To keep the Colorado River's heart beating, people step in to do what nature once did

PIUTE FARMS WATERFALL, Utah — The muddy San Juan River plunged over a waterfall on its final push toward Lake Powell, trapping endangered fish in the whorl of driftwood, plastic foam and trash that heaved in the eddy below.

This sedimentary hurdle in the river's path didn’t exist before the government dammed the Colorado River downstream at Glen Canyon in 1963, creating Lake Powell. Water backed up past this remote expanse of rippling Navajo Nation desert shore, a point accessible by horse, boat or high-clearance vehicle. Decades of silt piled up below the surface. Then amid drought and overuse, the still water receded and left the San Juan, a tributary of the Colorado, to slice a new course through the mud and create the waterfall.

As temperatures started their seasonal rise in March, native suckers swam up from Lake Powell seeking more natural spawning beds in the river. Instead, they hit an 18-foot wall they couldn't pass without help in the form of orange Home Depot buckets. Once contained, their tails flopped from the rims, and the unexpected assist rendered a telling portrait of the ecological damage control America must employ to squeeze a semblance of nature from one of its most used and abused river systems.

Like most of the Colorado River and its feeder streams — from diverted headwaters to denuded delta — nature here needs a hand from humans if it is to survive what humans have done to it. River flows that already were overallocated for farms and cities have declined by double-digit percentages and temperatures have risen over the last century, drying precipitously since 2000. Climate scientists expect the long-term average flows to continue shrinking in the coming decades.

The states that use the river are haggling over how to spread unavoidable cutbacks, first with new emergency measures expected later this year and then with a long-term and likely more austere shortage-sharing plan for 2027 and beyond. Conservation measures that keep more water stored in Lake Mead have reduced flows downstream through habitats for endangered fish, birds and snakes, necessitating ever more intervention to avoid extinctions.

All around its 246,000-square-mile drainage, the Colorado River is on life support.

At Piute Farms, state, federal and tribal crews take turns each spring camping out and capturing native fish to move around the waterfall and toward cobbly spawning beds in the San Juan. Farther north, on smaller, heavily diverted Colorado River tributaries, hired arborists build artificial beaver dams by weaving juniper limbs through posts driven into the riverbeds, trying to keep some pools wet all summer. On the Lower Colorado, downstream of Hoover Dam, heavy equipment operators bulldoze weedy flats to create new ponds and irrigated lowlands — literally farming habitats for fish and birds that thrived naturally before dam builders arrived in the Southwest.

Throughout the vast watershed from the Rocky Mountains to the sea, state, federal, tribal and nonprofit partners spend tens of millions of dollars a year to preserve a hint of the natural bounty the once-grand river enriched with annual floods that filled backwaters and slaked cottonwood forests.

“The river got tamed and we lost all of those natural processes,” said Tice Supplee, Audubon Arizona’s director of bird conservation. Now it takes heavy equipment and pipes, plantations and hatcheries to give thousands of endemic fish and millions of migratory birds a lifeline. “This is a way to try to bring that back through a managed approach.”

Facing the twin threats of aridification and overconsumption, guardians of the wild now practice a measure of backcountry zookeeping.

Helping nature, one fish at a time

At Piute Farms Waterfall, Talitha McGuire stood atop the bow of a catamaran raft below the falls in March, ready to assist nature. A native fisheries technician for the Utah Department of Natural Resources, she clutched a hoop net on an 8-foot pole, primed to jab at the water when a salmon-size razorback sucker broke the surface. She yipped and howled when she ensnared the fish and hauled it aboard to be dropped in a holding tank.

Native fisheries biologist Brian Hines rowed the boat and minded the generator that powered a steel ball, slitted like a big jingle bell and hanging overboard, pulsing electricity into the water. The current enticed and then momentarily stunned fish in the river. If not immediately within reach, the fish revived and squirmed away, requiring blind stabs of the hoop into the brown water. McGuire left the non-natives — mostly common carp — to swim free, but hoisted a big razorback from the froth.

Later, at camp on the riverbank, they took turns measuring and weighing their live catches of flannelmouth and razorback suckers, waving a detection wand over them to see if they had been previously caught and tagged with a tiny transmitter. Then they clipped a sliver from a fin for later DNA sampling.

“Shh-shh-shh-shh-shh.” McGuire shushed wiggly fish as she hung them from the scale.

