Kansas schools are seeing record numbers of special education students, and fewer teachers

Most Kansas students are back in school, and an increasing share of them are likely to need special education services.

Like most other states, Kansas has seen soaring rates in the numbers of students needing special education services. Last year, a record 81,000 students, or about 15.9% of the state's student population, were identified to receive special services under the federal Individuals with Disabilities Education Act.

That's an increase of 4.5% since fall 2019, the last count before COVID, and 14.5% since fall 2015.

Coupled with an overall shortage of teachers and legally inadequate funding, the increase has put a strain on Kansas school systems, which are required to continue providing special education services with all level of fidelity regardless of other challenges.

More Kansas students are needing special services for learning, emotional disabilities

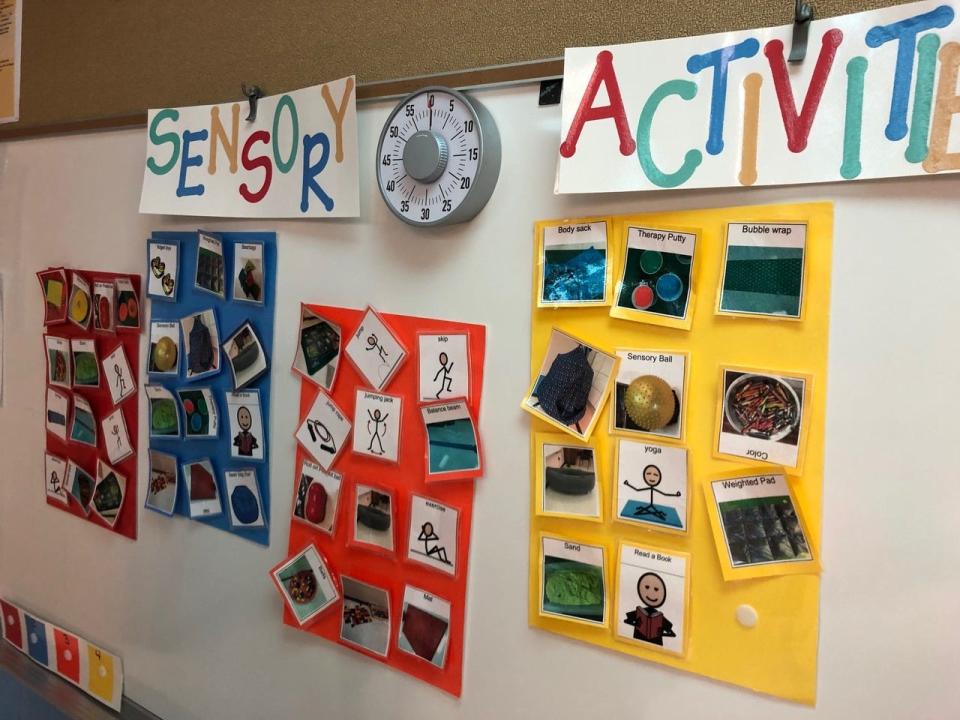

Of the 13 categories for the various special education services a student might need, Kansas — like other states — has particularly seen more students needing services in the learning disability category.

That includes disabilities like dyslexia, and various studies have indicated that anywhere between 20% and 40% of the population have a reading disability.

The growth in number of students receiving learning disability services is believed to be driven by schools being better at identifying such disabilities, especially at earlier ages, as well as an overall statewide effort to better support students who struggle to read.

Parents are also generally more aware of the benefits of special education and are more likely to ask their schools to evaluate their students for a potential need, said Kathy Kersenbrock-Ostmeyer, director of special services for the Northwest Kansas Educational Service Center.

Kersenbrock-Ostmeyer, a longtime special educator, oversees a team that provides special education services to about 1,000 students across 19 school districts — covering an area of more than 12,000 square miles across 12 counties.

“People are not as afraid of the stigma of special education,” she said. “In my early years, people used to be afraid of that, but it’s a lot more mainstream now. Parents do want their kids receiving those special services if that’s what it takes to be successful in school.”

More students are also being diagnosed with autism, as well as emotional disturbances that affect their ability to learn in classrooms.

Comparatively, the numbers of low-incidence students — or students who are deaf, blind, or have significant cognitive impairments — has remained relatively steady, said Bert Moore, director of special education for Kansas State Department of Education.

Kansas schools are short the teachers they need for special education

By federal and state laws, once a student is identified as having a disability and a need for specialized education, schools must provide that education, in spite of any other factors or challenges.

That’s put a crunch on Kansas schools as they battle a shortage of teacher candidates — a problem that has become especially acute in the special education sector.

Kansas’ 377 special education vacancies this past spring accounted for about one in four of the state’s teacher vacancies, according to KSDE data. While the department’s definition of “vacancy” only shows that the position was not filled by someone appropriately qualified for that teaching post, the data still reflects a shortage of people willing and qualified to do the specialized work.

“It’s every state dealing with this,” Moore said. “If it was a salary issue, that could be addressed. But at the same time, it’s an issue every state is dealing with.”

Despite a shortage of teachers, though, schools are required by law to provide their students with special education at the same fidelity. To attempt to maintain that quality, many schools have had to increase special education class sizes and case loads, or look beyond site-based teachers.

Moore said Kansas schools are relying more heavily on itinerant services — a model in which roving teachers move between several schools to assist in evaluating students, training teachers to provide specialized instruction and write IEPs.

