Kenny and me: A colleague and former student salutes Kenneth Turan as he leaves The Times

They say you should never meet your heroes. They’re wrong. I’m grateful not only to have met one of mine, but also to have called him my teacher, colleague and friend.

There is some consolation in this, and this is a time for consolation. This week, after nearly 30 years on the job, Kenneth Turan is stepping down as film critic for the Los Angeles Times.

He has assured us that we have not seen the last of his words, which is comforting if hardly surprising. For someone who spent years as a sports and features writer at the Washington Post — and who has tirelessly juggled book reviews, covered movies for radio, taught journalism classes and cranked out several books, all while holding down one of the most distinguished careers in film criticism — retirement was always going to be a relative concept. But he will no longer be writing movie reviews, the ones he has been churning out week after week since 1991, and which have been among the indispensable treasures of this newspaper.

I began devouring those reviews long before I ever thought I’d meet their author. I imagine that for most people, a love of film criticism grows out of an all-consuming love for movies; for me, the two loves evolved in tandem. I didn’t go to the movies terribly often as a kid growing up in Orange County, but my family did have a Times subscription, and I became an avid reader of film reviews. I got to the paper too late to read the great criticism of Times veterans like Charles Champlin, Sheila Benson, Peter Rainer and Michael Wilmington (that would come later), though not too late to appreciate Kevin Thomas' insightful and voluminous work.

As for the Calendar section's other “K.T.” byline, it soon became a weekly addiction. I read Kenneth Turan on the movies I saw, but also on the many, many more that I didn’t. His reviews and essays were my first cinematic education, and an education of the most pleasurable kind; they projected authority, to be sure, but that authority was always worn lightly, with sly humor and easy, unfussy grace. Kenneth — though to those who know him, he will always be simply, unforgettably “Kenny” — beckoned his readers into a conversation. He helped me make sense of what I loved, what I didn’t love and why the difference mattered.

I came to know what Kenny loved in movies: depth of emotion, complexity of character, a mastery of filmmaking that was both audacious and unobtrusive. I learned pretty quickly that he was a writer who truly loved words: the sparkling wit of Preston Sturges and Joseph Mankiewicz, yes, but also Shakespeare plays, Jane Austen novels and “the passionate, yeasty language” of Yiddish, whose long-buried literary and cinematic treasures were among his deepest passions.

Naturally, I also became familiar with Kenny’s cinematic pet peeves and inevitably adopted a few of them myself: phoniness, archness, empty formalism, nihilistic violence, willfully irritating characters. His pans were wickedly funny, as you know if you’ve read him on, say, “A Time to Kill” (“[Joel] Schumacher directs as if nuance were a capital offense”), “Very Bad Things” (“about as profound an experience as stepping in a pile of road kill”) or “In the Company of Men” (“the celluloid equivalent of a ’round-the-clock news station that offers all jerks, all the time”). And I’ll never forget his litany of complaints about Lars von Trier’s polarizing “Dancer in the Dark“: “awkward writing, bungled acting, intentionally ugly cinematography, costar Catherine Deneuve dressed in the kind of threadbare shmattes my old aunts used to wear.”

Or his exquisite recommendation to the motion picture academy after it failed to nominate “Red” for foreign-language film and “Hoop Dreams” for documentary feature: “If the members of those branches knew the meaning of the word shame they would now be making arrangements for group suicide.”

His impatience with dramatic clichés and tin-eared dialogue lay at the heart of his intense dislike of “Titanic,” leading to a legendary dust-up that every Turan tribute is obliged to acknowledge — and why not? James Cameron’s angry letter to The Times, all but calling for the paper to fire him, remains the ultimate badge of film-critic honor. “Turan’s critical sensibility is the worst kind of ego-driven elitism,” Cameron seethed. “Poor Kenny. He sees himself as the lone voice crying in the wilderness, righteous but not heeded by the blind and dumb ‘great unwashed’ around him.”