The big razorback she had snared weighed in at more than 4 pounds. “Oh, you’re so fat!” she said before lowering it into a tank with a pump that kept it refreshed with muddy river water. At day’s end they would hand-deliver the fish and the others past the waterfall, sending them on their way upstream.

The hike, with arms pulled low by the weight of water-filled buckets, took the two up a steep sedimentary bank around the waterfall, then a half-mile over some sand dunes, through a tunnel of tamarisk bristles and over piles of wild burro dung, then briefly onto some riverside quicksand to dump the suckers back in the San Juan.

“A lot of work for some fishies,” Hines said.

So far, he said, the genetics testing has proved that it works at least on a small scale. One fish that was spawned from a parent caught and transported has shown up back at the waterfall. He had not yet sent the fin clips collected during 2022 to the lab, so there could be more.

Without help, Hines said, these fish will struggle to persist in and around Lake Powell. They spawn in the reservoir and nearby on the Colorado, but those young larval fish don’t survive into adulthood. Besides aiding their migration to more suitable grounds in the San Juan, biologists stock hatchery-raised fish and also patrol the Green River, upstream of Lake Powell. They zap and remove predatory walleye that have invaded the Green after being stocked as sportfish in reservoirs.

Suckers are hardy fish. “If species like that are kind of going into decline,” he said, “there’s something wrong with the system.”

Because concrete dams and diversions supplying and feeding tens of millions of Americans are the ecosystem’s ultimate problem, there may be no end to this painstaking midwifing of the native species and killing of their predators.

“I would like to say there’s an end, but in reality I don’t know that there is,” Hines said. “We’re not going to get rid of the dams — all the dams. We’re not going to get rid of all the nonnative fish. And so there’s going to have to be something done, I think, in the long-term to make (native species) thrive.”

A river with few rights

The river’s own needs have suffered through a century of interstate compacts, settlements and treaties. The so-called Law of the River is not a law for the river. Instead, the suite of river rules developed since 1922 mostly dictates which groups of humans get how much of the water.

The Endangered Species Act and the Grand Canyon Protection Act both contain mandates involving water, but both also face serious limitations when the reservoirs are low. For instance, a Glen Canyon Dam flood release to benefit both Grand Canyon and its rare native fish was put off for years until a strong snow season assured Lake Powell’s storage pool of a partial rebound this year.

The river’s precarious status in its own watershed is why it’s so important for the states to reach a deal that stabilizes their supplies, according to Jennifer Pitt, who directs Audubon’s Colorado River program. Nature only gets its slim share if an interstate deal props up the reservoirs at least enough to keep the river flowing into Mexico. It’s a product of a legal system that doles out water to people and, with rare exceptions, not specifically to the river.

“A crisis for water users makes it much more difficult for (officials) to think about management that includes water for the river, let alone restoration,” Pitt said. If water stores sink low enough, she fears, Congress could override its own mandates, such as a program using some water to create new endangered species habitats along the lower river.

An Arizona State University water policy expert doubts the nation would allow the states to dewater the river within the U.S. now, even though this country and Mexico allowed that to happen in the formerly lush delta south of the border during the last century. The delta was drained before there was an Endangered Species Act, said Sarah Porter, who directs ASU’s Kyl Center for Water Policy. “There are laws in place to protect what’s left,” she said.

The Endangered Species Act may ultimately thwart future efforts to move more water away from riverside farms, such as those around Yuma, and transport it to cities around Phoenix, Porter said. Even artificial nature has its limits.

Lake Powell and Lake Mead, the region’s big storage tanks, dipped to about one-quarter of capacity before rising with the runoff from last winter’s healthy snowpack. They’re expected to climb back to about one-third full, which won’t put them out of risk for catastrophic plunges if dry weather returns, as it usually has over the past two decades.

Pitt hopes the states and the federal dam managers will create a new system that adapts in real-time, hitching water allowances to the current year’s natural flow instead of just tracking reservoir levels.

“We need to acknowledge the uncertainty that we face in the future because of warming temperatures,” she said.

In May, Arizona, California and Nevada released a proposal to share new cuts in water use over the next three years. At 3 million acre-feet in total, it’s less than the U.S. Interior Department had sought from them before an increasingly rare big snowpack piled up in the Rocky Mountains last winter, relieving some of the urgency. If Interior Secretary Deb Haaland approves the deal later this year, it could forestall further interstate squabbling and potential litigation at least until new and potentially more painful long-term river-management guidelines are due for adoption in 2026.

