Kentucky once led the U.S. in this crop, later banned. What to know about the history

When advocates ramped up efforts to revive industrial hemp as a legal crop in Kentucky in the 1980s, the precedent stretched back two centuries.

Settlers beyond the Appalachian Mountains grew hemp on a small scale to get fiber for homemade thread, rope, textiles and other products.

Archibald McNeill grew the first crop in Kentucky in Boyle County in 1775, 17 years before Kentucky became a state.

The invention of the cotton gin in the early 1790s, however, created the opportunity for hemp to become a major cash crop for Kentucky farmers and manufacturers, which ultimately contributed to the spread of slavery in the state.

Before the cotton gin (short for engine) came along, it was hard to separate the seeds from the fiber in the type of cotton grown in the Deep South. The new machine solved that problem, leading to a boom in cotton-growing in the region.

Bales of cotton weighing hundreds of pounds had to be bound with something to be shipped to the East Coast and Europe.

With rich soil and a climate favorable to hemp, and access to deliver goods to Southern markets by river, hemp grown in Kentucky and processed into bagging and rope filled that need.

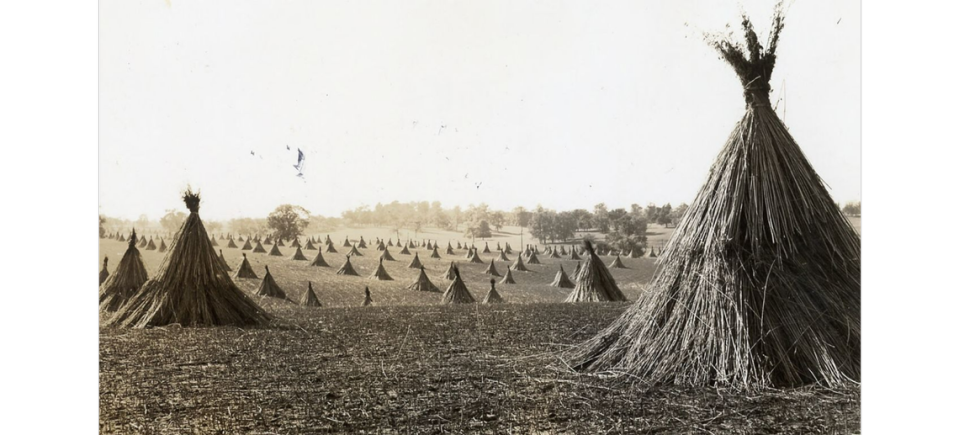

Hemp growing and processing flourished in the Bluegrass region in Central Kentucky.

“The inhabitants [of Lexington] now turn their attention almost entirely to the cultivation of hemp, for which they find their soil adapted, and which is more profitable than anything else they can cultivate,” a visitor wrote in 1810, according to James F. Hopkins’ 1951 book, “A History of Hemp in Kentucky.”

Facilities to turn fiber from the plant into bagging, rope and other products were concentrated in the Lexington area as well.

Kentucky’s status as a leading hemp producer played a key role in promoting slavery in the state.

