Karnig Thomasian lived a full life, even as his World War II POW scars remained | Kelly

America said goodbye to another World War II veteran.

But this was different.

Karnig Thomasian’s suffering never ended when the Nazis and the Japanese warlords surrendered in 1945. His wounds from that conflict festered for years.

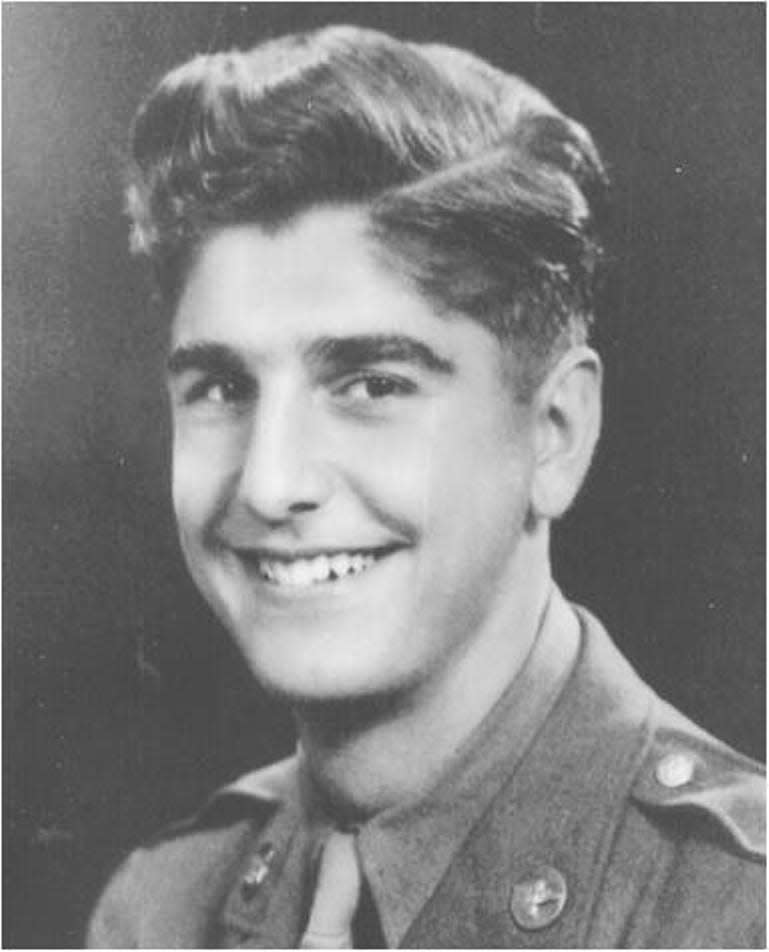

Thomasian, who died the day after America’s annual Independence Day holiday and just nine months short of his 100th birthday, had been a prisoner of war in a brutal Japanese camp in Burma during the final days of World War II.

Thomasian was eventually rescued from the camp. But the war — and that camp — never left him.

Story continues after gallery

Most lives are inevitably framed by memories. Some memories are built by years of positive nurturing — with successful careers, enriching marriages, enduring friendships. Some of the most burdensome memories, however, are horrific scars, inflicted in much shorter experiences and difficult to heal.

Such was Thomasian’s plight.

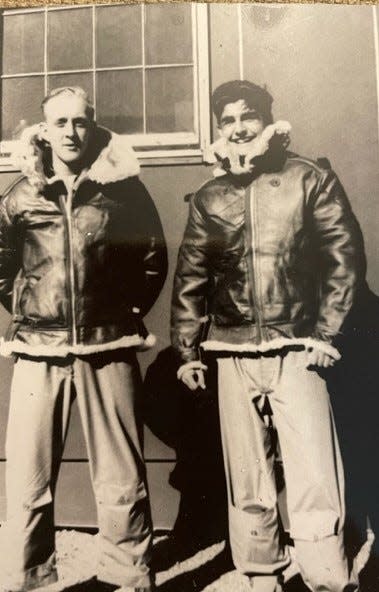

Thomasian, a successful "Mad Men"-era advertising graphics designer who lived many years in River Edge, New Jersey, with his wife and two daughters, was held captive by Japanese forces in Rangoon, Burma, for just five months, from December 1944 until May 1945, after his B-29 bomber caught fire and crashed.

