KC man was accused of dismembering his client. Then he became Tylenol murder suspect

The victim’s decomposing corpse was discovered in the attic of his Campbell Street home.

His legs, severed at the thighs, were shoved into a plastic bag.

Police found the bloody rope used to hoist and likely bind the body. They found a fingerprint.

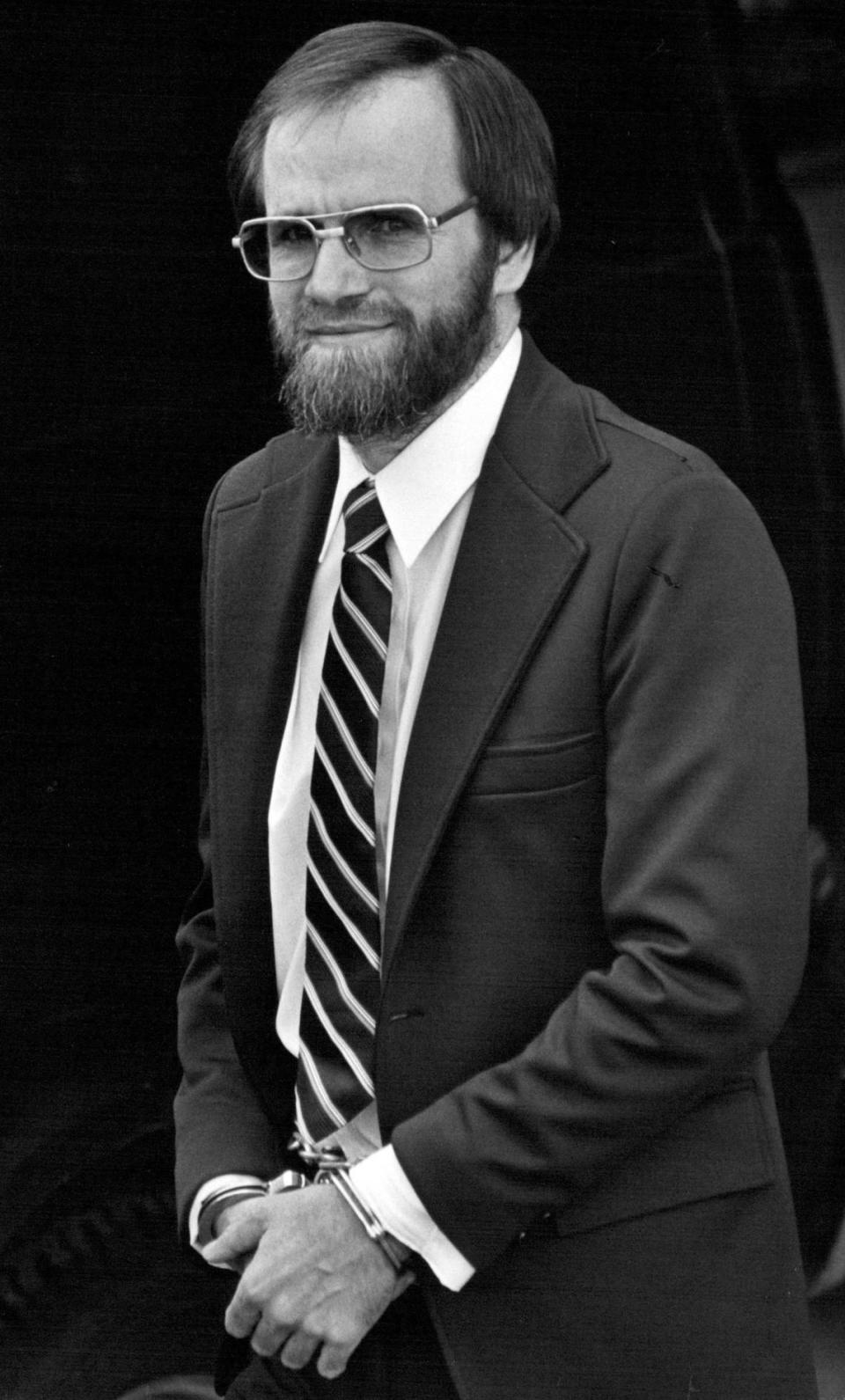

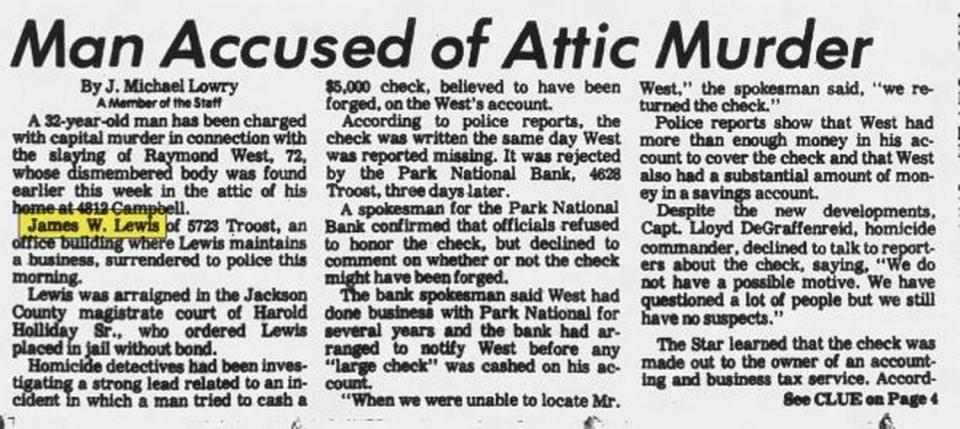

In August 1978, Kansas City prosecutors charged, but, because of shoddy police work, never convicted and were forced to release the man they were sure did it, a seemingly mild 32-year-old Kansas City tax accountant, James W. Lewis.

Lewis, who died Sunday in Cambridge, Massachusetts, at age 76, was long-considered the prime suspect in an even more notorious crime — the 1982 deaths of seven people around Chicago, including a 12-year-old girl, who were killed when they ingested Extra-Strength Tylenol capsules laced with cyanide.