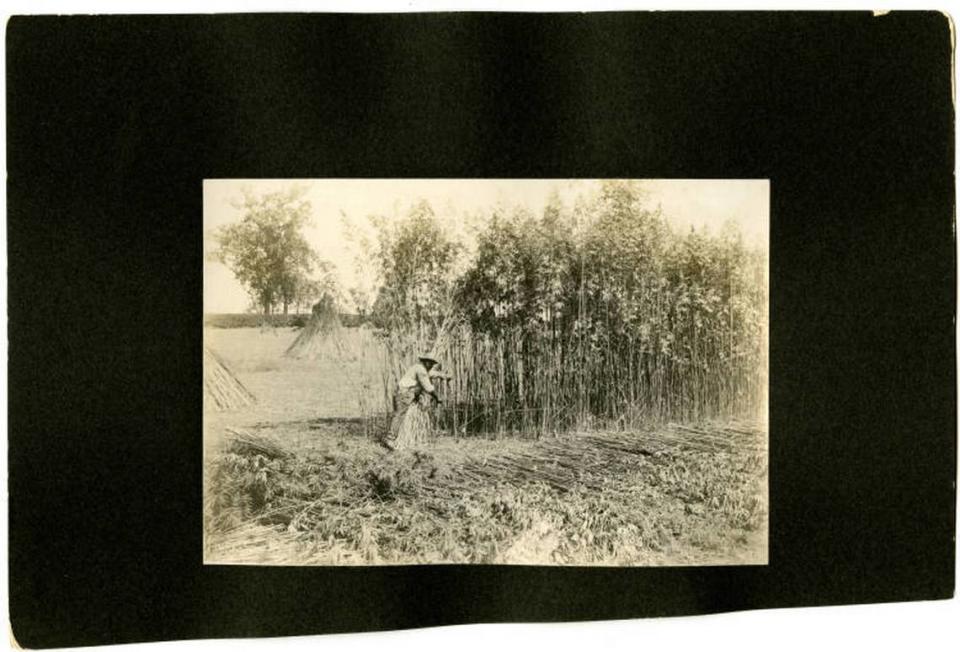

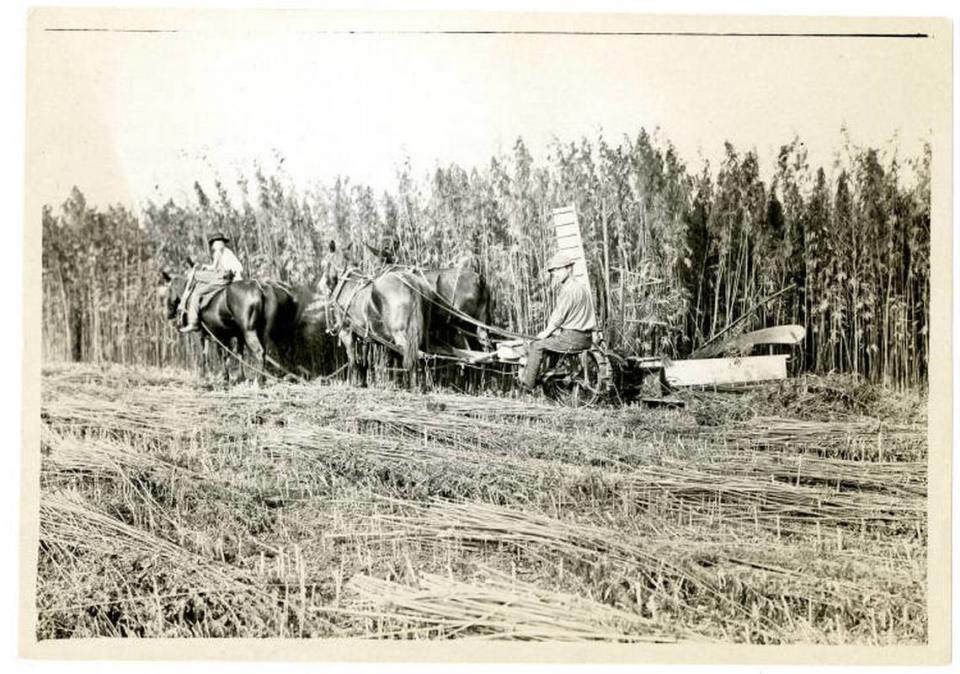

Growing hemp and turning it into finished products is labor-intensive, and farmers and factory operators used enslaved people for most of the work.

That included one of Kentucky’s best-known politicians of the 1800s, Henry Clay, who grew hemp at his 600-acre Ashland estate in Lexington and promoted the interests of the crop in Congress.

Clay enslaved at least 122 people during his life, according to the estate.

Historians have said that slavery probably wouldn’t have been as extensive in Kentucky without the hemp industry.

Farms that used slaves produced 95% of the hemp sold by Kentucky residents in 1860, University of Kentucky professor Steven A. Channing wrote in his 1977 book, “Kentucky: A History.”

Kentucky led the nation in hemp production through the first half of the 1800s, but with the cotton market cut off in the Civil War, demand for the crop declined in the 1860s and never fully recovered.

The reasons included competition from hemp grown in other states and countries, and a switch by the cotton industry to using other materials to bind bales.

Another was emancipation, which meant labor shortages for farm owners because there were no enslaved people to grow the crop and break the stalks to get out the fiber.

Kentucky farmers gradually switched to growing more profitable tobacco.

An 1894 report on farming in the Bluegrass said that tobacco was “taking the place of the one-time favorite — hemp — as a money crop,” Hopkins said in his book.

There was an upturn in hemp production in Kentucky and the U.S. when World War I cut access to hemp from Russia and Italy, but production dropped again after the war.

Shortly after the war, a staffer at the Kentucky Agricultural Experiment Station wrote, “Opinion seems to prevail at the present time that the hemp industry is a thing of the past and that the stable demand for the fiber has been usurped by other fibers imported from foreign countries,” Hopkins reported.

There was another short resurgence in Kentucky hemp in World War II, encouraged by the government to supply the war effort, but for decades that was the last gasp of the industry that once dominated Kentucky’s farm economy.

The Kentucky River Mills in Frankfort, which made rope and twine, was the last hemp factory to operate in the state. It closed in 1952.

