Keeping connection: Hospitals in Bucks County, Montco work with babies, new moms in addiction recovery

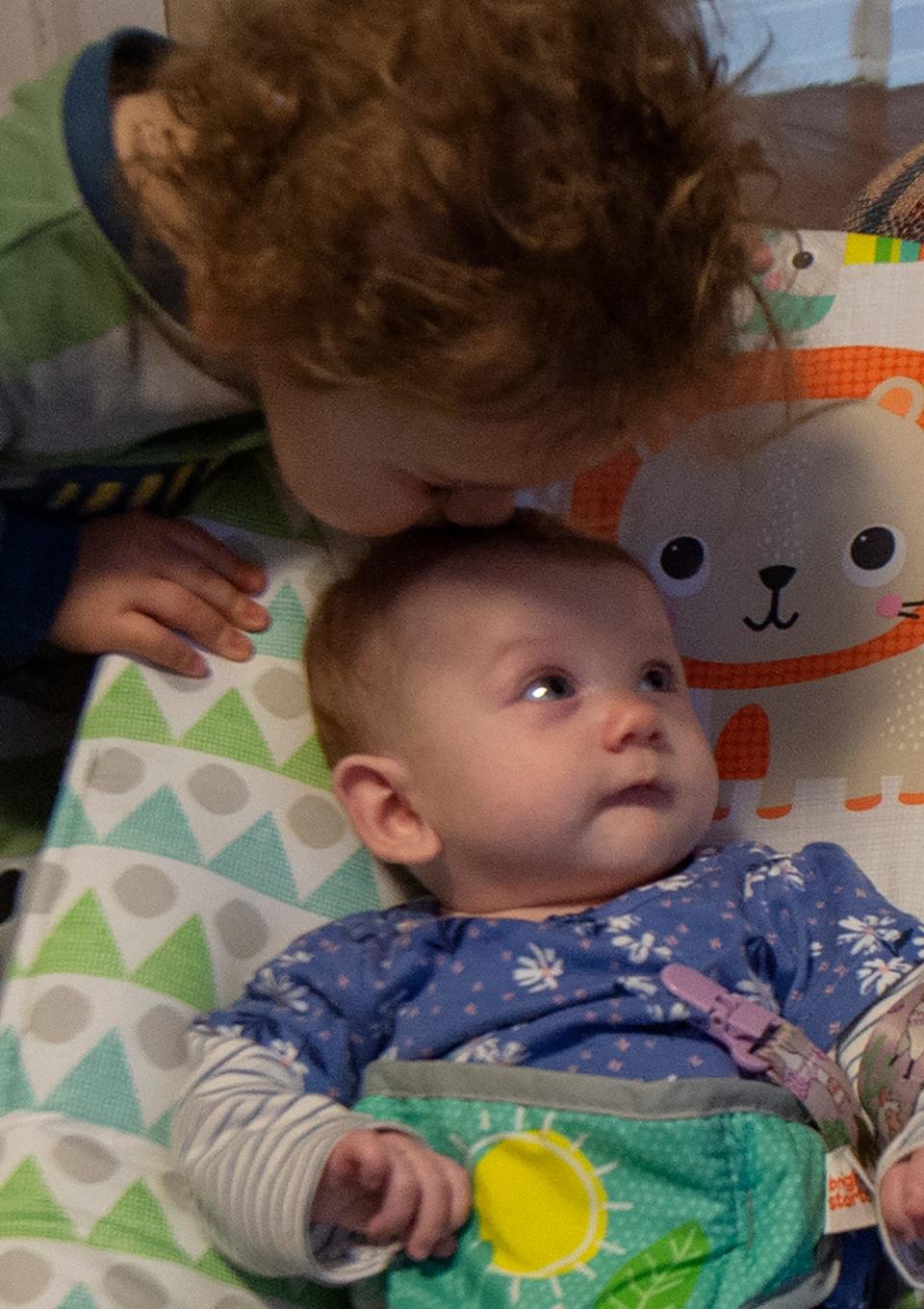

Little Noah loves his little sister. They’re only a year apart, but the 15-month-old already knows how to give Annalyce kisses, pat her hair and hold her tiny hand.

As their mom Patricia watches her babies, she knows she’s in a good place.