Fear of more poisonings gripped the nation that autumn as Johnson & Johnson recalled 32 million bottles of its product from store shelves, and consumers tossed away their pain relievers. The crime changed the marketplace, ushering in new tamper-proof packaging and new laws.

Lewis, although never charged with the killings, was sentenced to 10 years in federal prison, released in 1995, for attempting to extort Johnson & Johnson and its parent company, McNeil Consumer Healthcare, for $1 million “to stop the killings.” He consistently denied involvement in the deaths.

But it was in Kansas City where Lewis — raised in Carl Junction, Missouri, and who attended the University of Missouri-Kansas City — first became tied to murder in the apparent pursuit of money.

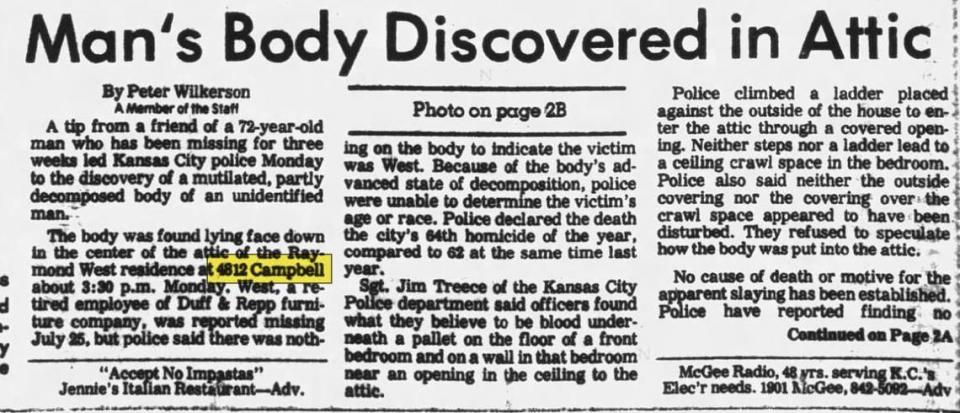

On Tuesday morning, Aug. 15, 1978, a headline appeared at the bottom of the front page of The Kansas City Times, The Star’s then sister paper: “Man’s Body Discovered in Attic.”

