KC mayor says police funding ballot question misled voters. Could lawsuit overturn result?

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

More than six months after Missouri voters overwhelmingly approved an amendment to the state constitution forcing Kansas City to spend more on police, an ongoing legal challenge seeks to nullify the results.

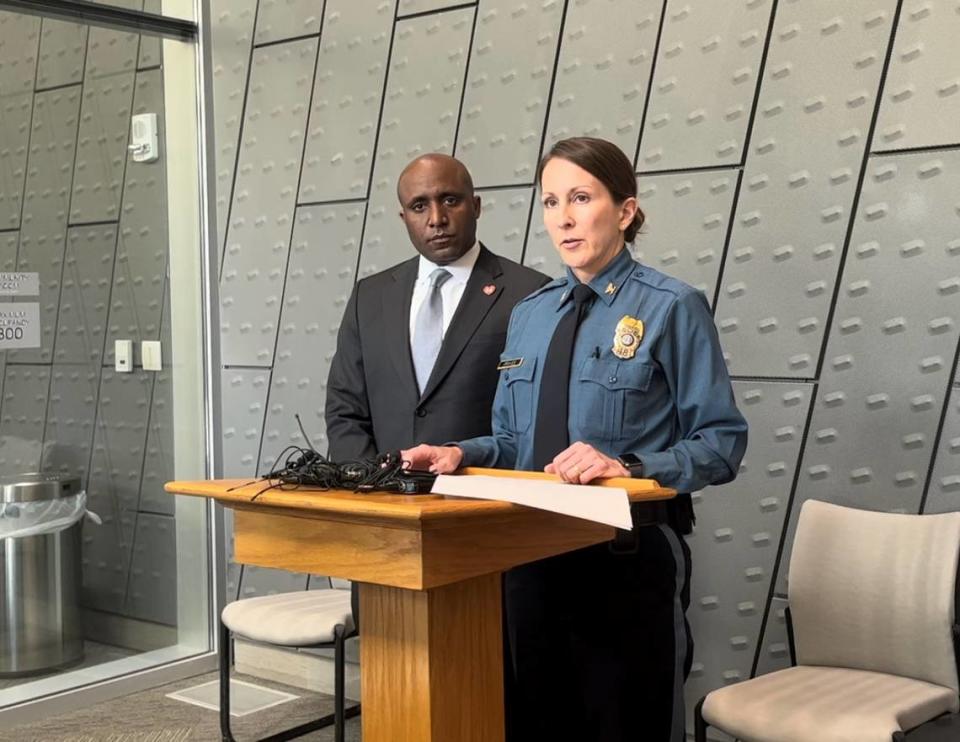

A Cole County judge appointed by the Missouri Supreme Court is set to hear arguments next month over a petition brought by Kansas City Mayor Quinton Lucas alleging that voters were misled in November. Missouri officials, according to the petition, used false financial estimates to get voters to approve the amendment, which mandates that Kansas City raise the allocation from its general revenue fund to the police department from 20% to 25%.

Lucas is asking the state’s high court to set aside the results of the vote, which 63.2% of voters approved in November.

“Mayor Lucas has shown that the fiscal note summary of the constitutional amendment relating to denial of Kansas City taxpayers’ rights to control their own spending was misleading, insufficient, and unfair, and violates state law because the fiscal note summary misrepresented and ignored Kansas City’s local government submission,” Lucas spokesperson Jazzlyn Johnson told The Star.

“The inconsistency of state officials on the Kansas City question and others leads to the unfortunate conclusion that statewide officers are abusing their constitutional duties when it comes to petition initiatives and ballot language based upon their personal political viewpoints rather than the duties they swore oaths to uphold.”

The ongoing case illustrates the tumultuous relationship between Kansas City and Missouri officials over a push by Republicans in Jefferson City to assert more control over how the city funds its police.

Kansas City, which is more diverse and progressive than the rest of the state, is the only city in Missouri that does not control its police force. The department is overseen by a five-member board of police commissioners. Four are appointed by the governor while Lucas fills the remaining spot.