The ultimate goal is to keep Lake Mead from reaching “dead pool,” the elevation so low that Hoover Dam can no longer release water to the lower river that divides Arizona first from Nevada and then from California before it enters Mexico. The river there, approaching its dried-up delta, is a lifeline in the desert, supporting birds that need its food and respite on the long annual journeys to and from nesting areas.

“It does seem like a really perilous time for environmental resources in a place where effectively a lot of species are on life support,” Pitt said.

Life support for a weakened river

Cibola National Wildlife Refuge was built to compensate for the destruction that Hoover Dam wrought on the lower Colorado’s environment. It’s a cultivated bird haven straddling the river on the downstream end of the Palo Verde Irrigation District, one of California’s sprawling farm empires.

In February, excavators at Cibola plowed a gaping ditch across a levee from the river and inserted a new water main. It will serve new backwater ponds that the crews also dug out of the tamarisk-choked flats just downriver, scraping new artificial fish and wildlife habitats from the desert. The goal is to rebuild the kinds of wetlands that the river in its wilder days used to make on its own, delivering water for the trees and bugs that sustain wildlife.

Farther back from the river, a flock of gangly sandhill cranes feasted on corn stubble planted and left specifically for them and migrating waterfowl.

This altered landscape is part of the life support system that Pitt described, a fish and wildlife farm growing the natural resources that a thoroughly domesticated river can’t grow on its own.

“This is big,” Audubon’s Supplee said as she stood on the levee road watching the earth movers. When wet, the new lagoons will expand the haven that already supports about 1,000 cranes each year on their way north to Idaho. On that day, she counted 650. But she remembered decades past, before many of the habitat enhancements, when only a few hundred made the trip.

The cranes are a sight and sound to behold during their late-winter refueling stopover, especially at twilight. After a day of grazing in Cibola’s grain fields, they will lift off to find a place to rest and wet their feet nearer the river. They come first in pairs and small groups, and then in great waves, their croaking cacophony echoing from cottonwoods and desert bluffs until they settle down like gray flamingos in a canal-fed lagoon.

This phenomenon, like so many others among the West’s migrating flocks, now relies on the state and federal funds that effectively farm nature for them, Supplee said. Without that program and the wetlands it creates along this wet ribbon in the desert, birds would struggle to reach their northern nesting zones. Their peril is compounded by the decline of other invaluable waypoints, the inland saline lakes such as the Salton Sea and the Great Salt Lake, she said.

Replicating riverine habitat for water birds and for the bugs that feed neotropical songbirds is essential to continued bird life in the Northwest. “They’ll stop in by the thousands, refuel, then head on north,” Supplee said.

Rebuilding what the Colorado once provided requires constant work. In the old days, the river constantly swelled and shifted to mow down old trees to raise the new. Some birds, like the regionally threatened yellow-billed cuckoo, prefer younger willows and cottonwoods of the sort that spring up after floods. The endangered southwestern willow flycatcher, by contrast, likes the understory among established trees near water.

“They evolved around a dynamic, flooding system that would take the trees out and bring new growth,” Supplee said. A stand of tall willows on Cibola’s edge demonstrates the dilemma. When planted years ago, they were a prime habitat for some species that won’t enter them now because they create an impenetrable wall.

The contractors pushing earth around during Supplee’s February visit were helping America compensate the river for its dams and diversions. They were working for a federal-state partnership that has spent nearly $400 million since 2005 to perpetuate the species that rely on the river and its surroundings. Called the Multi-Species Conservation Program, it is intended to provide 50 years of restoration for imperiled fish and wildlife that are harmed by lower and more controlled flows. It costs about $35 million a year, with the federal government paying half and California, Arizona and Nevada covering the rest.

The U.S. Bureau of Reclamation administers the program from its offices near Hoover Dam. That agency, which also manages the dam, rejected a request by The Arizona Republic to jointly tour some of the habitat that it created and also declined interview requests. When approached after an April news conference about federal funding of Colorado River water conservation, though, Deputy Reclamation Commissioner David Palumbo said the program seeks to make the best of what the river can still provide on its way from dam to diversion canal.

“Given the water shortage we’re seeing,” he said, “we’re looking to see that every drop of water does pass through the habitat in the best way possible. We’re making strategic use of that water.”