Lewis’ name is not mentioned. The story tells of a mutilated and decomposed body found that Monday in the attic of a home belonging to 72-year-old Raymond West at 4812 Campbell St. The body was so decomposed, it was not immediately identifiable. But West, a retired truck driver for the Duff & Repp furniture company, had been reported missing three weeks earlier.

By Friday morning, Lewis was in custody, surrendering to police at his home, 5723 Troost Ave.

Details gradually emerged. West was Lewis’ client. Lewis and his wife, LeAnn Miller, had a daughter, Toni, with Down syndrome. West lived alone in his one-story home near Brush Creek, and absorbed himself in his hobby of genealogy. But he also befriended Toni, who would wave to him from her window. Even after Toni died in 1974, at age 5, Lewis continued to work on West’s tax returns.

Then on July 25, 1978, West disappeared. After his remains were identified, evidence in his presumed murder built. Presumed, because the body was so decomposed, the coroner could not determine the exact cause of death. But on the day West went missing, a check for $5,000, believed to be a forgery, had been written to Lewis, which Lewis claimed was a loan.

Police found rope in Lewis’ car that matched rope used to bind the body. The rope was tied in knots like those on the corpse. They found a note at West’s house saying West had gone on a trip. An expert was ready to testify that it was a forgery and the handwriting matched Lewis’.

The case was circumstantial, but seemed strong. Lewis, who had spent two years in a state mental hospital, diagnosed with catatonic schizophrenia, was facing death in Missouri’s gas chamber.

Then, in October 1979, the case fell apart.

The trial was set to begin that week. But in pretrial hearings, Lewis’ attorneys, Albert Riederer, who would later become Jackson County prosecutor, and Russell Millen, argued that the bulk of the state’s evidence was inadmissible. Lewis had not been read his Miranda rights. Thus the evidence that had been gathered came from an illegal arrest.

The judge ruled the same. Lewis was released.

“I never doubted that he was involved in it,” Jim Bell, who had been an assistant Jackson County prosecutor in the case, told The Star in 1995. “From the check, the handwriting on the note, the ropes, the knots — it was all pretty incriminating.”

In 2009, three decades after the murder case fell through, Bell in an interview with The Star’s Mike Hendricks said of the case, “It’s the one that got away.”

Lewis would next make major headlines in The Kansas City Times in October 1982: “Investigators seek former KC man in Tylenol case.”

Kansas City police officers flew to Chicago and brought boxes of evidence and other materials “relating to the manufacture and composition of poisons that had been confiscated during an earlier search of Mr. Lewis’ Kansas City home.

“Reportedly among the materials were diaries in which Mr. Lewis portrayed himself as a ‘master criminal.’”