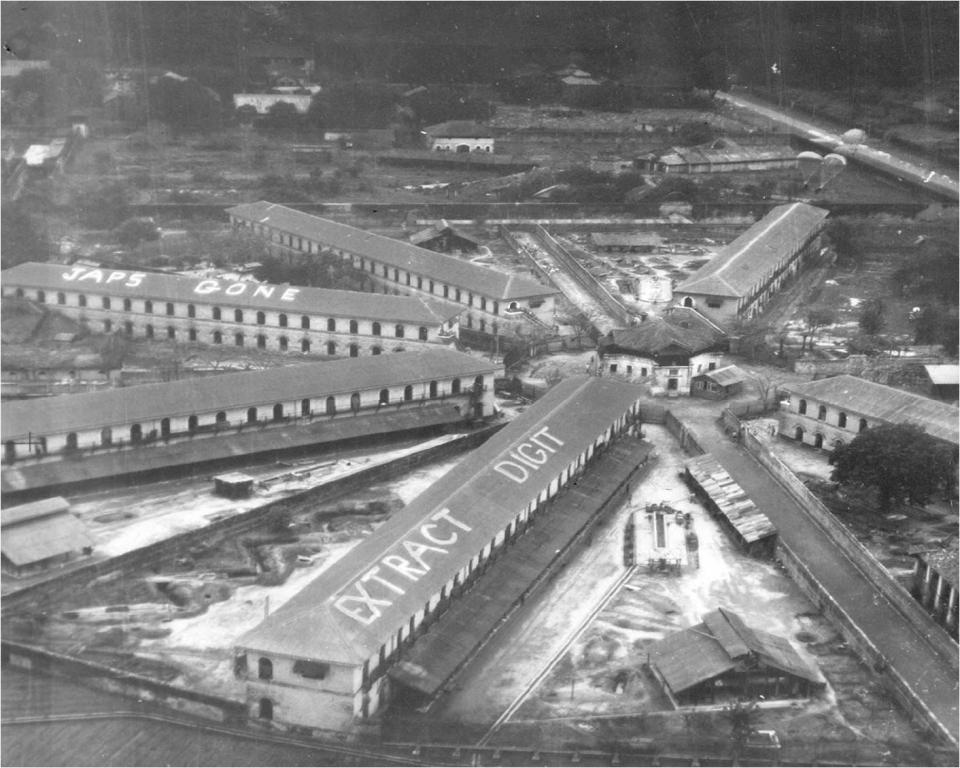

It was only Thomasian’s third mission as a B-29 crew member. Parachuting from the plane after the B-29’s bombs accidentally exploded — Thomasian's first parachute jump — he landed in a Burmese rice paddy. He was quickly apprehended and taken to the Central Jail in Rangoon, which was already home to soldiers from Britain, Australia, New Zealand and China.

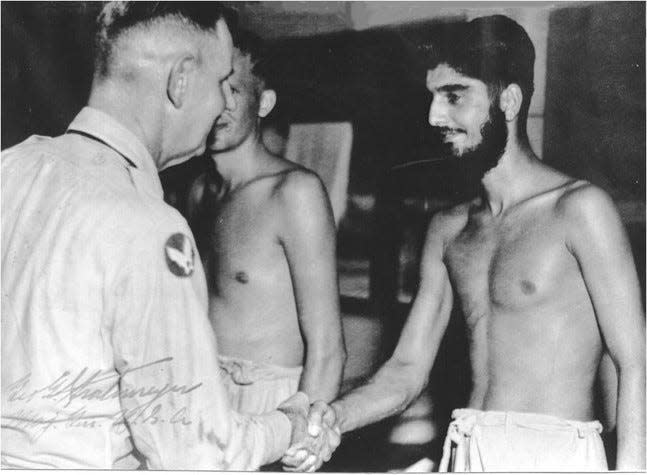

Some prisoners there had already endured more than two years of captivity. Thomasian was lucky. Rangoon was liberated by British forces in May 1945 — three months before Japan surrendered. He was back in his parents’ home in New York City soon after.

But Thomasian’s comparatively short period of captivity — framed by near-daily beatings, mock executions, humiliations and a diet that consisted mostly of rancid rice — handcuffed him psychologically for years afterward with latent anger, guilt and a torrent of other untenable emotions that surfaced in the most unlikely moments.

And so, on Friday, as nearly 100 of Thomasian’s family and friends gathered for a memorial service at his final home for the last decade — an assisted living center in Pompton Plains, New Jersey — many returned to his time in Burma.

“He would always say, ‘I survived prison camp. I can survive anything,’” his youngest daughter, Karla Robertson, 65, recalled in an interview. “But the human brain is not meant to sustain what he saw and experienced.”

Robertson, who lives in Howell, New Jersey, and now counsels corporate executives on how to navigate their own emotional traumas amid the push and pull of pressurized jobs, said her father struggled for years with outbursts of anger, not knowing why his feelings would burst forth or how to control them.

