Kentucky school marks 50 years of helping kids who don’t fit in traditional classes

Logan Lafferty is a go-getter.

At age 18, the cheerful high school senior has his own landscaping business, is on the archery team and is taking classes to become a welder. He once struggled in math, though, sometimes making Ds.

That turned around after he switched from a large public high school to the David School as a junior. He makes As in math now.

“It surprised me big time,” Lafferty said.

The David School has been creating those stories for 50 years.

Young people looking to help in a poor corner of Appalachia founded the private, non-profit school in David, a former coal camp in Floyd County.

Classes started in January 1974.

The school helps high school students who have struggled in larger public schools for various reasons, including bullying, falling behind in classes or feeling like they just didn’t fit in.

They benefit from the close-knit spirit at the David School and more one-on-one instruction.

The school, which relies mostly on donations to operate, has helped hundreds of students finish high school.

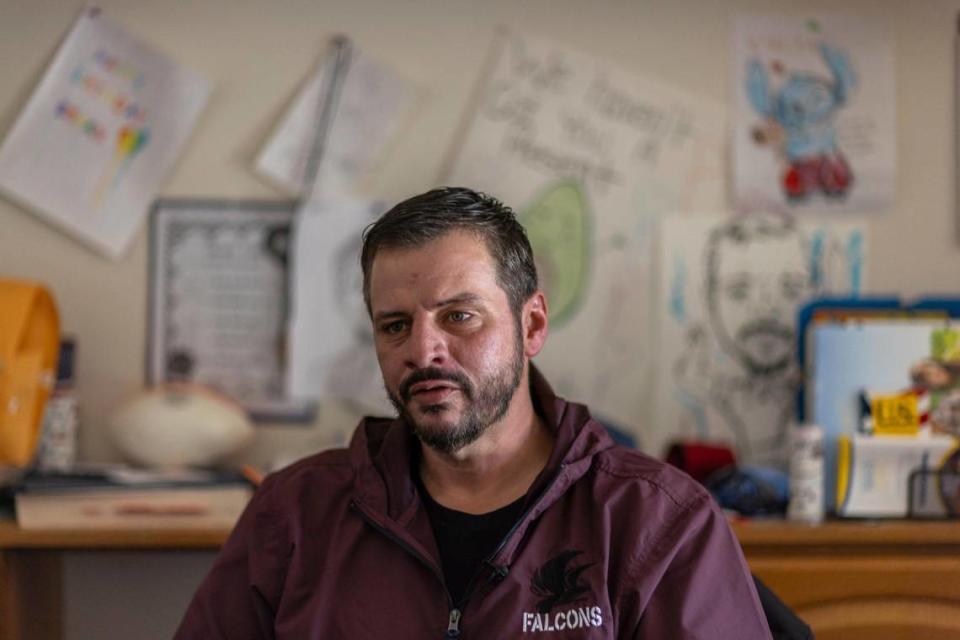

Bryan Lafferty, the principal, alls the school a safety net.

“I think without us they’d fall through the cracks and wouldn’t graduate,” he said of many of the students.

‘A lot of hands-on’

Every student does service work in the community, which has included visiting a nursing home, picking up litter and cleaning up a park. Students help with chores at school, including cleaning up, helping prepare food and maintaining the grounds.

There is no charge to attend the school, though students raise their own money for a senior trip, which has been to the beach the last few years.

Many students are from low-income families, and some have dealt with difficult situations at home.

Lafferty said students can get more personal attention at the school than in larger public high schools where teachers might have 30 or more kids in a class.

There are 10 to 15 students in a class at the David School. Teachers work with students on life skills as well as academics.

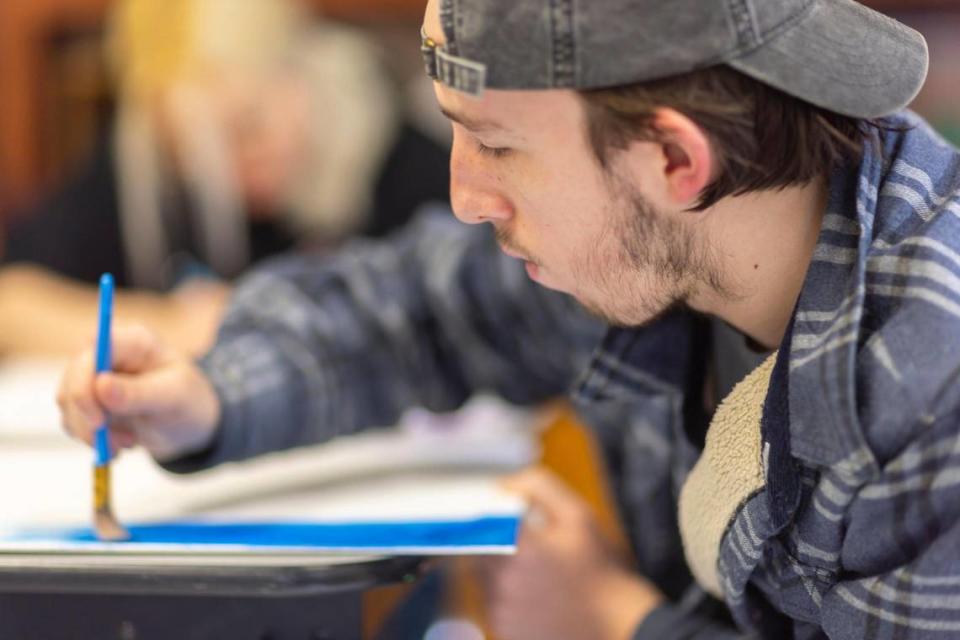

“They get a lot more one-on-one and a lot of hands-on” instruction, said Gladys Wireman, who teaches English, art and forensic science at the school.