“Don’t give up” is her advice to other women who are drug addicted and trying to get clean. “When I look at where I’m at, this is what I was dreaming of when I was using and didn’t have my life together.”

For her and her children's privacy, the newspaper is withholding Patricia's last name.

Their apartment is small but her boyfriend has a job and she works part-time. She has been on methadone for over a year and a half and has delivered two healthy, alert and happy children. With assistance from Bucks County Children and Youth and Tabor Services, the family has a home and is thriving.

Bucks County Children and Youth is helping 1,985 families, including 3,518 children, with supportive services. Many of these families have or have had substance abuse issues. The agency is working in conjunction with several area hospitals that have seen an increase in the number of women giving birth to babies born with opioid withdrawal symptoms who need supportive care before and after they leave the hospitals.

The hospitals have found that if they can get mothers-to-be with substance abuse problems in treatment during their pregnancy and line up post-partum supportive services, there are many more success stories like Patricia's and fewer children end up in foster care, which is a last resort.

"The birth of a baby is a huge life event," said Kelly Gahan, manager of General Protective Services for Children Age 0-5 for Bucks County Children and Youth Services. "It throws a family into stress."

Even the expected can be difficult, she said. For example, a cranky, crying baby going through opioid withdrawal can be hard on a mother or parents who are trying to cope with their own issues in recovery.

It can be "a vulnerable time," Gahan said.

Good outcomes start with prenatal care

Prenatal and postpartum care is key to successful outcomes. Hospitals in Bucks and Montgomery counties try to identify pregnant women who have substance abuse issues during obstetrical visits and continue services until well after their babies are born. They also work in coordination with the county and state social services agencies to coordinate care to help the recovery process continue.

Specially trained obstetricians, pediatricians, counselors and social workers help so a mother can safely deliver a healthy baby and learn the parenting skills needed to care for their child, all while trying to overcome powerful addiction.

This is all part of a "Plan of Safe Care" that Pennsylvania requires as part of Act 54 of 2018 to ensure that parents who have or are recovering from substance abuse issues are helped in the care of their children.

A baby who experiences opioid withdrawal after birth is described as having Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome (NAS) or a newer term, Neonatal Opioid Withdrawal Syndrome (NOWS).

As the opioid epidemic has scourged the country, the number of babies born with addictions has increased in recent years. In Pennsylvania, there were 1,825 babies born with NAS in 2020, the most recent year for which data is available from the state’s Department of Health.

“The overall incidence rates across the state was 14.0 cases per 1,000 live births, an increase from the rate of 11.9 cases per 1,000 live births reported in 2019," said Mark O’Neill, DOH press secretary.

The use of a new “Eat, Sleep, Console” program is helping hospitals in Bucks and Montgomery counties, which also reported increases in the number of addicted babies in recent years, reduce the need for medications previously used to control infants' symptoms of opioid withdrawal.

Holy Redeemer Hospital in Abington delivers about 2,800 babies annually and cares for about 40 babies born with NAS every year. It recently received a visit from the United States Secretary of Health and Human Services Xavier Becerra and Congresswoman Madeleine Dean, as well as two federal grants totaling $849,142 to help fund its new NEST (Navigational Empathy for Substance Use Disorder and Treatment) program. This provides access to behavioral health counseling services and the support of a patient navigator to help addicted mothers.

“The opioid epidemic in the Philadelphia region has put so many moms and babies at risk,” said Anne Catino, Holy Redeemer Hospital’s chief nursing officer. “The funding gave us the capacity to support these patients with a trusted advocate who provides resources that strengthen their well-being. We now provide the services of a behavioral health counselor who offers in-person and telehealth services to these vulnerable patients.”

The hospital began offering expanded services in 2013 to help pregnant women both before and after delivery but the program now is seeing more patients.

“NEST navigators eliminate barriers to transportation, appointment scheduling, counseling, and childcare,” said hospital spokesman Rich Leonowitz in an email. “They connect patients with dietary consultants, parenting education and childbirth classes, early intervention services for non-insured families, recovery support activities, and translation of written support materials if a patient’s language of choice isn’t English.”

Catino said that Holy Redeemer has two obstetricians to whom women who are pregnant and addicted to opioids are referred and who can prescribe drugs to treat their addiction that are safer for the fetus.

