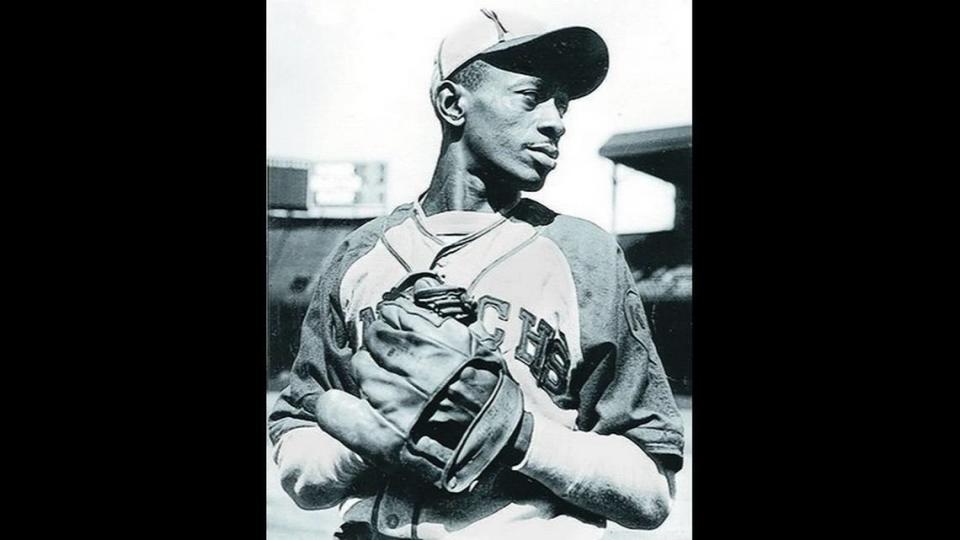

KC tributes to baseball great Satchel Paige are crumbling. Can his house be saved?

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Near the center of Forest Hill Cemetery is a patch of grass called Paige Island. Baseball fans from around the world pay tribute there at the grave of one of the greatest pitchers to have ever climbed the mound.

Leroy Robert “Satchel” Paige played for the Kansas City Monarchs and other Negro Leagues teams for decades before entering the majors late in a long career. He died a legend in 1982.

The Hall of Famer is also a tourist draw seven miles to the north of the cemetery at the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum on 18th Street.

But no one even slows down midway between those two baseball shrines at the sprawling house near 28th Street and Prospect Avenue where Satchel Paige parked his cleats the final 15 years of his playing career and lived out the last 32 years of his life.

There’s no sign out front to say that Paige and his wife Lahoma raised their eight kids there. Or that traveling sports writers would gather on the front porch to hear him tell tall tales and spell out his rules for staying young. A few samples: “avoid fried meats, which angry up the blood,” and “if your stomach disputes you, lie down and pacify it with cool thoughts,” and “keep the juices flowing by jangling around gently as you move.”

At that house, the Paiges would offer their hospitality to royalty of the Black entertainment world in the waning days of Jim Crow. Stars like Duke Ellington, Count Basie and the Harlem Globetrotters could for an evening escape the segregated world and hang loose as the Paiges served them brisket, gumbo or some other fine meal before they left town for the next gig.

But the Paige house, all 3,700 square feet of it, has been empty since the last family member moved out three decades ago and another owner took over. It’s been downhill ever since. Even before a 2018 fire exposed its interior to the elements for two winters, the code violations were piling up.

It got so bad that, back in the 1990s, a judge sentenced the owner at the time to a year and a half in jail for housing code violations at that house and other properties, calling her offenses “a cancer on Kansas City.” The woman, now deceased, ended up serving 90 days home confinement after promising to do better. But she didn’t and the citations continued.

The Santa Fe Place neighborhood association has for years advocated for the house’s revival. A couple of years ago it helped secure a $150,000 grant from the National Trust for Historic Preservation to replace the burned-out roof and keep the weather out.

“It’s been a labor of love,” Santa Fe Area Council president Marquita Taylor said.

But even though the roof has been replaced and the house stabilized, no one has so far come forward with a rescue plan for the rest of the house. But just maybe, someone will now.

Within the next couple of weeks, an agency at City Hall known as the Kansas City Homesteading Authority will start advertising for formal proposals from public and private investors who might have an idea on how to bring the house back to life and have the financial wherewithal to make it happen.

Something wonderful might come of it. Or maybe nothing will. The labor of love was always going to be expensive.