There’s no point in relitigating this 23 years later; Kenny didn’t need defending then and hardly needs defending now. But even as someone who personally loves “Titanic,” I have to say that he judged the movie much more fairly than Cameron judged him. Lone voice in the wilderness? You need only read Kenny, or spend a minute in his company, to know that he sees himself as no such thing. On the contrary, his companionability as a critic is the very thing that makes him so persuasive. He has always been honest about the tightrope walk that movie criticism often requires, that deft balance between the commonalities of audience experience and the idiosyncrasies of individual taste.

He has often noted the inherent loneliness of the profession, but there’s no arrogance or superiority in that acknowledgment. When he once wrote, “I am who I am, what I like and dislike is what I like and dislike” (in an essay headlined “Film Critic, Review Thyself”), he wasn’t speaking just for himself, but for all of us. We are all lone voices, Kenny reminds us, and our tastes, impressions and insights will always be more unique and complicated than studio formulas and box office grosses would have us think.

But while Kenny has never seen his words as irrefutable gospel, there is a touch of the evangelist to him. The “Titanic” contretemps notwithstanding, he fervently believes in Hollywood’s potential for greatness, for the kind of thrillingly intelligent popular filmmaking — “The Fugitive,” “L.A. Confidential,” “The Lord of the Rings,” “The Dark Knight” or “Black Panther” — that the studios at their best can accomplish. His commitment to the riches of independent, non-industrial cinema from all over the world, and his staunch advocacy for documentaries and animated films in particular, are no less impassioned. Like all great critics, he is less interesting for what he’s hated than for what he’s loved.

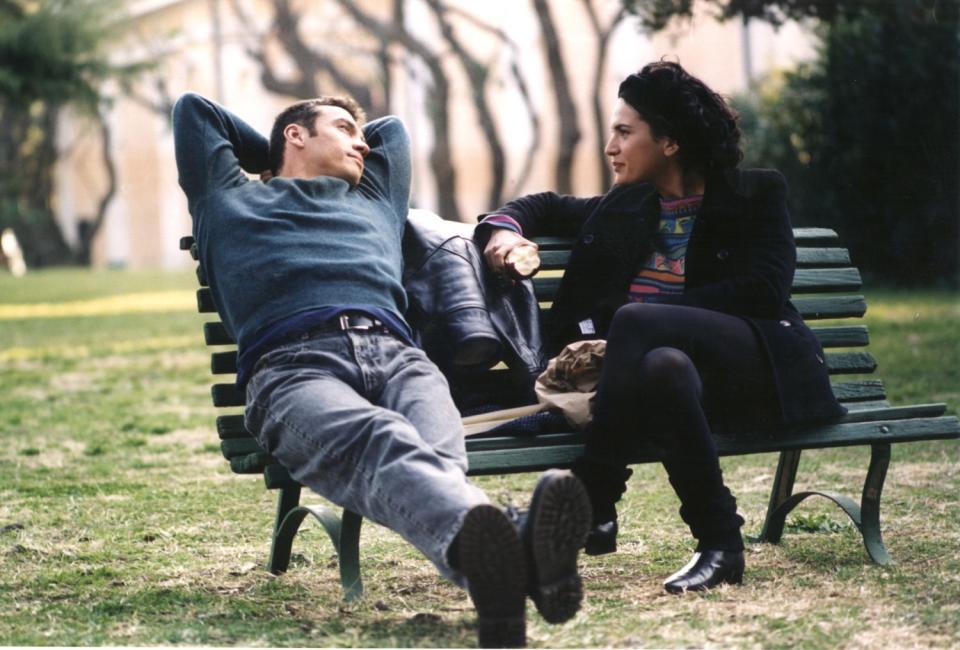

Those who have followed his work for years will know of what I speak. I’m thinking of the many who were persuaded to see Jane Campion’s “The Piano,” Atom Egoyan’s “The Sweet Hereafter” or Lynne Ramsay’s “Ratcatcher” after Kenny named them the best films of their respective years. Or those who, like me, showed up at the Laemmle Royal on opening weekend of “The Best of Youth,” drawn to this magnificent six-hour Italian epic by Kenny’s tantalizing rave: “It is that satisfying, that engrossing, that good.”