The program’s annual report describes a massive undertaking designed not only to scrape more habitat out of the Southwest’s deserts and farmlands, but to capture and safeguard young endangered fish and to rear them until they’re safe from predators and can be slipped back in the river.

In fiscal year 2021, during the winter and spring razorback sucker spawning season on Lake Mohave, biologists with the program captured 38,218 of the young fish in their larval stage. They did this one fish at a time, luring them to light, then netting them. The captives move to a riverside hatchery to be raised in safety until they can be put back or moved to other river segments as they near adulthood.

Lake Mohave, a reservoir downstream of Hoover Dam, holds the species’ greatest store of genetic diversity, according to the report, so ensuring the survival of its young may help razorbacks adapt to fluctuating river conditions.

Another hatchery participating in the program, at Lake Mead, closed last year and transferred its fish to others after the reservoir’s water sank too low for its intake pipe. At least $8.5 million in direct federal funds and $3.1 million from Nevada’s share of federal pandemic recovery dollars is going toward construction of a new intake to reopen that hatchery next year.

Elsewhere along the river, the program supports tree farming for native species that require cottonwoods, willows or honey mesquites, species that were largely crowded out by nonnative tamarisks, after the dams started regulating flows last century.

At the Palo Verde Ecological Reserve, near Blythe, California, the program relies on miles of concrete-lined canals to deliver some of the Palo Verde Irrigation District’s farm water to 1,300 acres of trees. Wildlife surveys last year found yellow-billed cuckoos breeding there and a solitary willow flycatcher, among other rare species.

The Multi-Species Conservation Program intends to create 8,132 acres of new habitat for 27 affected species of state or federal concern, eight of which are federally listed as endangered. That includes 512 acres of marsh and 360 acres of backwaters. By last year, the total acreage created had reached 6,840.

Nonprofits also have added trees to harbor the river’s avian guests, including where the river usually no longer flows at all. Groups including the Tucson-based Sonoran Institute and Mexico’s Pronatura Noroeste have planted bosques of mesquite, palo verde and other natives along portions of the dry riverbed where depth to groundwater is shallowest, an effort that also capitalizes on targeted flows through Mexico’s farm canals.

At the Miguel Aleman restoration site, Pronatura says the partners have rooted more than 100,000 native plants and counted 122 bird species. It’s no match for the massive oasis that birds found on the delta before the U.S. built Hoover Dam and Mexico diverted its share. But without it, they would find only a wasteland.

How toppling tamarisk could help habitats

Yuma’s handsomely forested riverfront is another oasis that took a yeoman’s effort — and an irrigation system — to bring back. Its shade attracts both birds and nature lovers.

“Pshh-pshh-pshh-pshh!” Some of the 11 birders out for a weekly organized stroll around the Yuma East Wetlands mimicked the songbirds they stalked through the palo verdes, mesquites and cottonwoods in March, hoping to draw them in for a closer look through binoculars. An Abert’s towhee bounced through the underbrush.

It’s an underbrush that wouldn’t have been comfortably accessible when Karen Reichhardt moved to Yuma in the mid-1990s, not to her and the other birders, and not to some of the birds. Back then the riverside stretching north from downtown Yuma and the Yuma Crossing National Heritage Area was clogged with nonnative tamarisks, also known as salt cedars, and reeds. These scruffy, poky green invaders have taken over much of the Colorado Basin’s riversides, aided by the unnatural stability left by upstream dams that tamed floods.

Some people did penetrate those thickets and lived along the river outdoors. City residents hesitated to approach, worried about drugs and unsanitary conditions, and called the upstream confluence with the usually dry Gila River “Shit Creek.”

“We thought the river was dead,” Reichhardt said. “There was no hope.”

And yet, when the heritage area and partners with the Fort Yuma Quechan Indian Tribe, the city and the Arizona Game and Fish Department started a program to clear and replant the banks with native species, volunteers abounded. Back then, Reichhardt was a natural resources specialist for the U.S. Bureau of Land Management, another agency that got involved. They battled “tamarisk thickets you couldn’t even crawl through,” she said.

You’d never guess it today, under a tall, leafy canopy where Anna’s hummingbirds zoom and rough-winged swallows dart after insects. Like the marshes a few dozen river miles upstream around Cibola, some of the area is irrigated by canal and culvert from a nearby farm district. Like Reclamation’s multispecies program, the Yuma partners make the most of every drop that passes on its way to its ultimate user downstream. The trees shade walkers and canoeists in a town that blisters in the summer heat.