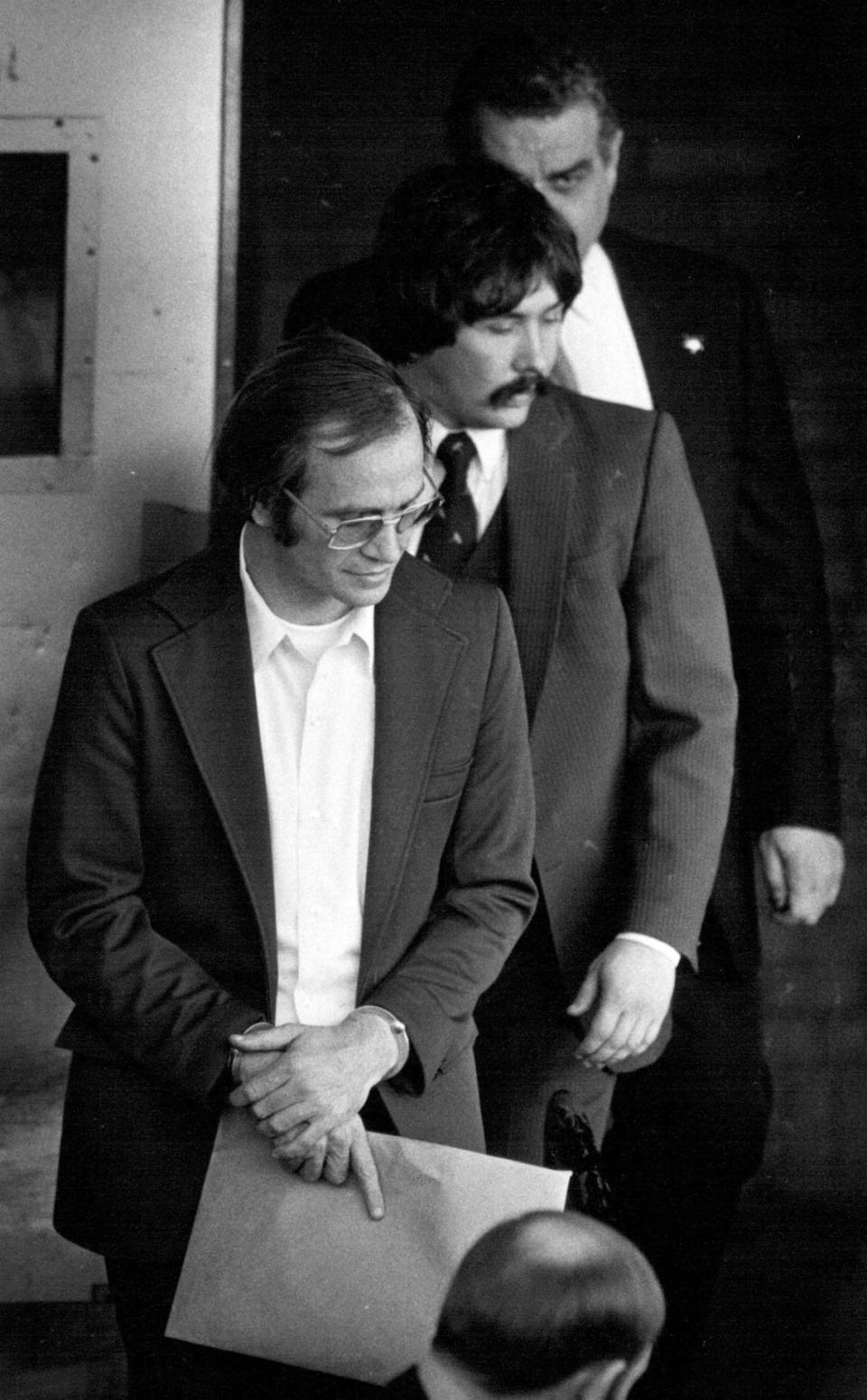

Unable to pay his $5 million bond, Lewis was held in Chicago. In January 1983, he was brought back to Kansas City to face trials on separate charges of both tax fraud and mail fraud. The mail fraud was for a scheme in 1981 to use clients’ personal information to obtain credit cards. He was found guilty that May and given a 10-year sentence. A five-year sentence for tax fraud would run concurrently.

One of his former Kansas City clients, who was then a Boston artist, had donated $11,700 to Lewis’ defense fund.

Trouble again followed Lewis in 2004, nine years after his release. He was indicted in Massachusetts, accused of aggravated rape and drugging a co-worker for sexual intercourse, according to The Boston Globe. He was held without bail for three years. The charges were dropped and he was released in 2007 after the woman refused to testify.

In 2010, Lewis self-published a novel, “Poison! The Doctor’s Dilemma.”

Upon Lewis’ death, a spokeswoman for the Illinois State Police told The New York Times that the Tylenol deaths are still considered an “ongoing” investigation.

Raymond M. West was buried in Carrollton, Missouri, one week after his body was found. He lies in Oak Hill Cemetery.