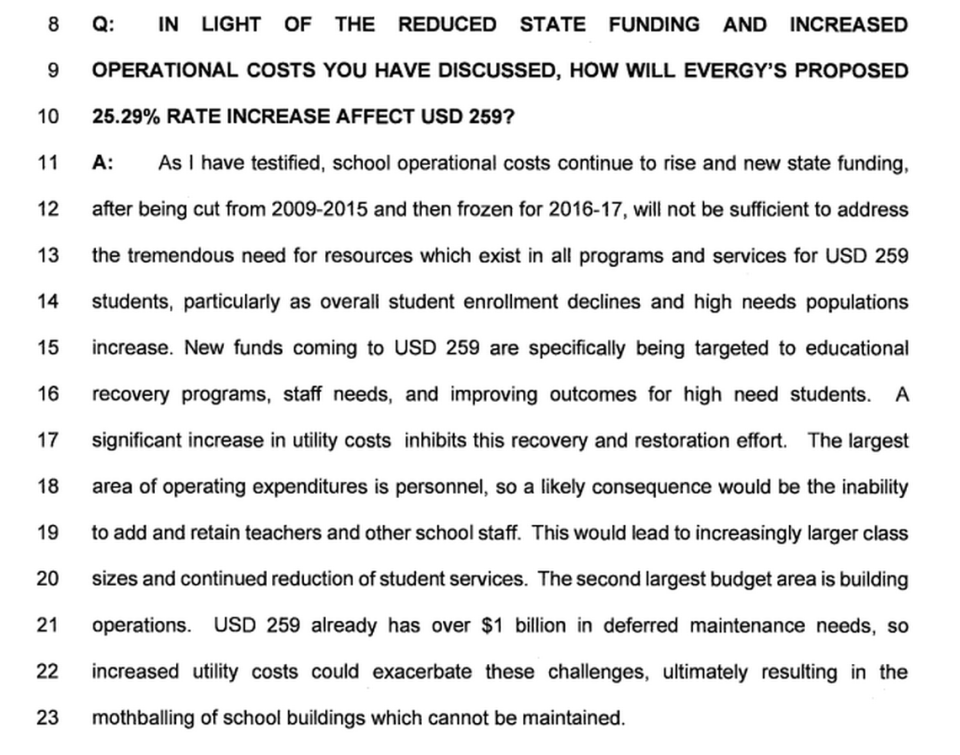

“The largest area of operating expenditures is personnel, so a likely consequence would be the inability to add and retain teachers and other school staff,” Wichita Public Schools Chief Financial Officer Susan Willis said in written testimony last month.

“This would lead to increasingly larger class sizes and continued reduction of student services.”

More than 45,000 students are enrolled in Wichita schools, and the district spends about $8.5 million on electricity from Evergy a year. The district also has more than $1 billion in deferred maintenance costs, Willis noted. Higher electric costs “could exacerbate these challenges, ultimately resulting in the mothballing of school buildings which cannot be maintained,” she said.

Only Wichita has offered formal testimony outlining the feared fallout from an increase, but other districts are also voicing concerns.

De Soto has far fewer students by comparison, with an enrollment topping out at about 7,400. But the district is on a trajectory to grow in the coming years as the construction of the sprawling Panasonic battery plant is expected to draw thousands of workers – along with their families and children – to the area.

The district estimates Evergy’s proposed rate hike would cost it an additional $182,000 a year – money it could use to hire personnel. Alvie Cater, assistant superintendent for administrative and educational services, said the district isn’t opposed to any increase but is concerned by the size of the utility’s request.

“We became concerned from the standpoint of being able to mitigate some of those expenses,” Cater said. “We also recognize that goods and services cost more now and have over the last few years. But we don’t have a lot of options when it comes to energy.”

Blue Valley USD 229 estimates an additional $120,000 in costs each year under the proposed rate increase, according to district spokesperson Kaci Brutto. Blue Valley, with about 22,600 students, currently spends about $8 million a year on energy.

Olathe Public Schools USD 233, with an enrollment of more than 28,000, spent about $5.8 million on electricity last school year. A statement provided by district spokesperson Erin Schulte noted that Olathe and other Johnson County districts are some of the largest energy consumers in the county given their status as several of the area’s biggest employers.

“The rate increase requested by Evergy uniquely impacts our school districts, as electric energy is a large expense in our annual budget,” the district statement said.

Under Evergy’s proposed change in rate, Olathe Public Schools estimates its energy costs “would increase by a substantial amount annually” assuming usage remains constant.