The birders’ count after an hour that day, submitted to a Cornell University survey app, included 24 species, among them a Bullock’s oriole. They would be back the following week to see what life the renewed forest might embrace.

“It’s just phenomenal,” Reichhart said. “Every single tree you see was planted.”

Across the river and downstream on Quechan land, Tribal Environmental Director Chase Choate checked on workers tending buckets of honey mesquites that would soon be transplanted where they had cleared tamarisk stands. Near the bank, a diesel generator powered a pump moving river water into drip lines to irrigate the latest stand in the 100 acres that the tribe has restored since 2010 on the California side between Yuma and the Mexican border.

They typically add 15-20 acres at a time, and were planning to help volunteers root another 500 or so trees bought for $5 apiece from the Colorado River Indian Tribes’ nursery the following month. Most of the work’s cost is reimbursed through federal grants.

The restored areas, including mesquites and flowering palo verdes, cottonwoods and Gooding’s willows, rise over bare sand, in contrast with the solid tamarisk jungles elsewhere on the river. Ideally, Choate said, when the new forests mature and sink their roots into the water table so they no longer need irrigation, they’ll invite struggling species such as willow flycatchers and Ridgway’s rails, marsh waders formerly known as Yuma clapper rails.

The Quechans seek to restore culturally significant plants, such as arrow weed, used in funeral rites. A handwritten note on the chalkboard in Choate’s office reminded workers of the need to gather some for an upcoming funeral. They’re also planting native berry shrubs, such as wolfberry. “We got our own native superfood here,” he said.

Taming the river to power and water farms and cities brought this local ecosystem to the brink of collapse by favoring nonnative species that thrive in the absence of floods. The tribe can’t undo all the damage, but it is working to maintain a sliver of what its ancestors knew as home.

“The trees and the critters were our ancestors too,” Choate said. “We need to honor them.”

Far upstream, around Moab, Utah, willows are recolonizing the Colorado’s banks without the direct aid of humans.

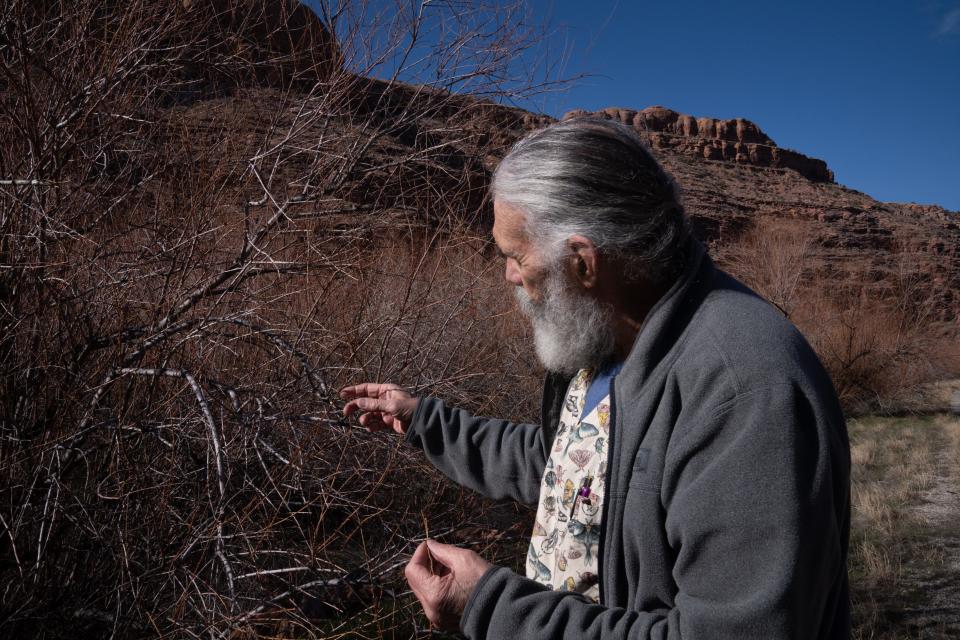

There, in March, Tim Graham dug through the leaf litter under roadside tamarisk bunches and found a tiny beetle ready to emerge for a season of gorging on tamarisk leaves. “Not very big,” acknowledged Graham, a retired federal entomologist who now helps Grand County monitor beetle activity, “but when you get a lot of them they make an impact.”

