Ken Burns' new Hemingway documentary doesn't give you a reason to read Hemingway

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

In 1924 the critic Edmund Wilson did what critics are known to do on occasion: He heralded the arrival of a stunning new voice in American fiction. Reviewing Ernest Hemingway’s first two books, “Three Stories and Ten Poems” and “In Our Time,” Wilson celebrated the early short stories of a Midwestern-bred newspaperman who’d served in the Great War. His work was straightforward without being naive, Wilson wrote, clear-eyed without being didactic, precise about matters of war and foreign lands, pioneering in how deeply he got into the heads of his characters. “It is,” Wilson announced, “a distinctively American development.”

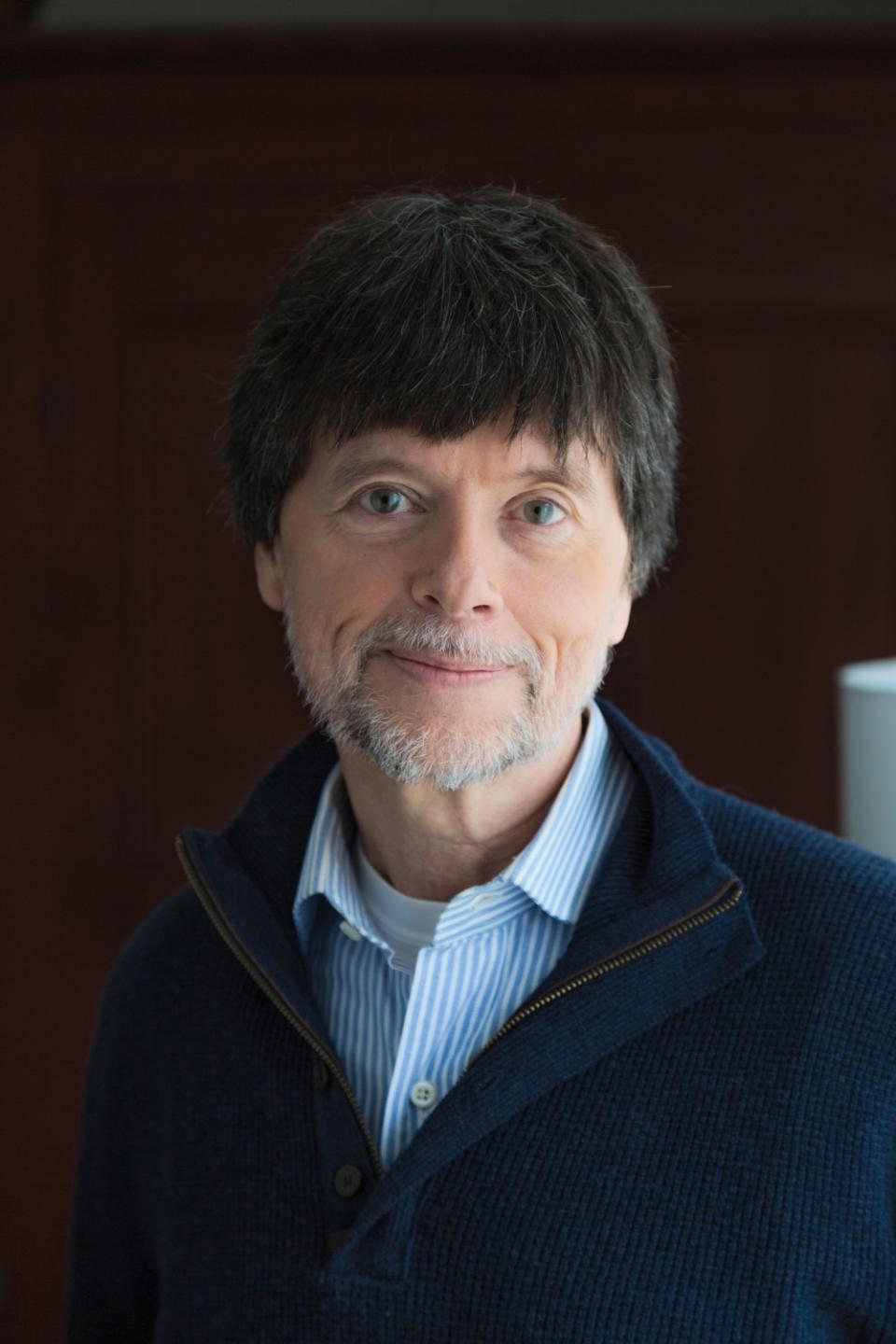

The template was set for Hemingway’s literary identity for decades to come: two-fisted, intrepid and unvarnished. That’s largely the story that gets told in “Hemingway,” a six-hour, three-part documentary by Ken Burns and Lynn Novick that premieres Monday on PBS. The directors ably capture the high points of the writer’s life and career: Midwestern upbringing, journalism, war service, literary fame, romantic failures, fishing, drinking, Nobel, more drinking, decline, self-inflicted gunshot wound in Ketchum, Idaho, in 1961. They make the case for a great American life, with all the familiar comforts of a Burns production — slow pans across sepia-toned photos, sober narration (by Peter Coyote) and avuncular talking heads.

What they don’t do is make a case for him as a great American writer. That’s a harder task these days.