“We used that model early on in special education, and then we moved to more school-based services, where teachers are based at those buildings and providing support,” Moore said. “But districts have had to be creative with the number of positions that have gone unfilled. That’s been a problem for us the past three years, ever since we came back from COVID.”

In cases of dire shortages, some schools have had to look elsewhere for help, either to neighboring school systems or private services, which can be costly.

Kersenbrock-Ostmeyer, the northwest Kansas special education director, worries about her ability to find staff to provide services to the 1,000 children who need special education in her area, especially as more teachers consider retirement.

“In one of our districts, we don’t have a teacher, and we can’t find a substitute to cover that school,” she said. “I had to ask a teacher from a neighboring district to go over and help cover those services and oversee special education in that building. It’s a constant issue.”

Full Kansas Legislature support for special education in question

By state law, the Kansas Legislature is supposed to cover at least 92% of any excess costs a school district sees in providing special education services. That’s apart from a legal obligation on the federal government to also provide for 40% of excess special costs.

But the Kansas Legislature’s funding has fallen well-short of that target in recent years. For this year, the shortfall is expected to be about $175 million, leaving funding at a total of about 69% of the excess costs. The federal government is also failing to meet its legal funding target, with its funding estimated to only meet about 13% of its national obligation.

While public education advocacy groups lobbied the Kansas Legislature to fully fund special education to the minimum required by law, lawmakers punted on the issue this spring to instead create the Special Education and Related Services Funding Task Force.

That group, set to meet sometime this fall, will instead study and make recommendations for a potential change in the school funding formula when the Legislature reconvenes this spring. Gov. Laura Kelly has also renewed her call on the Legislature to fully fund special education.

Separately, the Kansas State Board of Education has renewed its call on the Legislature to at least gradually step up to reaching 92% of excess special education costs over the next four years.

On a board that has skewed more conservative and held more narrow votes on even noncontroversial items like federal support for Kansas school programs, that vote recommending increased state special education spending was unanimous among the board’s Republicans and Democrats.

Still, state school board member and legislative liaison Ann Mah, D-Topeka, said she worries that this fall’s special education funding task force — of which the board appointed one of 11 members — will make a recommendation that falls way short of Kansas schools’ need.

“I’m really concerned about what the Legislature might do when try to figure out a new special education funding formula,” she said. “They’re figuring they do a $5,000 average per kid for general education, so they could do something similar for special education. But there is no average special education student.”

More: Kansas lawmakers approve a school budget. What will happen with school choice expansion?

To be sure, shortfalls in state special education funding don’t necessarily mean a shortfall in special education services, since the law is clear on schools’ requirement to maintain that support with fidelity.

But the effects of that shortfall are keenly seen elsewhere in school systems when local school boards must shift general education funds to cover special education costs, which can run into the tens or hundreds of thousands of dollars when even just one student requires intense and deeply specialized services.

State-level catastrophic aid, as well as some federal funding, can help local schools with some of the those significant costs, but schools are mostly left on the hook.

“What that means is that staff in those systems had to make the difference,” said Moore, the KSDE director. “There can’t be any violation of (federal law). You have to serve those students on the IEPs, and you have to find alternative means to provide that service. That can come at a high cost, especially if those services are contracted out to a neighboring or private system.”

Money that might have otherwise gone to hiring additional teachers or buying a new curriculum is instead repurposed for special education students, but that doesn’t mean special education students aren’t seeing the effects of reduced funding.

“You have to remember, special education students are general education students first,” Moore said.

Despite shortage in teachers and funding, Kansas special education is bright

In the meantime, Moore expects the levels of special education students to plateau in Kansas, even after years of dramatic increases.

That’s in large part because Kansas schools are becoming better at identifying the learning disabilities students have, and addressing them generally without the need for specialized and individualized instruction.

Kansas general education teachers, for the most part, are receiving better training on working with students who might have a learning disability like dyslexia, reducing the need for individualized education programs.

Schools are also becoming better at increasing collaboration between special and general education teams, which often results in a better learning environment for all students, said Kersenbrock-Ostmeyer, the NKESC special services director.

“We know that special instruction is important, but that students learn best when they’re with highly-qualified general education teachers as much as possible,” she said. “But again, that’s where that individualization comes in. And one-size doesn’t fit all, so you really have to just structure it for the individual needs of that student.”

As far as teacher shortages, state administrators are confident that some new alternative approaches are key to getting more qualified educators into special education positions.

More: Kansas high school graduation rates increase. Here's why commissioner says it's not enough

Traditionally, Kansas has required teachers to have a special education masters degree to receive a license in that field, but a new program is experimenting with allowing prospective paraprofessionals with at least a year of experience in special education to receive a full teaching license after completing a limited apprenticeship.

The state education department has also seen high numbers of teachers who receive a provisional license to teach special education while they complete the necessary coursework to become fully endorsed for special education.

All that, combined with what an increase in special education funding that advocates hope for this spring, paints a brighter future for Kansas special education, Moore said. Kansas is second in the country for graduation rates for students with disabilities, and it is one of only seven states in the country to consistently meet requirements State Performance Plans and Annual Performance Reports over the past five years.

"Kansas special educators are delivering outcomes for special education students," Moore said.

Rafael Garcia is an education reporter for the Topeka Capital-Journal. He can be reached at rgarcia@cjonline.com or by phone at 785-289-5325. Follow him on Twitter at @byRafaelGarcia.

This article originally appeared on Topeka Capital-Journal: Kansas special education headcounts rising while funding remains low