How Louisville Is Embracing the Legacy of Hunter S. Thompson

Horses are a minor footnote in Hunter S. Thompson’s 1970 article, “The Kentucky Derby is Decadent and Depraved.” The piece is less about what Thompson saw than what he hoped to see––the depravity that exemplified the culture of his hometown; the brouhaha, the drunken Kentucky colonels identifiable by whiskey-stained linen suits, but clean shoes. Instead, he found that depravity in his own reflection. The story was a departure from the journalism he’d been practicing. After it was published, he was convinced he was finished as a reporter. But when it came out, Thompson said in an interview with Playboy in 1974, he got calls and letters saying it was a breakthrough in journalism. “And I thought, ‘Holy shit, if I can write like this and get away with it, why should I keep trying to write like The New York Times?’ It was like falling down an elevator shaft and landing in a pool full of mermaids.”

One of those calls he got was from an editor, who said the writing was totally gonzo. And with that, gonzo journalism was born.

However. Anyone invested in the big hats and juleps and tradition of the Derby—anyone who felt even a smidge of local pride—would have been livid at his depiction (and opinion) of Louisville. Which is part of the reason why, when poet Ron Whitehead organized a tribute to Thompson in Louisville in 1996, Thompson wanted a bodyguard.

That’s also probably why, in the weeks leading up to the event, after the guests’ rooms were booked at the Brown Hotel, flights were scheduled, and Whitehead’s team of student assistants worked through to-dos, the funding for the tribute was pulled. Donors were likely grumbling about the press coverage that no-doubt highlighted Thompson’s history of misdeeds: his drug-addled persona; how he was “run out of town” as a teenager. Someone must have brought up the incident when, while “reporting” the Derby article, Thompson maced the governor's box as well as his collaborator, illustrator Ralph Steadman, whom he had only just met.

After a few phone calls and some hand-wringing, Whitehead decided to go ahead with the event, and ate the bulk of the bill himself.

And so, on December 12th, 1996, Thompson stood in the stark halo of a spotlight, one arm around his childhood friend Gerald Tyrrell’s shoulders, facing a completely packed Louisville Memorial Auditorium. Thompson wore the iconic large-frame glasses, khaki pants, and white sneakers that would soon become part of myriad cheap Halloween costumes. It was the 25th anniversary of Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas. Thompson was 59, and some say he was already long past his prime. Standing next to his childhood friend, Thompson looked nervous, but happy. “All of the trouble I ever got into growing up,” said Tyrrell, “was with Hunter.”

“He did seem happy to get finally a hero’s welcome,” said author Michael L. Jones, who was there that night. “But that was at the end of his life.”

It was, in fact, the last trip Thompson would make to his hometown. The tribute, though, was the beginning of a decades-long road to this “year of gonzo,” which is what Whitehead has dubbed 2019. So far there have been three exhibitions at three separate Louisville institutions celebrating Thompson’s work. There was a day of tribute at Churchill Downs—which is where the Kentucky Derby is run—called “Thurby Goes Gonzo,” attended by Ralph Steadman, who hadn't been back in 49 years. And GonzoFest, the literary and music festival honoring Thompson’s life and work, is in its ninth year.

“The ‘year of gonzo’ is Louisville's love letter to gonzo journalist Hunter S. Thompson,” reads a headline in the Courier Journal from July. Like any love letter, it’s underscored by the tension in its making, and all the messes that lie in its wake. But those set on honoring Thompson’s legacy in Louisville are hopeful—determined—that the love will last; become codified, legally bound, and universally recognized.

But it started with that tribute. The four-hour affair included a reading of Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas by Johnny Depp, who had been living at Owl Farm, Thompson’s home in Colorado, immersing himself in gonzo before adopting the role in Terry Gilliam’s film. The former mayor gave Thompson keys to the city and made Thompson, and Depp, Kentucky Colonels. Historian Douglas Brinkley spoke. Warren Zevon played songs. Throughout the evening, Whitehead emceed and Thompson deployed a fire extinguisher, aimed at whoever was talking. Thompson’s mother, Virginia, was there. So was his “bodyguard,” Bob Braudis, the former sheriff of Pitkin County, Colorado. And somewhere offstage, Thomspon’s son, Juan, was sick with anxiety as he waited to give the last speech of the evening. He would say that he loved and respected his dad (“Well done, man,” Thompson told his son afterwards.)

The night was not without chaos. At some point a fire broke out. Thompson fled the scene. Guests broke furniture. Juan Thompson writes about it in his memoir, Stories I Tell Myself: Growing Up with Hunter S. Thompson: “I heard stories of [Hunter] driving a car down sidewalks in downtown Louisville at high speed, a wall on one side and trees on the other, while Braudis hung on, white-knuckled.”