The impact since 2007, when the government released these insects native to Asia to munch on trees also native to Asia, has been pronounced around Moab. Tamarisks still live there, and sometimes bounce back from one year’s insect assault, inviting beetles back for another round. But throughout this red rock canyon country, Graham said, native willows are regaining some of their old turf.

“It’s been a success,” Graham said. “I don’t think that tamarisk is the dominant thing out here anymore.”

The success can only go so far while dams and canals continue to siphon off the river’s formerly cyclical high flows. The tamarisks themselves altered the river’s floodplain in ways that don’t support cottonwood reestablishment. Acting as strainers, they slowed whatever high water has encroached on them over the last few decades, causing sand to fall out and build the banks higher.

“It has become sort of a semiarid environment, instead of a riparian zone,” Graham said. Restoring the full complement of native trees would require bigger and more frequent floods than this era of drought and diversion generally deliver.

The beetle also is problematic in some parts of the river basin, such as the Grand Canyon and in central Arizona. It hasn’t taken to feasting on native vegetation, but it has spread farther south than scientists thought it could, based on the hours of summer daylight it needs. Where it has defoliated tamarisks that can’t easily be replaced by native trees, it has taken out the only riverside nesting habitat that supported birds including the southwestern willow flycatcher.

The Center for Biological Diversity sued the U.S. Department of Agriculture for releasing the beetles without accounting for their effects to endangered species, and the department agreed to support flycatcher conservation both along the Colorado and in other habitats the beetles threaten, including central Arizona and the San Pedro River.

Environmental concerns 'override everything else'

Human control of the Colorado’s water has created new recreational opportunities, such as bass fishing in Lake Powell or trout fishing in the clear, cold waters below dams on the Green River, the Colorado’s largest tributary. Even these artificial playgrounds exist at the whims of the Southwest’s demands for water and electricity, though, as trout anglers learned anew last year.

Just below Fontenelle Dam, on the Green in southwest Wyoming, Layne Edwards launched his drift boat. He planned to pitch his artificial flies at trout numbering from 200 to 250 per mile. If the dam and the fishing below it were managed to maximize the fishery, he said, that remote, high-desert stretch should hold twice as many fish.

Instead, the fly-fishing guide from Park City, Utah, said the flows fluctuate wildly according to downstream needs, as do the reservoir levels. Water temperatures in summer can reach higher than 70 degrees, stressing the trout. When people hook and wear out already stressed fish, Edwards said, even catch-and-release is a killer.

Edwards fished in spring 2022, before the warm-up. He hoped to return that fall, when introduced kokanee salmon head upstream from Flaming Gorge Reservoir, their eggs drifting and creating a feeding frenzy among both trout and bald eagles.

“It’s kind of a wild fishery,” he said. “Outside of Alaska, you don’t really get to see this salmon process, even though it’s artificial.”

He held out little hope that his goals for the river, both water and fish, would influence dam managers.

“This is where all your water comes from,” he told The Arizona Republic. “Everything that comes out of this dam is a product of what they’ve gotta have in Lake Mead or Lake Powell.” He chose a fly while his fishing partner rowed downstream toward a trout hole. “We’re the last person anyone’s going to listen to for how much water’s going to come out of here.”

By late summer, a trout kill like those that Edwards dreaded on the Green was happening far downstream below the Green’s confluence with the Colorado. The Bureau of Reclamation announced that temperatures at Lees Ferry, driven higher as Lake Powell dropped lower against Glen Canyon Dam, were affecting oxygen levels in the river. Fishing guides in the stretch between the dam and Grand Canyon National Park reported stressed fish, and anglers wading in the river watched trout float past them, belly-up.

Warming waters last year also raised threat levels for native humpback chubs farther downstream in the Grand Canyon. Those fish are fine living in warmer water, as they did much of the year before Glen Canyon Dam started releasing cold water from Lake Powell’s depths more than half a century ago. But the warm band of water atop Lake Powell hosts smallmouth bass, a dangerous predator for chubs. As that surface water plunged closer to the dam’s hydroelectric turbine intakes, the bass started slipping through.