Before the November election, Kansas City officials had informed then-Auditor Nicole Galloway, a Democrat who did not run for re-election last year, and Republican Secretary of State Jay Ashcroft, who is running for governor in 2024, that the ballot measure would cost the city more than $38.7 million and force the city to cut spending on other services.

But, despite repeated requests from the city, the ballot measure that was placed in front of voters — and overwhelmingly approved — stated that “local governmental entities estimate no additional costs or savings related to this proposal.”

Ashcroft and Auditor Scott Fitzpatrick, a Republican who was named as a defendant in the case after succeeding Galloway as auditor, argue in court filings that Lucas is using city resources to contest a policy he personally opposes and lacks legal standing to bring the challenge as a private Missouri voter.

JoDonn Chaney, Ashcroft’s spokesperson, said in an email to The Star that Ashcroft is “confident in the accuracy of the ballot summary.” Fitzpatrick’s office declined comment, citing the ongoing litigation.

State Sen. Tony Luetkemeyer, a Parkville Republican who sponsored the Kansas City police amendment, said that the petition was a “desperate attempt by the mayor to leave open the window for his future plans” to cut funding from Kansas City police.

Luetkemeyer was referring to a failed 2021 attempt by Lucas and the City Council to assert more control over the police budget. The Republican state senator has repeatedly argued that the amendment was a way to push back against a national movement to reduce police spending.

“At this point, Missouri voters in every single county in the state overwhelmingly approved Amendment 4 to support our police,” he said. “I don’t see the mayor getting his wish to overturn the will of voters on his stale legal claims.”

While the amendment passed in every county, Kansas City’s urban core and St. Louis rejected the measure. Separate election offices have jurisdiction over Kansas City’s core and the rest of Jackson County.

Missouri law gives the state auditor discretion in how to write a fiscal note summary. That includes the ability to discount or ignore summaries provided by other government entities, said Chuck Hatfield, a longtime Jefferson City attorney who worked in the Missouri Attorney General’s Office under Democrat Jay Nixon.

The test for the courts, he said, will be whether the fiscal note summary was sufficient and fair. While there have been challenges to fiscal note summaries in the past — and the courts have modified them — no Missouri election has been set aside over a ballot summary or fiscal note, Hatfield said.

“The Supreme Court has said that it’s possible — possible — that they would set aside an election because it was held using an unfair ballot summary,” he said. “The Supreme Court has never actually set aside an election for that reason.”

The case, at its core, accuses Ashcroft and Galloway’s offices of ignoring Kansas City and using false estimates to encourage voters to vote in favor of the amendment. That argument could have far-reaching effects on a separate dispute over a proposed amendment to restore abortion rights in Missouri.

Earlier this month, the ACLU of Missouri sued Ashcroft, Fitzpatrick and Missouri Attorney General Andrew Bailey to force them to finish crafting ballot summaries and fiscal notes for 11 proposed petitions to restore abortion rights. In that case, the ACLU accuses Bailey of trying to coerce Fitzpatrick into adding a fiscal note that says the petitions would cause the state to lose $12.5 billion in Medicaid dollars, a figure which originated with anti-abortion groups that Fitzpatrick has blasted as inaccurate.

Ashcroft has also proposed incendiary ballot summary language for the amendment, according to documents obtained by The Star through a records request. His proposed summary says the amendment would allow “dangerous, unregulated” abortions.

Tony Rothert, director of integrated advocacy for the ACLU of Missouri, said that the ACLU has an opportunity to challenge the fiscal estimates after Ashcroft certifies the ballot title and before the measure is placed in front of voters in an election.

“We anticipate that any dispute about the fiscal note re the reproductive freedom initiative will be resolved long before the election,” he said.

Both cases, which are set for hearings next month, include allegations that statewide officials used, or attempted to use, inaccurate information on ballot measures to entice or dissuade voters.

“The state has an obligation to offer the voters the most unbiased facts about what they’re voting on,” Jason Kander, a Democrat who served as Missouri secretary of state from 2013 to 2017, told The Star. “And when the state doesn’t do that because of political agendas, it does a real disservice to the state and to the voters as they try and make wise decisions in answering the questions on the ballot.”