Thompson may have changed history, but he was a pain in the ass. Now, his caricature is more well-known than his writing. The literary world doesn’t really know what to do with him. Plenty of people think his major contributions dried up in the ‘70s. His hometown, though it’s coming around, has remained neutral, or distractedly disinterested. When Thompson died by suicide in 2005, Michael Lindenberger was working for the Louisville Courier-Journal, the state’s highest-circulation newspaper. They gave Thompson’s death a single column, said Lindenberger. “There was a lack of hometown appreciation.”

When Dr. Rory Feehan, a Hunter S. Thompson scholar based in Limerick, Ireland, visited Louisville for the first time this year, he noticed an absence of permanent public embrace of Thompson. “Why don’t they have a boulevard or street named after him? He’s an icon. This great writer is part of the cultural heritage of Louisville.”

Though GonzoFest draws a good crowd each year, and the general opinion of him seems positive—there’s a banner, and these exhibitions—from the perspective of ardent believers, it’s all come late, and is still too little.

“Growing up here, in the ‘80s, it was other young people who told me about Hunter Thompson,” said Jones. “You hear, ‘Oh that’s where Hunter went to school.’ But there is no official recognition. In a way, it’s not unlike Muhammad Ali, who went from being a draft dodger to having the airport named after him. We can embrace both of them only when they are aren’t dangerous anymore.”

The city of Louisville is under-appreciated. Yes, there’s the Kentucky Derby, and everyone knows about the Louisville Slugger, the whiskey, the horses and all the grass. But there’s a lot more to it than the greatest hits. It’s a confluence of urban and rural, traditional and avant-garde—it’s the old-world yet offbeat middle-of-America. There are restaurants with fashionable tile counters and flights of bourbon served on rough-hewn wooden boards, and massive hotels with tall mirrors and calculated lighting. There is also a charming cultural mix of the polite midwestern and southern hospitality that compels residents to ask, genuinely, how exactly you’re doing, and wait for the answer, and wonder if you’ve been having a nice visit, and if you’ve been to the Muhammad Ali Center or 21c yet.

It’s also got a complicated history, and a relationship to it that is complex. A good example is whether or not the John Breckinridge Castleman monument should be moved, an argument that has been causing some trouble. Castleman was a Confederate officer and the organizer of the American Saddle Horse Association. His monument depicts him riding a horse. Historians consider Castleman progressive, and some go so far as to call him an early champion of social justice. Yet Castleman has become a symbol of everything bad about the confederacy, as Jones said. Jones is on the board of the Louisville Historic League and recently argued that rather than worry about removing the Castleman statue, Louisville should consider using the time and money it would take to “edit history” to make monuments for other important Louisvillians. In particular, women and people of color.

How does a city choose who to memorialize? And who even is an unimpeachable hero? As Jones wrote, “Murals of Muhammad Ali have been vandalized… by people who claim that he was anti-Semitic and homophobic. If the city’s favorite son doesn’t have universal appeal, who does?”

Probably not its other wayward, fire extinguisher-wielding son.

Hunter Stockton Thompson grew up on Ransdell Avenue near Cherokee Triangle, at the edge of the Olmsted-designed park of the same name. High-shouldered trees stand on elevated lawns between compact shade gardens; hedges fraught with porcelain berry line sidewalks and alleys and obscure the diverse, colonnaded––dormer-windowed, Ashlar-stoned, mansard roofed––homes built at the far end of plots. The neighborhood has a quiet, classical mystique. Thompson’s family home, one of the more straightforward stucco bungalows, could fit in neatly on any street in any suburban city from Denver to Sacramento. On the map, it sits in a little wedge between Muhammad Ali’s grave and the Castleman Monument.

Thompson was a middle-class kid with what we would now call “a troubled home life.” His father died unexpectedly, when Thompson was a teenager, and his grieving mother was an alcoholic. Thompson’s bad-boy tendencies went unchecked. He got one important break when a teacher noticed his talent with words. The teacher got Thompson recommended for a fancy literary association, where kids wore suits and talked about literature on the weekend.

One night, Thompson was out being bad with a couple of his rich friends when one of them held up a car and threatened a passenger. It may have been Thompson or it may have been one of his friends; accounts are mixed. But all three were arrested. The other two boys were let off—one had a lawyer father, the other only lost a scholarship to Yale. Only Thompson was jailed, and unable to graduate. Then his literary club decided to expel him, too.