“The house structurally is actually in really good shape,” said Bradley Wolf, the city’s historic preservation officer. “I know it has a lot of fire damage, but it was a very, very solid house.”

City involvement

The city bought the place for practically nothing from the previous owner’s son after the fire with the idea of stabilizing it until someone figures out what to do with it. While they want to see it preserved, city officials aren’t looking to hang onto it long term as a public trust, either.

They will give serious consideration to proposals from applicants who can prove they can pull off whatever reuses for the property they have in mind and are committed to opening the structure to the public in some way.

A Satchel Paige museum would be nice, Wolf said, but house museums generally can’t survive without a deep-pocketed benefactor to cover the losses.

“They really, usually don’t make any money,” he said. “So we’re probably looking at something that would generate money for the property, kind of be compatible with the neighborhood, but also allow for some type of public use and openness to it.”

Whatever the winning proposal might be, the new owners will need cooperation from the Paige family, who own the licensing rights to his name and image, if they hope to market it in any way as the former home of the great Satchel Paige. And what would be the point in buying the place if they didn’t, as there are hundreds of big old empty houses in the inner city in far better shape?

“The property has no value unless you put the name Satchel Paige with it,” said his daughter Linda Shelby, who lives in Lee’s Summit. “I’m sure it would be a tourist attraction.”

Preferably, the family would like to be in control. Shelby envisions the house as an event space for corporate meetings like the Diastole Scholars’ Center on Hospital Hill that would be open for conferences during the week and public tours on weekends.

The Satchel Paige Foundation, of which she is one of two family board members (her sister Pam in Kansas City is the other), set up a GoFundMe page on Friday in hopes of raising $350,000 for the project and getting help from “civic minded individuals and corporations to help us in this endeavor.”

But should someone else be more successful in raising funds for their project, the family wants part ownership as a condition of using her father’s name, Shelby said.

Protect his memory

Demanding a partnership is no money grab, she says. Rather, the six surviving Paige siblings want to make sure that their dad’s name isn’t sullied in the way they think it has been with failed projects not in their control.

Satchel Paige Elementary school closed in 2016, for instance. The youth ballfield that was renamed in his honor three days before his death in 1982 is in terrible shape. The crumbling concrete steps at Satchel Paige Memorial Stadium are only the most obvious signs of the deterioration that city officials say has led to discussions of “possible renovation.”

“Everything that has my dad’s name on it, from the closing of the school, the (baseball) park named after him is falling down. And then finally our home was set on fire,” Shelby said. “Everything associated with my father...is just being dismantled.”

The family’s involvement would ensure, she said, that the rehabbed house would not be an embarrassment years from now, should a new owner fail to uphold their dad’s reputation.

“We are putting the Satchel Paige Foundation contact information in the RFP (request for proposals) so if any proposer wants to partner or use the Satchel Paige name, they will know who to contact,” Wolf said in an email. “We will also be sending the RFP to the foundation.”

Bob Kendrick, president of the Negro Leagues museum, is hopeful that the house can become a civic treasure that honors the memory of the man who Hall of Fame pitcher Dizzy Dean called “the pitcher with the greatest stuff I ever saw.”

“To preserve his home is meaningful,” Kendrick said. “In a perfect world you would love to be able to restore it very much like Henry Aaron’s home in Mobile.”

Paige was born in Alabama, too, though in Montgomery, on July 7, 1906, or thereabouts. His real age was always something of a mystery.

But he spent more than half of his life in Kansas City after the Monarchs signed him in 1939.

Restoring the house where he lived most of those years, playing his harmonica on that wide front porch and looking after the chickens he kept in a coop outside the garage, will be no cinch or it would have been done by now.

Shelby and her siblings know that. After her mom died, she was the one who moved back from Michigan, bought the house from a finance company and lived there until she couldn’t afford it anymore.

“The roof was leaking,” she said. “The gas bills were $600 a month. The light bills were $250, not to mention the water.”

The lender got it back and sold it to the woman who let it sit until someone struck a match. Shelby and her siblings had been mounting an effort to purchase it at the time.

The arson investigation remains open, police say. No one has been arrested.

“Why did it all of a sudden get burned out right when we are trying to do something with it?” Shelby asked. “And the next thing we knew it was on fire. Kendrick called me and told me it was on fire. My girlfriend had already texted me, so I was up.”

She hasn’t been by to see it since, she said. It would hurt too much.