St. Mary Medical Center in Middletown where Patricia delivered her babies, Jefferson Health-Abington, Doylestown Health and Grand View Health also have programs to assist pregnant women who are addicted to heroin or other opioid drugs.

The hospitals also are concerned about the new legalization of medical marijuana and how this could affect mothers who take these supplements while pregnant.

Support and treatments work in combination

The National Institutes of Health states that the prescribed use of methadone or buprenorphine for a mother addicted to opioids prevents the fetus from going through repeated withdrawal before birth and results in the baby having fewer problems going through NAS when born. Plus, the mother-to-be who is receiving treatment for both her pregnancy and her addiction is more likely to stay the course and be able to manage her own and her baby’s care after birth.

Swaddling the babies in low-lit rooms and “keeping the babies with their mothers so they’re together as a pair,” is so important, said Denise Ellison, a pediatric nurse practitioner and program coordinator for the Newborn Nursery Services at Jefferson-Abington. The hospital delivers about 4,000 babies a year and has a Level 3B neonatal intensive care unit (NICU), which can serve some of the youngest preemies.

Jefferson Health-Abington previously used a “Finnegan Tool” to rate addicted babies shortly after birth. If they scored eight or higher on the assessment — “if they’re jittery, not feeding well, feverish, showing signs of their skin breaking down” — the babies were given medication to ease their symptoms, but they had to be weaned off it eventually. With the new “Eat, Sleep, Console” protocol, they are comforted without medication or with reduced doses, based on their functioning.

“We found many of the babies who might have needed medicine or pharmacological treatment didn’t need it as they did before. It really integrates supportive care,” Ellison said.

The mothers are allowed to breastfeed their infants so long as they are in a program of prescribed medication, and not using illicit drugs. The hospital handles about five babies a month who are going through withdrawal.

Dr. Kathryn Ziegler, an Abington neonatologist, said that babies born addicted to opioids often have been exposed to other substances as well, such as nicotine, or cocaine. Cocaine doesn’t have the withdrawal symptoms of opioids but can cause complications in pregnancy such as a placenta that pulls away from the uterus and may cause the need for an early delivery.

St. Mary Medical Center in Middletown delivers between 1,600 and 1,700 babies a year. About three to four a week are in treatment for some type of substance abuse. Its Family Medicine Center in Bensalem provides care for pregnant and new mothers and their babies without regard for ability to pay.

“It’s a growing problem in the community,” said Dr. Prem Marlapudi, director of St. Mary’s NICU and chair of the Department of Pediatrics. The hospital previously used medication to ease the babies’ withdrawal symptoms and, like Holy Redeemer and Jefferson-Health Abington, it’s using the “Eat, Sleep Console” program to try to keep a newborn comfortable and connected to their mother. Fathers also can play a big role.

If medication is still needed, it’s given, but Marlapudi said allowing a mother to stay in a nesting room for up to five days after her normal discharge day has made withdrawal easier on her baby. Even though the hospital is picking up the tab for this service, which may not be covered by insurance, it is also more cost effective than keeping the infant hospitalized for a longer period without their mother nearby.

The hospital recently combined its former Mother Bachmann Maternity Center with its children's and adult health centers into the Family Medicine Center. Both mother and baby can continue receiving services there after discharge from the hospital.

Doylestown Hospital treated 12 babies with NAS last year and nine so far this year.

“Our case managers handle many of these patients and refer according to addiction issues. The infants are managed by CHOP (Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia) Neonatology that are here in the hospital 24/7,” said Sue Mineo, director of Maternal/Child Services.

"The incidence of NAS babies at Grand View Hospital in West Rockhill has decreased over recent years to less than five annually out of approximately 800 births. Grand View offers the 'Eat, Sleep, Console' method of caring for these babies so many do not require use of morphine for treatment," said Wendy Kaiser, hospital spokeswoman.

All the hospitals work with the families and with the county and state agencies, if need be, to ensure the health and safety of the babies going home. The more a mother can stick with a treatment and counseling program at the hospital where she chooses to deliver, the less likely there is need for government intervention in the care of the newborn, Catino at Holy Redeemer said.