Reading Hemingway in 2021, nearly a century after Wilson launched him, can feel more like an archivist’s duty than engagement with a vibrant literary force. Some of the reasons for that are of the #CancelPapa variety: invocations of the N-word and macho heroes lamenting the “bitchery” of the women around them. And for all his far-flung experiences in the Caribbean, Europe and Africa — worked into stories and reportage that now carry a whiff of outdated exoticism — he could be thematically one-note. So many of his stories turn on his manly protagonists soggily discovering that they’re vulnerable or trying not to admit that they are. (“I feel as though everything has gone to hell inside of me. I don’t know, Marge.”)

Yet Hemingway’s obsolescence isn’t just a matter of cultural politics; it’s a consequence of his success. Literary culture has so deeply sublimated what’s meaningful about Hemingway, and expanded beyond it, that it hardly requires Hemingway himself.

The theme of brooding masculinity, first presented to a shell-shocked society in a time of World Wars, is now just one of many traumas writers are free to explore. His vaunted baby-shoes-never-worn simplicity is valuable — Joan Didion famously taught herself to write by copying his stories. But rigorous simplicity isn’t always the exemplar of great writing. (Among Papa’s contemporaries, wooly William Faulkner’s stock is much higher at the moment.) As for his cultural tourism, global literature now offers us what he couldn’t — the view from inside. No need to wait on a sermonizing dispatch from the Great American Lion of Letters.

Presumably, Burns and Novick disagree. (A companion anthology for the series, “The Hemingway Stories,” was published last month.) But while nobody could’ve expected “Hemingway” to go deep on literary criticism, it’s surprising how little the documentary attempts to advocate on behalf of Hemingway as a writer or to argue why we might read him today.

This is partly a function of the commentators assembled. Biographers and literary historians abound, but the most enthusiastic advocate for Hemingway’s 1940 novel of the Spanish Civil War, “For Whom the Bell Tolls,” is the late Sen. John McCain, who modeled himself on the novel’s hero, Robert Jordan. The fiction writers who appear — among them Tobias Wolff, Mario Vargas Llosa, Edna O’Brien and Abraham Verghese — are somber and sometimes ambivalent about Hemingway’s work. (Llosa cackles at a sex scene in “Tolls”; O’Brien dismisses “The Old Man and the Sea.”) If any writers have emerged in the past three decades who claim Hemingway as a key inspiration, Burns and Novick didn’t put them in front of a camera.

One reason may be that despite the supposed timelessness of his prose, Hemingway’s style was largely the product of a particular Modernist moment. As the documentary notes, he was part of a movement that often prized obscurity — Ezra Pound’s gnomic poems, Gertrude Stein’s redundant prose — and gave it a more colloquial, less artsy feel. Unlike James Joyce and Virginia Woolf, his early plots were decidedly low-concept, dealing in domestic dramas in Michigan or bitter warfare in Europe. His directness, along with his sense of characters’ subjectivity, felt new in the era following Henry James and Theodore Dreiser. (This was the “distinctly American development” Edmund Wilson was talking about.)

And now? Telling an aspiring writer to privilege crisp dialogue and an interior sense of character is like insisting toddlers study cuneiform before learning their ABCs. It’s a sensibility baked into American literature, and Hemingway’s oeuvre isn’t necessarily the best place to learn it. Think of a story like “Big Two Hearted River,” in which the trauma Nick Adams feels after a wildfire and the loss of a friend is heavily suppressed; instead, Hemingway unspools an overextended yarn about the revivifying power of nature, with an affected Stein-for-dummies rhythm. (“He was sleepy. He felt sleep coming. He curled up under the blanket and went to sleep.”) Hemingway used those loping beats at climactic moments in his novels, but they can often feel like forced melodrama. For all its vaunted simplicity, a hallmark of much of Hemingway’s work is bloat.

The story of American literature in the last half-century has been about getting out from Papa’s shadow. The ’60s brought a candor about sex — not to mention humor — that often escaped Hemingway. The dirty realists of the ’70s and ’80s shaved off the repetition and sharpened the domestic drama. Toni Morrison expanded the rhetorical gambits available for writing about the Midwest; Cormac McCarthy did as much for the Southwest. The closest thing we have to a prominent “Hemingwayesque” author today is Dave Eggers, who deployed that clipped-yet-redundant style in novels like “A Hologram for the King” and “The Circle.” But as a stylist, he’s an island unto himself.

When the documentary does directly engage with Hemingway’s writing, it celebrates his sentences, not the breadth of his work or depth of his themes. Which may be the best way to think about him now. His sentences are often perfect brushstrokes. The exchange in “Indian Camp” between the doctor and his son, who’s just witnessed death for the first time. (“Is dying hard, Daddy?” “No, I think it’s pretty easy, Nick. It all depends.”) A woman’s agonized demand in “Hills Like White Elephants” that goes off like a bomb blast: “Would you please please please please please please please stop talking?” The beautifully calibrated, nearly biblical decline of the stubborn fisherman in “The Old Man and the Sea,” as a curtain slowly falls over his life’s labors: “In the dark now and no glow showing and no lights and only the wind and the steady pull of the sail he felt that perhaps he was already dead.”

Hemingway strove to write “one true sentence,” he once said. It’s clear what that meant for him, and he often achieved it. But other writers have found other, better ways to write sentences and other, better ways to be true.

Athitakis is a writer in Phoenix and author of “The New Midwest.”

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times.