To cut the jail sentence to the minimum, Thompson joined the Air Force and left Louisville for good. But he took the time to throw bottles of beer through every window of one former teacher’s home before he left. Then he did it again once the windows were fixed.

Fans and scholars point to this moment in Thompson’s life as the true seed of gonzo. And though it was the success of his book on the Hell’s Angels that garnered him the assignment, and the authority to write the way he wanted, it wasn’t until 1970, when Thompson returned to Louisville to cover the Kentucky Derby, that the term was coined.

It was editor Bill Cardoso who first called Thompson’s work “gonzo,” and it was after reading the Derby piece. Gonzo is supposedly Cajun slang that made its way into New Orleans’s French Quarter jazz lexicon, meaning “to play unhinged.” At least one scholar has said that gonzo could also be south-Boston Irish slang for the last man standing after a night-long drinking binge. Either way, Thompson liked “gonzo journalism” to describe his work, and the phrase stuck.

Gonzo journalism wasn’t just a writing style, it was a public persona. It was the Thompson interviewed on TV—his antics, his lifestyle. It was the illustrations. It was a performance. It’s the package that biographer William McKeen says makes Thompson the “favorite writer of readers who don’t read. They’re attracted to the caricature.”

The caricature was Thompson’s best and worst creation. It made him famous and crushed the serious writer beneath it. The task of scholars and Gonzoville crusaders is to untangle that mess of myth and man; of hijinks and craft. To show that “gonzo” was the peculiar and very precise voice of Hunter S. Thompson—his eye for injustice, his chip on the shoulder, his years spent retyping books to get the rhythm. His deep sense of the absurd, and his dedicated writer’s sensibility. His self-described “lazy hillbilly” attitude as well as his southern gentleman’s demeanor.

“He is inextricably bound to Louisville,” said McKeen. “No matter what level of fame you achieve, you always want to know you’re well regarded back home.”

Thompson returned to his hometown from time to time to point out its flaws, and, as an armchair analyst might say, win its approval. His investment in and resentment towards Louisville is well illustrated in a piece he wrote in 1963, called A Southern City with Northern Problems. In it, Thompson points a finger at the city boasting progress—desegregation in schools and an ordinance outlawing racism in any “public accommodation”—while its systemic racism was stubborn as ever. African Americans in the city, he wrote, “have improved from ‘separate but equal’ to ‘equal but separate.’”

Being right is harder than is often-enough acknowledged. The compulsion to articulate the feeling that something is off—especially if that something is accepted as normal by a group of people who shaped your worldview—comes at the price of alienation.

“The outsider in the community is the one who is misunderstood and who sees everything clearly,” said Ron Whitehead. “Hunter had that gift, that gift of seeing into things, into situations, into people instantly. Like the great poets do.”

In the mid-1990s, Ron Whitehead and Douglas Brinkley, both professors at the time, had a conversation about why Louisville wasn’t honoring Thompson. Someone needed to do something about it. Because Whitehead lived there, they decided, he would take up the helm. Not long after, Whitehead took his family to visit Thompson. That’s when the idea for the ‘96 tribute began to take shape.

Another Louisvillian named Dennie Humphrey called Whitehead some years after the tribute with the idea of starting a literary and music festival in honor of Thompson. Attendance is now in the thousands.