Patricia, who fought addiction with prescribed methadone during her pregnancies, said she was lucky in that her babies didn’t have problems going through withdrawal and that she received help from Bucks County’s Department of Children and Youth and Tabor Services in finding a suitable apartment with a rent subsidy.

But it still isn't easy being a mother with young children. Patricia doesn’t drive, so she has to make sure she gets what she needs when transportation is available. Infant formula and diapers are just as necessary as milk and bread.

At Samara House in Coatesville, another woman from Bucks County, Rita, is going through drug rehabilitation.

Over a month ago, she went into labor early and was rushed to Chester County Hospital where she delivered a baby girl prematurely. The infant is her third daughter but the first born while she has been in a recovery center. The baby had to stay in the hospital for a few weeks after birth and be weaned from the methadone her mom has been taking. Now both are together at the special recovery center that takes mothers and their children.

"When you’re coming off an addiction, it’s stressful just for you. But when you have a child, it’s extra stressful,” Rita said. The “Mommy and Me” program at Samara House has provided the support she needs, the mom said.

Rita is grateful. She knows when she leaves Samara, she has a home with her parents who will help her and her daughters.

'Housing is part of recovery'

But not all women are so lucky.

Once a mother and her baby leave the hospital or rehabilitation center, they need a place to stay and ongoing support.

“That’s the challenge, after they come out of rehab,” said Lisa Sallad, director of Samara. “Homelessness after they come out of treatment — that's such a setback. Housing is a part of recovery. Housing is really a struggle for these women.”

Bucks County is piloting a "Pathways to Housing" program in conjunction with Christ's Home in Warminster, said Marge McKeone, executive director of Bucks County Children and Youth. It has helped two families so far and a third has been put up in a motel while awaiting other housing.

More:Bucks County officials hear from those on frontline of addiction about how to spend $45M in aid

Diane Rosati, director of the Bucks County Drug and Alcohol Commission, said the county commissioners in December expect to approve a comprehensive plan for use of funds the county is receiving from opioid settlements with drug manufacturers, and the plan includes "programs dedicated to women and children substance abuse, which are really important programs."

The county should receive $45 million over the next 18 years through the settlements.

Ultimate goal: Healthy babies

Pregnant mothers need to advocate for themselves and their babies from the beginning.

As a neonatologist, Ziegler said advice she would give to any woman who has used drugs and wants to have a baby or is already pregnant is to get prenatal care.

“Understand that people in health care want to help you. Reach out to your physician and seek prenatal care. ... We all want healthy, safe babies. We’re all going to meet a mom where she is and get her to the finish line.”

And that is "a healthy baby."

The goal is that the care from first visit to delivery and postpartum care is comprehensive and seamless, while also addressing underlying or contributing factors to addiction, housing instability and other issues that can hurt a mother's recovery.

When Jefferson-Abington holds its Plan of Safe Care meeting before a baby who has gone through withdrawal is discharged, it involves the parents, pediatrician, counselors and social workers who may be involved in ongoing care.

“It’s a warm send-off,” Ellison said.

Not all stories are successful, health care workers admitted. Some women have no family support. They may be living in a homeless shelter. They lack financial support or secure employment. Some fall back into addiction. And some babies end up in a cycle of foster care. But if mothers can keep up with their own treatment, they are better able to care for their babies.

Denise Centeno, practice administrator for St. Mary's Family Health, and Patricia Wood, a nurse practitioner there, say the hospital covers the cost of care until the parents and baby can get on Medicaid services if they qualify. In many cases, "kinship care" is provided to the baby while the mother continues in treatment.

"We see a lot of grandmothers in here," Centeno said.

That's why programs like NEST are so important , addressing and eliminating "barriers to transportation, appointment scheduling, counseling and childcare," Redeemer Health stated in announcing it received the grants from the United States Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.

For Patricia, and her young family, in Croydon, the struggle has been difficult, but recovery has been well worth it.

Patricia said that she and her boyfriend are reaching that goal.

"I have my kids and have a roof over their heads. I'm proud of myself. I don't know what I would do without them."

More:Montco and Bucks County hospitals urge vaccines as we could be in for a severe flu season

This article originally appeared on Bucks County Courier Times: Addicted babies, their moms find help through recovery at PA hospitals