“At the end of World War II the hemp industry in Kentucky appeared to have vanished. In time of stress, however, when fiber is needed and prices are high, it may appear again,” Hopkins wrote. “Once more perhaps the distinctive odor of growing hemp will hang heavily in the summer air, and the fields of emerald green may once again add beauty to the Kentucky landscape.”

That seemed unlikely for decades, however, largely because of hemp’s association with marijuana.

States began moving in the 1920s to outlaw marijuana, driven in part by misinformation about the dangers of the drug — the nation’s top drug officer testified at one point that smoking one joint could cause homicidal mania — and by prejudice toward Mexican immigrants and Black people, who were associated with marijuana use.

Congress ultimately put marijuana and hemp in the same class of drugs as heroin.

Hemp advocates pushing for a return of the crop as a way to boost the farm economy faced an uphill battle.

When then-Gov. Brereton Jones appointed a task force in November 1994 to study the issue, the panel abruptly disbanded after two meetings.

“I think the bottom line, quite frankly, is there is no reason to believe for a minute that you could produce hemp under the existing laws of the United States,” Joe Wright, a former state senator on the panel, said at the time.

But a decline in tobacco farming, furthered by the end in 2005 of a federal program that had supported tobacco production for decades, ultimately helped create traction for efforts to find another cash crop for farmers.

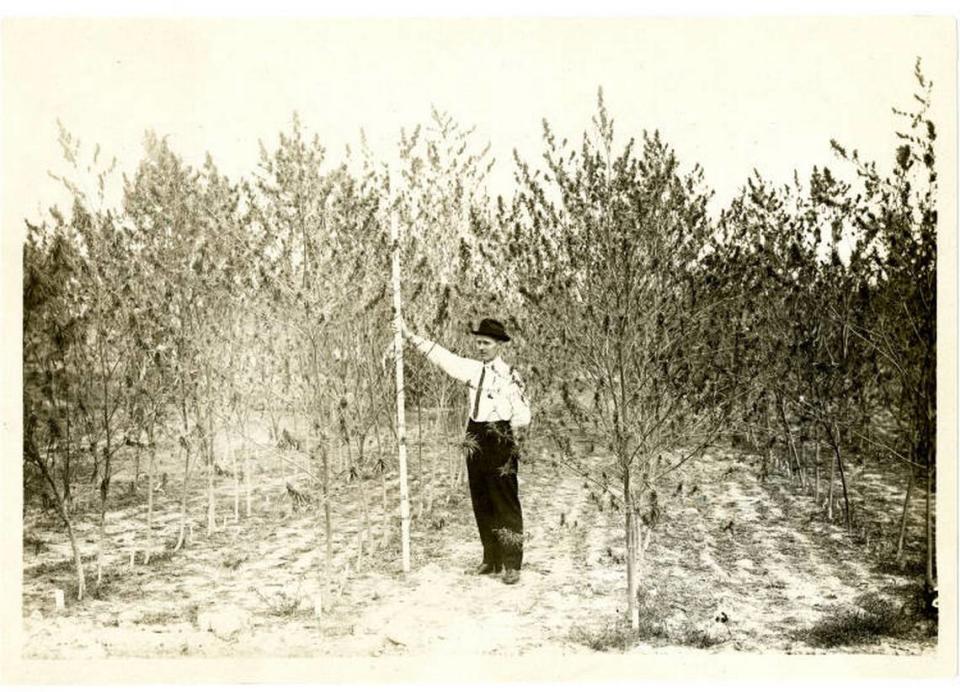

In 2013, Kentucky legislators approved a law that set up a system to grow hemp in Kentucky if the federal government OK’d hemp production.

The next year, Congress started down that road, authorizing pilot hemp crops through universities and state agriculture departments.

In the follow-up 2018 farm bill, Kentucky U.S. Sen. Mitch McConnell, then the Senate majority leader, pushed through a landmark change federal law on hemp, removing it from the federal list of controlled substances after nearly 50 years, making broader production possible.

“I am confident the ingenuity of Kentucky’s farmers and producers will find new and creative uses for this exciting crop,” McConnell said in December 2018. “We are at the beginning of a new era, and I cannot wait to see what comes next.”

▪ Sources: Kentucky Hempsters; Kentucky Historical Society; Ashland: The Henry Clay Estate; A History of Hemp in Kentucky, by James. F. Hopkins, 1951; Hemp & Henry Clay: Binding the Bluegrass to the World, by Andrew Patrick, Register of the Kentucky Historical Society, Vol. 117, No. 1 (Winter 2019); A New History of Kentucky, by Lowell H. Harrison and James C. Klotter, University Press of Kentucky, 1997; Kentucky: A History, by Steven A. Channing, American Association for State and Local History, 1977.