Maybe Kenny got you hooked on Mike Leigh or Errol Morris or Hayao Miyazaki. Maybe you discovered your own love of classic French cinema after his glowing essays on “Casque d’Or,” “The Earrings of Madame de … ” and “Children of Paradise.” Maybe you’ve taken issue with his ambivalence on Terrence Malick and Quentin Tarantino, or find his general aversion to horror movies totally off-base. That’s OK too. You haven’t fallen in love with a critic until you’ve disagreed with him or her intensely — and still find that you can’t stop reading.

If I had never crossed paths with Kenny personally or professionally, his work alone would have left a lasting impression. But the fates were kinder. As a journalism student at USC, I couldn’t believe my good fortune at being able to take Kenny’s workshop in film criticism in the spring of 2004. I still recall the thrill and the intimidation of that first class, and I tried to compensate for my anxieties as any desperate-to-impress amateur would: by acting like I knew more than I did. It didn’t matter. Kenny was grateful for engagement but immune to bluster, and he treated his students equally, whether their interest in criticism was casual or intense.

At the beginning of each class Kenny would bang a gavel and call roll — he was a creature of habit and delighted in these old-school rituals, he would always tell us — and then have us go around and read our reviews aloud. His feedback was judicious and precise, his compliments as sincere and thoughtful as his corrections. But even as he took us through his own thought process in shaping a review week after week, he always encouraged us to approach the movie in our own voices, and with our own ideas firmly in hand. Agreement or disagreement was beside the point; the point was to go deeper into the movie and engage the mirror it held up (or didn’t hold up) to the world. That was the beauty of writing about the movies, Kenny liked to remind us: You got to write about everything.

Kenny never stopped teaching me, even after I stopped calling him Professor Turan. Shortly before I graduated, he bought me lunch at The Times’ old offices downtown and helped me consider my options in the tough-to-crack world of entertainment journalism. He was always ready with a warm word, invariably signing his emails with a sweetly encouraging “hang in there.” (My friend and former Times colleague Steve Zeitchik and I still text each other an occasional “hang in there” in Kenny’s honor.) After I got a job as a copy editor and film reviewer at Variety (working under another critic legend, Todd McCarthy), I found myself bumping into Kenny and his wife, Patty, at screening rooms around L.A. I’d see him at festivals too: riding a shuttle at Sundance in his familiar green parka or lining up for a screening at Cannes in a white blazer, always with a hug and a smile at the ready.

Sometimes I had to pinch myself to acknowledge that someone I’d read and admired since my teenage years had become a mentor and a comrade. I pinched myself harder some 12 years later, in 2016, when The Times hired me as a movie critic. I recall wondering during those surreal early days of having work lunches with Kenny, poring over review assignments together, mulling the logistics of festivals and top-10 lists and conversation pieces: Was it weird, sharing a title and sometimes a byline with my old professor and longtime hero? Was it weird for him? It didn’t matter. From Day One, Kenny made clear, this was a working partnership that fortunately also happened to be a friendship. We were in this together, from beginning to end.

And now, four years later, the end is here. I’m grateful that Kenny is leaving on his own terms, which is not something that can be said of the innumerable great arts critics who have lost their jobs over an extraordinarily tumultuous period in American journalism and at The Times in particular. But neither Kenny nor anyone could have anticipated that his departure would coincide with a coronavirus pandemic that has so completely upended the way we live. For me, it’s wrenching — and also sadly fitting — that the writer who first taught me about movies is leaving at a moment when the movies themselves have gone dark. They will be back, of course, and Kenny’s words will be back as well. But things will never be the same.

A couple of years ago a reader emailed me, taking issue with a self-deprecating remark I’d made in an essay. “Ken’s shoes are big,” he wrote, “and shrinking your footprint isn’t the best way to fill them.” It was somehow both harsh and kind, both right and wrong. Kenny’s shoes aren’t just big; he’s the only one who could possibly fill them. The shoes he taught me and so many others to fill were not his, but our own.

Be blessed, Kenny. Never stop writing or watching movies (as if). Never stop showing us all how it’s done. Hang in there.