Last year was the first year those predators were confirmed to have bred in the river below the dam. This spring, bass-control teams had captured 26 young bass and spotted two adults between the dam and Lees Ferry, National Park Service biologists reported at a meeting of the dam’s adaptive management program partners in May. They planned to continue removing bass through this summer, including by electric shock that stuns the fish so they can be netted.

As snowmelt started pulsing downstream from the Rockies this spring, river rafters and kayakers were celebrating. Kurt Schroeder, a parks manager from Colorado Springs, Colorado, pumped up a raft for launch at Green River State Park in Utah, ready to join friends on a five-day float that would end just outside Canyonlands National Park.

Schroeder has floated and kayaked the West for 25 years, including twice through Grand Canyon. He believes the region’s thirst for the river’s water threatens a way of life, one that is written in marker on his floppy hat, an entry for each trip.

“We don’t want to lose our ability to raft these rivers and kayak them,” he said. “I can’t say it’s our life, but golly it’s fun.”

A warming climate and continued overuse endanger the natural wonders that make being on the water worthwhile, he said. One big winter’s snowpack won’t reverse that, and he hopes everyone among the millions who draw water from the river will do their part. Green grass, for instance, belongs in parks and not lawns, he said.

“The environmental concerns, as far as I’m concerned, override everything else.”

‘Drawing a line in the sand’

Throughout most of the Colorado and its web of tributaries, the chief environmental problem is far more basic than the unnatural regimentation of dam releases, the takeover of floodplains by invasive shrubs and sand, or even the menace of predatory fish that native species did not evolve defenses against.

It’s the water.

“Society continues to manage our desert rivers as if we think that fish don’t need water,” said Phaedra Budy, a Utah State University professor of fish management and aquatic ecology. She made the assertion in an introduction to research she and colleagues published about how still more new diversions will push native fish toward the edge. “If we continue down this path, we will watch native fish, some of which are found nowhere else on Earth, blink off the planet.”

Budy and Utah State colleague Casey Pennock co-led the 2021 research, published in Fisheries magazine, that studied four tributaries of the Green and found that among them, only the White River, flowing from western Colorado into eastern Utah, had sufficient water with a relatively natural flow schedule to provide safe haven for suckers and chubs.

Only the White has the right balance of water, sediment, sandbars with backwaters, sheltering cottonwood forests and pool-forming deadwood to sustain themselves without hatchery help. They didn’t study the Yampa, farther north, which also has favorable conditions. Those are the only two sizable tributaries that still favor native fish, they say, yet both rivers face calls for more water development.

The White has long been the subject of a dam proposal in Colorado. Protecting its flows could require action by the U.S. Bureau of Land Management to designate a conservation area with federal water rights, Pennock said.

“We’re kind of drawing a line in the sand and saying it’s important and we should conserve it,” he said.

That line was crossed long ago on Utah’s Price River, another relatively small tributary, but one that barely flows past all the farms by late summer and that can’t sustain fish or beavers year-round.

So Utahns are doing the beaver’s work in hopes of bringing the fish back.

In late March, a gang of friends from northern Utah’s Cache Valley waded chest-deep in the Price just downstream of Woodside, a U.S. 6 crossing over the stream north of the town of Green River. They dragged juniper limbs lopped from the slopes closer to Soldier Summit, the mountain pass leading to Utah’s urban front. They had hauled them there because the Price Valley’s scrubby barrens, even at riverside, no longer supply the kind of stout wood they had in mind for clogging up the waterway.

The water had risen sharply since the last time they worked there, but it hadn’t fully immersed the V-shaped “BDA,” short for beaver dam analog, they had built under contract with the state. The structure, woven among posts they had pounded into the riverbed with a motorized driver, spanned the 12-foot-wide river and forced some of the risen water to flow over it, creating a foot-tall cascade. It’s the kind of work that both fish managers and groups including Trout Unlimited are supporting in several Colorado tributaries.

The muddy water obscured the mass below the Price’s surface, so it wasn’t clear whether the limbs the crew had loaded into it on their previous visit still held, or if the posts had instead caught new sticks floating down from elsewhere. Either way, it would do, even though it appeared the high water would keep them from loading as much wood into it as they had hoped.

“That’s the goal right there,” said Wes Newman, a Minden, Utah, arborist. Wood slowing the river, creating ripples and catching sediment to reinforce the obstacle should eventually help create little pools to cool fish.

