Are Ken and Angela Paxton the next Ma and Pa Ferguson of Texas impeachment politics?

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

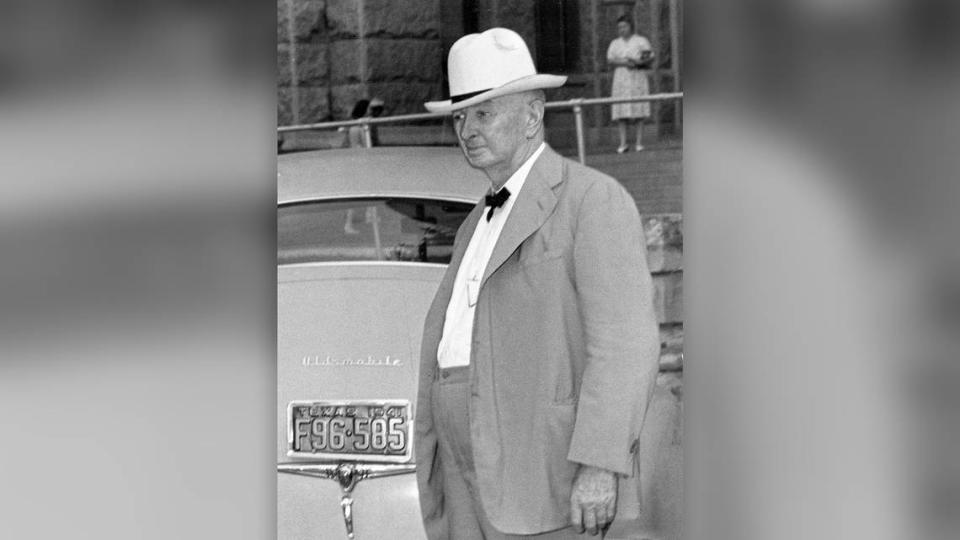

Two months after Gov. James “Pa” Ferguson’s 1917 impeachment and ouster from the state capital, the unrepentant chief executive visited the Fort Worth Stockyards, campaigning for his next run for office.

Nicknamed “Farmer Jim,” Ferguson operated a hog farm in Temple and ran into trouble by depositing $250,000 in state funds into a Central Texas bank that enriched his pockets. With his folksy manner and backwoods grammar, Pa was convinced Texas voters would forgive him and send his family back to Austin.

Voters ultimately did.

The Texas governor’s impeachment a century ago has drawn comparisons with the impending Senate trial of suspended Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton.

Paxton faced 20 articles of impeachment. Ferguson faced 21 and was convicted of 10 — among them three charges related to a feud with the University of Texas and five for financial shenanigans. Whereas Paxton stands accused of intervening on behalf of a wealthy donor, an Austin real estate magnate, Ferguson was on the take from the beer industry.

Paxton is free on $35,000 bond stemming from felony securities-fraud charges in Collin County, a case that pre-dates accusations of bribery. Before Pa Ferguson’s impeachment, a Travis County grand jury indicted him on nine criminal charges. The governor attributed one charge to a “bookkeeping error” and posted $13,000 bond.

Paxton’s sense of entitlement led him to ask the donor renovating his house to install granite kitchen counter tops, according to House impeachment investigators. Ferguson’s sense of entitlement surfaced when he billed the state $2,400 for platters of chicken salad ordered from the capital city’s Driskill Hotel. The matter was appealed to the state Supreme Court, which ordered Pa to pay.

Paxton billed the legislature for a $3.3 million settlement to four whistleblowers he had fired from the AG’s office. That prompted a Texas House committee to investigate, resulting in his May 27 impeachment. Paxton has denied the accusations against him.

Ferguson’s misdeeds were widely reported, yet there was little public outcry until he picked a fight with the state university. After he reshuffled the Board of Regents and vetoed the university’s $820,000 budget, angry alumni from UT’s powerful Ex-Students Association marched past the governor’s mansion singing “The Eyes of Texas” and hoisting placards that compared Ferguson to the German kaiser.

Pa Ferguson fought Prohibition, women’s suffrage

Folksy to a fault, Pa Ferguson was elected in 1914 on a tide of votes from tenant farmers who lived at the “forks of the creeks” and endorsed his pledge to fight Prohibition and women’s suffrage. A native of Salado, he was a country boy who married into money, became a banker, and ascended to the governor’s mansion on his first bid for public office.

He liked to boast that his diploma was from the “university of hard knocks.” As for his legal credentials, he passed the bar in 1897 by sharing a quart of Four Roses bourbon with judges administering an oral test. The jurists never asked the aspiring attorney a question.

Ferguson contended that the state university was run by smug administrators who belittled others as “barbs” — his lingo for barbarians. In a state with 4.46 million residents, 2,900 students attended the state university. Texas spent $282 per college student but a mere $4.50 per person for “poor children who picked cotton” and attended “little red schoolhouses.”

The governor was outraged to learn that some full-time professors taught less than 15 hours a week. Faculty who lectured around the state often brought along their families, who dined at university expense. They tallied travel expenses at 3 cents per mile — a half-cent higher than the customary rate for state employees.

“I have found more corruption in the affairs of the University of Texas than in all the other departments of state government,” railed the governor. “I have found far more disloyalty in the State University ... than among the Germans.”

A battle with the University of Texas

Targeting seven faculty, he picked apart their expense accounts and labeled them “butterfly chasers ... day dreamers ... two-bit thieves ... and educated fools.” Among those he attacked was folklorist John A. Lomax, a Harvard-educated Texan who salvaged from obscurity such ballads as “Home on the Range” and “Sweet Betsy from Pike.”

Ferguson castigated physicist William T. Maher, who crusaded against the capital’s bars and brothels, a threat to Ferguson’s financial backers. He objected to journalism department chairman William Mayes, editor of the feisty Brownwood Bulletin which “skinned the governor from hell to breakfast.”

Officially ousted from office Sept. 25, 1917, after a Senate vote of 25-3 to convict, Ferguson was barred from running for state office. That did not end his political career. He ran for president of the United States on his own party ticket, a losing proposition that kept him in the limelight. He lost a race for U.S. Senate in 1922, then in 1924, he ran his wife, Miriam Amanda “Ma” Ferguson, for governor. With Pa pulling the strings, Ma won in a runoff. Although she lost a bid for reelection in 1926, the couple was back in the governor’s mansion after the election of 1933.

Ma Ferguson’s entry into politics echoes another contemporary comparison. Angela Paxton, wife of the suspended attorney general, is a state senator. She will attend her husband’s Senate trial but will not be allowed to cast a vote. Although she is a math teacher rather than an attorney, she may someday seek higher office that, similar to Ma and Pa, keeps her family in Austin’s political whirl.

Hollace Ava Weiner, an author and historian, is director of the Fort Worth Jewish Archives. This column is adapted from a chapter titled “Faber vs. Ferguson: A Fight for Academic Freedom,” in Weiner’s book “Jewish Stars in Texas: Rabbis and Their Work,” Texas A&M University Press, 1999.