First big increase in five years

The school districts’ concerns are only adding to the growing headwinds Evergy faces as the company seeks its first major Kansas rate hike since it was formed by the merger of KCP&L and Westar in 2018. The company argues it needs the rate increases to recover costs made to modernize the electric grid and ensure reliable service.

KCC’s staff have urged the three-member commission to reject Evergy’s request and instead approve only a smaller revenue increase in the Kansas Central region, which includes Topeka, Wichita and parts of Johnson County. At the same time, KCC staff said Evergy should decrease its revenue in the Kansas Metro region, which includes parts of Johnson and Wyandotte counties.

Evergy also wants permission to seek a second rate increase in part to help pay for upgrades necessary to provide power to the new Panasonic plant. KCC staff have recommended against it, saying there’s too much uncertainty surrounding the project.

The commission will issue a final decision on Evergy’s rate proposal by late December.

For school districts, the prospect of higher electric bills represents an unwelcome headache as they continue to climb out of the turbulent pandemic era and remain on the hunt for more teachers. The potential hike comes after school officials spent the past decade securing more state funding for K-12 education from the Legislature — aid that is now supposed to grow roughly in line with inflation.

Mary Sinclair, president of the Shawnee Mission Board of Education, said “absolutely” every additional dollar spent on utilities is a dollar that can’t be spent on teachers. The district in June estimated it will spend about $7.8 million on electricity during the current school year.

“Any kind of increase … related to Evergy puts pressure on our operating budget,” Sinclair said, noting the district’s budget for the school year is already in place. She added that costs like these highlight the importance of districts maintaining some cash reserves to deal with unexpected expenses.

School districts statewide collectively spend tens of millions on electricity every year. In Evergy’s Kansas Central region alone, the company receives about $32 million in annual revenue from schools, according to testimony from KCC staff (a similar figure doesn’t appear available for Evergy Metro).

“Evergy is conscious of the impact of rate increases for all types of customers,” Evergy spokesperson Gina Penzig said in a statement.

“In Kansas our rates have remained flat since 2017 and our request is well below the rate of inflation since our last rate review,” Penzig said. “Since the merger to form Evergy in 2018, we have reduced operational costs $1 billion across our full company. These savings helped reduce the rate requests this year in Kansas by more than 37%.”

Should schools go greener?

As districts brace for higher bills, the rate request has underscored the urgency surrounding efforts to make school buildings more energy efficient. Districts often have facilities of all ages, ranging from Depression-era red brick high schools and middle schools to sleek ultra-modern elementary schools – all at different levels of efficiency.

K-12 schools nationwide received a D+ grade in the American Society of Civil Engineers’ 2021 Report Card for America’s Infrastructure. According to the report, 53% of public school districts reported needing to update or replace multiple building systems, including heating and cooling – HVAC – systems.

In Kansas, only 165 K-12 school buildings have received the Environmental Protection Agency’s Energy Star certification, which means the facility performs well on measures of energy efficiency. Most of those buildings are concentrated in about half a dozen districts, including Olathe, Shawnee Mission and Kansas City, Kansas.

Just 13 Kansas school buildings have received LEED (Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design) certifications, according to a LEED database. LEED is a “green building” rating system that also uses measures of energy efficiency.

When attempting to improve a district’s energy efficiency, officials sometimes encounter hesitancy over the cost of new, better-running equipment and materials – even if it will save the district more money in the long run. Large capital expenses may require the district to either raise cash through property taxes or go to voters for permission for a bond issue.

“People are always going to look at upfront costs over everything and they’re not going to look at the lifecycle costs, which would really drastically reduce that first cost,” said David Carter, director of the K-State Engineering Extension, which houses the Kansas Energy Program that offers small businesses, agricultural producers, government agencies and K-12 schools with energy-related education and technical assistance.

The KCC operates the Facility Conservation Improvement Program, which is designed to allow schools and other organizations to get past the higher initial costs that can be a barrier to improving efficiency. The program connects school districts with energy service companies, which audit buildings and recommend improvements.

Those recommendations can include everything from HVAC upgrades to installing high-efficiency light bulbs. The improvements are financed at least partly by anticipated future energy cost savings, helping lessen the financial strain on districts.

At least 19 Kansas school districts have participated in the program. Wichita Public Schools has also worked with an energy service company, leading to changes at 26 sites in the last several years and about $600,000 in energy savings so far, according to the district.

Upgrades have included switching to LED lights, as well as replacing boilers and chillers. The work totaled about $17 million, but Luke Newman, the district’s director of facilities, said the changes have been paying off.

“Energy savings have been on our radar for a long time. And although the rate case does elevate the concerns and the cost impact that’s going to come with it, it doesn’t really change a whole lot in terms of how we look at energy savings,” Newman said.

“We’re always trying to look at more opportunities.”