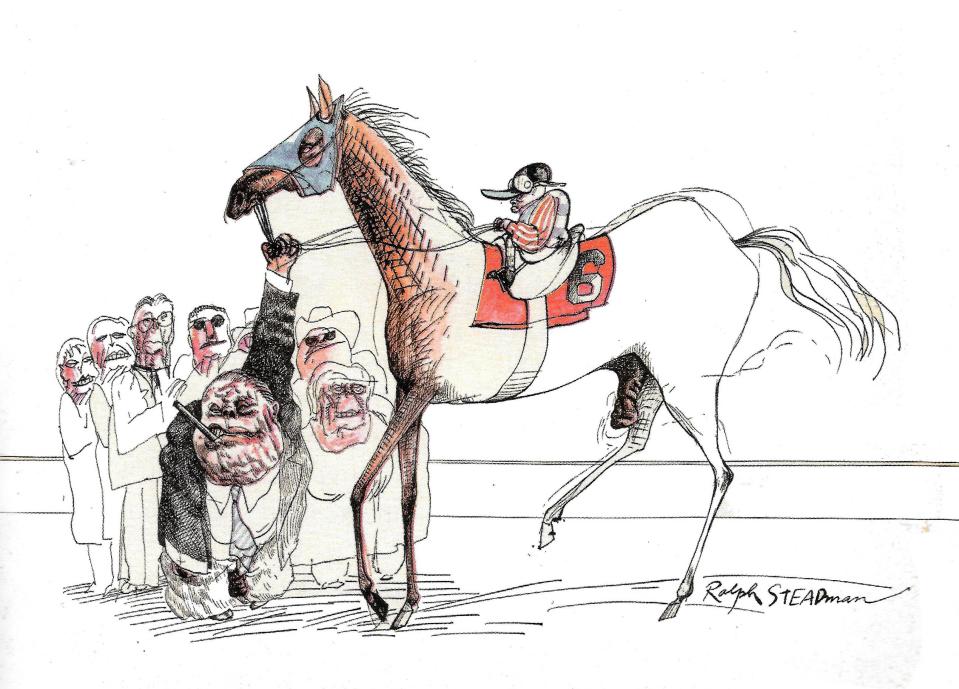

And, this year, Louisville produced three exhibits honoring Thompson. There was a “Thurby” day at Churchill Downs. “All my preaching all these years, it finally paid off,” said Whitehead. The Frazier’s “Freak Power” exhibit focused on Thompson’s run for Sheriff in Aspen (and included a replica of his kitchen). The University of Kentucky’s College of Fine Arts exhibit, Ralph Steadman: A Retrospective featured the collaborations between Steadman and Thompson for Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas, and the Speed Museum’s Gonzo! An Illustrated Guide to Hunter S. Thompson focused on Thompson’s work from 1965 to ‘74.

The Speed Museum is an immaculate, state-of-the-art facility located next to the University. Its Gonzo! exhibit was a compact collection of memorabilia: large format prints of Steadman’s and Tom Benton’s work, Annie Leibovitz photos of Thompson, and video interviews.

The day I visited, enormous bouquets were being affixed to exposed beams as a wedding party prepared to exchange vows near the Speed’s entrance, and a long folding table was set with single-serving bottles of bourbon, labeled with guests’ names. The gonzo exhibit, findable via Steadman-splatter decals on the concrete floor, opened with Steadman’s enormous and now-famous portrait of Dr. Gonzo, with the phrase “it never got weird enough for me” written to one side.

There was a self-portrait Thompson took after getting beaten up by the Hell’s Angels. Video clips played on an era-appropriate television in a corner of the room (with books cinematically stacked on top). In one clip, Thompson pulled the pin on a fire extinguisher, one of his calling-card stunts, in an editor’s office. And under glass, alongside Derby-day ephemera, was a letter he typed to Steadman after their collaboration, on June 2, 1970: “Dear Ralph…. You filthy twisted pervert I’ll beat your ass like a gong for that drawing you did of me. You bastard….. stay out of Kentucky from now on. And Colorado too…”

This year’s GonzoFest kicked off with an evening at the museum on the 19th of July (a day after Thompson’s birthday). The festivities included a panel discussion between Juan Thompson and Whitehead, moderated by WFPL President Stephen George. The Curator, Erika Holmquist-Wall, gave a gallery talk alongside Dr. Rory Feehan.

Flying into Louisville for the first time, Feehan said, “I saw that flat, green land. It was like Ireland in the sun.” Not unlike Kentucky, said Feehan, Ireland is known for whiskey and horse racing. Not unlike Louisville, Dublin had a contentious relationship with its own James Joyce, who is now very celebrated.

Thompson died over a dozen years ago, which for a historian, is no time at all. Already, though, there has been significant renewed interest and engagement with Thompson’s work. “In the last 15 years there has been an explosion of research papers,” said Feehan. As the Gonzoville movement builds momentum and academics fine-tune theories, reframing Thompson’s situation in literature, it makes sense to start defining his place in his hometown, too.

The goal, said Whitehead, is to have a permanent place for all things Hunter S. Thompson. A place that can showcase, and maintain, all of his personal archives.

There are many parties interested in the Thompson archives, and where they’ll eventually come to rest. (Johnny Depp owns a portion.) Will a multi-million dollar facility, like the Muhammad Ali Center, ever be built for them in Louisville? Right now it seems unlikely. But, as Lindenberger said, “If anybody can do it, Ron would pull it together.”

Ron Whitehead—the Outlaw Poet, as he calls himself—will be 69 years old this November. He cares deeply about Thompson’s work, and giving him his proper due in Louisville. He’s also ready to pass the torch. “I’ve been doing this for 25 years,” said Whitehead. “Juan [Thompson] has moved to town. I'm turning this all over to him. Everybody knows that I'm going to stay on top of whatever is going on. I'll work behind the scenes, but 25 years is enough. This is an ending and a beginning.”

Originally Appeared on GQ