“That’s satisfying to see, even if we didn’t get to weave it the way we wanted,” said Aaron Lerdahl, of Logan, Utah and, at 23, the youngest of the contracted workers. Their work was altering the waterway.

A competitive weightlifter at his hometown university, he barreled through the Price’s springtime depths, dragging armloads of juniper limbs to stuff between the posts he had already driven into the riverbed. The water lapped at the top of his chest waders and dampened his Hawaiian shirt as he filled the gap between a double-chevron of posts, then compacted the limbs and added more as his colleagues tossed them from the banks.

Slogging upstream again to find the next structure, he turned to look back at his latest creation’s newly formed ripple, and said it again: “Oh, that’s satisfying.”

On inspection for Utah State river researchers later that week, geomorphologist Scott Shahveridan was less satisfied. At every structure he reviewed, he wanted more: more width, more density, more wood.

Wood drifting and lodging in rivers is what adds complexity, and ultimately what aids fish, he said. Even if blown out by the next flood, more wood coming from one structure to the next will help the cause. Until now, the altered river has flowed in a largely unimpeded shot to its confluence with the Green, rarely collecting in deep pools or eddies.

So long as irrigators along the Price effectively drain it during summer, Shahveridan said, native and endangered fish can’t sustain themselves there.

“This thing gets sucked dry,” he said.

A U.S. Geological Survey graph tracking flows past the nearby gauge show that the Price fluctuated wildly according to human needs last summer, from a high in the hundreds of cubic feet per second to a low of 0.27 cubic feet per second on Aug. 14, and back. Such dry-outs would leave any surviving fish gasping in pools, if any such pools existed. The goal with the wood structures is to build barriers and sandbars that can hold water until the next wave of dam releases, Shahveridan said.

“If these are the only places that maintain water,” he said, “then we need these places to exist in the first place.”

Until now, they haven’t. The Price is deeply channelized, in places pulsing below 10-foot-high banks as if through an excavated flume. As with other Colorado Basin streams, Shahveridan said, this one was colonized by tamarisks after irrigators started altering its flows. Their intermingled stalks slowed the occasional floodwaters, filtering out sand and building up the banks until cottonwoods and willows could no longer grow there. It’s a cycle that robbed the river of its wood.

Now the wood is going back in, in the form of BDAs and “PALS,” or post-assisted log structures meant to mimic a tree falling across part of the stream. If they sufficiently slow the flow and cause sediment to drop out in strategic locations, pools will emerge during dry seasons.

How well they succeed in attracting native fish such as the Colorado pikeminnow into the Price and sustaining them there may ultimately depend on collaborations with farmers who own the water rights. The Nature Conservancy is working with Utah and an irrigation district to move some unused canal water into a reservoir for release into the Price when flows get critically low.

“Who cares how topographically complex your streambed is if there’s no water in it?” Shahveridan said.

The river calls

Tending to nature in this highly unnatural environment requires keeping one eye on the long view to recovery, and one on each step along the way. For McGuire, the Utah fish technician netting and transporting suckers upstream, it’s a calling that has anchored her in her home waters on the Colorado Plateau.

McGuire grew up in Flagstaff and went to college in Iowa with the idea of working abroad, but then took on a series of jobs in her home region, each helping her to see that she was needed here. She worked on the program to conserve endangered condors, and also on the electrofishing program in Grand Canyon’s Bright Angel Creek to remove nonnative brown trout so they wouldn’t eat humpback chubs. She guided young people on educational raft trips in Utah. Then she joined the state’s native fish program.

“You don’t have to go very far to have an impact,” she said.

She sees a Colorado River and tributaries that need her help. “I don’t think it will ever go back to the way it was because humans have had such an effect on the environment.”

Still, in an age when so many species are disappearing or at risk of extinction, each razorback sucker she helps on its way seems like a gift from the past to her, and from her to the future.

“You just feel like you’re holding this really, really special thing,” she said. “And you’re like, ‘Yeah buddy. You’re surviving.’”

Brandon Loomis covers environmental and climate issues for The Arizona Republic and azcentral.com. Reach him at brandon.loomis@arizonarepublic.com or follow on Twitter @brandonloomis.

Environmental coverage on azcentral.com and in The Arizona Republic is supported by a grant from the Nina Mason Pulliam Charitable Trust. Follow The Republic environmental reporting team at environment.azcentral.com and @azcenvironment on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY NETWORK: Why keeping the Colorado River healthy is a constant struggle