Finally, Robertson said, Thomasian, at the insistence of his wife and daughters, sought help from a psychologist at the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs.

This is where I met him.

Kelly: 'The fear never goes away': Why does NJ tolerate constant worry about oil trains?

It was 1998. I wanted to write about a group therapy session for former prisoners of war who met at the Veterans Affairs medical center in Lyons, New Jersey. All the participants were in their late 70s. All had been prisoners during World War II.

All were still struggling.

Thomasian spoke of how the now-famous “Russian Roulette” scene, portrayed by actor Christopher Walken in the 1978 film “The Deer Hunter,” forced him to confront his own memory of an especially cruel Japanese guard at his prisoner-of-war camp.

One day, the guard placed his rifle to Thomasian’s head. Thomasian closed his eyes, thinking he was about to be killed. The guard pulled the trigger. But the rifle’s chamber was empty.

Thomasian heard a “click” of the trigger and fainted.

Thomasian’s other daughter, Linda Glagola, 68, retired from a human resources position in a Hackensack, New Jersey, corporation and now living on Maryland’s Eastern Shore, remembers the moment when her father, after viewing “The Deer Hunter,” gripped the steering wheel of his car and muttered: “I was just a kid. I could have died.”

Glagola also recalled her father’s unsettled memories of saving himself from his burning B-29 but being unable to help five other crew members who died.

“Daddy carried that guilt for many, many years,” Glagola said.

In another episode at the prison camp, another Japanese guard, brandishing a samurai sword, forced a group of American captives, including Thomasian, to kneel and bend their heads as if he were about to behead one or more of them.

The guard walked among Americans, waving the sword overhead, then walked away, laughing. Thomasian remembers collapsing in the dirt.

Speaking about his experiences with other POWs at the Veterans Affairs medical center allowed Thomasian to open up about his doubts and shame.

He found that other POWs felt the same way.

And, so, the healing began.

When I spoke to Thomasian in 1998, he said he was able to come to terms with his POW experiences after a nearly 40-year career on Madison Avenue.

“Only when I retired," he told me then, "did things start coming back. Even employees who worked for me never knew about my past as a POW."

At Friday’s memorial service, many relatives and friends remembered the personality that Thomasian nurtured on his own as a result of healing his POW wounds. They recalled his deep sorrow when his wife of more than half a century, Diana, died. But they remembered his surprising joy when he met his second wife, Inga, in the garden of his assisted living center.

At the front of the chapel at the assisted living center, a charcoal portrait of Thomasian, drawn by himself years earlier, sat on a maple table with a bouquet of white hydrangeas.

“This is not a funeral. This is a celebration of life,” said the Rev. Tosha Brown, a hospice chaplain who advised Thomasian’s family after his death.

Thomasian’s only grandchild, Alicia, 26, who was born in Guatemala and adopted by Linda Glagola, smiled as she thought of her grandfather's laugh.

“My best memory was his laugh,” Alicia said in a brief interview before delivering an emotional eulogy. “You could hear it in the next room.”

In her eulogy, Alicia spoke of how Thomasian continually bolstered her spirits. At one point, she had to pause for several minutes as she wiped away tears.

“This is the family I came home to as a baby,” Alicia said after regaining her composure. “I am proud to be called a Thomasian. Pops, you were my true grandparent because you believed in me.”

The hourlong service included the reading by Karla Robertson of “The Dash,” a poem written in 1996 by Linda Ellis, which is meant to draw attention to the “dash” between the dates of birth and death on a tombstone. Robertson said her father kept a small magnet on his refrigerator with the poem’s key line: “What mattered most of all was the dash between those years.”

The service also featured a rendition of the Beatles song “In My Life,” a ceremonial playing of taps, a presentation of memorial flags to Robertson and Glagola by two U.S. Air Force service members, and the singing of the “Air Force Hymn” with its iconic line: “Off we go into the wild blue yonder.”

Karla Robertson, in her own eulogy, repeated her father’s final words: “You are my heart.”

As the ceremony ended, Brown offered a final message. She said she never was able to speak to Thomasian. As the hospice chaplain, summoned when Thomasian’s condition worsened, she arrived at his side just after he died.

But she felt she knew him anyway.

“Although I was not able to meet him in person,” Brown said, “I was able to meet him in spirit.”

Mike Kelly is an award-winning columnist for NorthJersey.com, part of the USA TODAY Network, as well as the author of three critically acclaimed non-fiction books and a podcast and documentary film producer. To get unlimited access to his insightful thoughts on how we live life in the Northeast, please subscribe or activate your digital account today.

Email: kellym@northjersey.com

This article originally appeared on NorthJersey.com: World War II vet lived full life, but time as a POW never left him