‘Booming little place’

The community of David is like many other former coal towns in Eastern Kentucky that flourished at one time before declining as mines played out or became less profitable to operate.

The Princess Elkhorn Coal Company, formed in late 1940, built the town from scratch to serve its mines, according to a history by author Mary A. Pineau.

The town was named for a company executive.

In its heydey, the community had a pool, a theater, baseball fields, a soda fountain, a well-stocked store, an airfield and as many as 600 jobs, Pineau wrote.

“It once was a booming little place,” said longtime resident Jackie Howard, 73.

Princess Elkhorn shut down in 1968 and sold the town. The company’s coal reserves were high in sulfur and so less marketable, said Howard.

The new landlord didn’t keep up the water and sewer systems, according to Pineau’s history, and with those problems and the loss of jobs, the town dwindled.

The shutdown at David followed years in which the coal industry in Eastern Kentucky had been down. Coal production in the region hit a post-World War II high of 47 million tons in 1947, and didn’t top that number until 1970, according to the Kentucky Geological Survey.

More than half the people in some Eastern Kentucky counties in the 1960s were considered poor under federal income standards. National attention to the issue brought many idealistic young people to Eastern Kentucky in hopes of helping people through programs such as teaching and repairing homes.

Daniel Greene was a college freshman from Brooklyn when he visited Eastern Kentucky in 1968 to “do an Appalachia tour,” as he told the Herald-Leader in 1989.

Greene, the catalyst for starting the David School, told an interviewer he felt “called to come back and really make a difference,” after college.

Starting a school

Greene and others started the David School in the former coal-company commissary.

There were 10 students at first. They took classes in the morning and helped work on renovating the building in the afternoon.

Volunteers used personal vehicles to pick up students and bring them to school, said Steve Sanders, a longtime attorney with the Appalachian Citizens’ Law Center who volunteered at the school that semester.

“The school’s budget was very tight,” Sanders said.

Greene, teachers and volunteers kept the school running even in lean times, however, and Greene spearheaded fundraising for a new building in a secluded hollow. The building, which opened in the mid-1990s, has classrooms, a cafeteria, office space and a half-size basketball court.

Greene received national recognition for his efforts, including an American Hero in Education award from Readers Digest and in 1990 being named the 57th of President George H.W. Bush’s 1,000 Points of Light program, which recognized community service.

Greene’s involvement with the school ultimately ended in 2012 after the Kentucky Attorney General’s Office began investigating concerns of mismanagement.

Contributions had dropped off, and critics questioned some financial decisions, including a deal for Greene to sell his house to the school for $157,000 at a time when it was valued for tax purposes at $78,000, and a payment to Greene of $104,647 in deferred compensation one year when expenses outstripped revenue by more than $300,000.

Greene, who had worked many years for little pay, told the Herald-Leader at the time that he never wrongly took any money from the school, but a judge appointed a new board to oversee the school in 2012, and the members fired Greene.

Prestonsburg attorney Ned Pillersdorf, who now chairs the board, said Greene did “heroic” work at the school that likely saved lives, but he thinks Greene ultimately came to regard it as his “personal fiefdom.”

Greene died in 2018.

‘A lot of good’

Enrollment at the school has reached more than 70 at times, and it has had various programs through the years in addition to the high school, including a preschool, vocational training and adult literacy education.

The school now has 50 students, up from 23 in 2019, and is on track to have 17 graduates in May, Lafferty said.

The school started conducting summer camps for young people and has put on fall festivals for the community as well, raising awareness.

“We’ve rebounded,” Lafferty said of the enrollment. “We’ve got a lot of good going on.”

The school has only high school classes now, along with a wood shop and high tunnels for growing vegetables. Students who want training in trades such as auto mechanics and heating and air conditioning repair attend classes at a public vocational school in addition to classes at the David School.

Katie Stapleton, a freshman, said she benefited from getting more personal instruction after transferring to the David School from another school.

“They pay more attention to what the students need,” she said of the David School staff.

Sophomore Anna Arnett, who is interested in going into nursing, said she wasn’t comfortable at the large public high school she attended before switching to the David School.

“You just felt judged when you walked down the hallway,” she said, but at the David School, “Everybody’s just really close.”

Jaykob Burke, a 17-year-old senior, said there is a greater bond between students — and more respect for each other — at the David School than at the public high school he attended before.

“It feels like a second home here,” said Burke, who would like to study carpentry and start his own contracting business.

The family atmosphere includes a school dog, a mixed-breed stray named Wiley.

When someone stole the school’s tractor a few years ago and then abandoned it nearby, Wiley followed and stayed with it overnight in the rain. The next day, he ran out as Wireman and Lafferty drove by looking for the tractor, helping them spot the machine.

Wireman also has a dog in her room that someone dropped off near the school, now named Maggie. She has a padded enclosure in the classroom but wanders among the students at times.

‘We are scrambling’

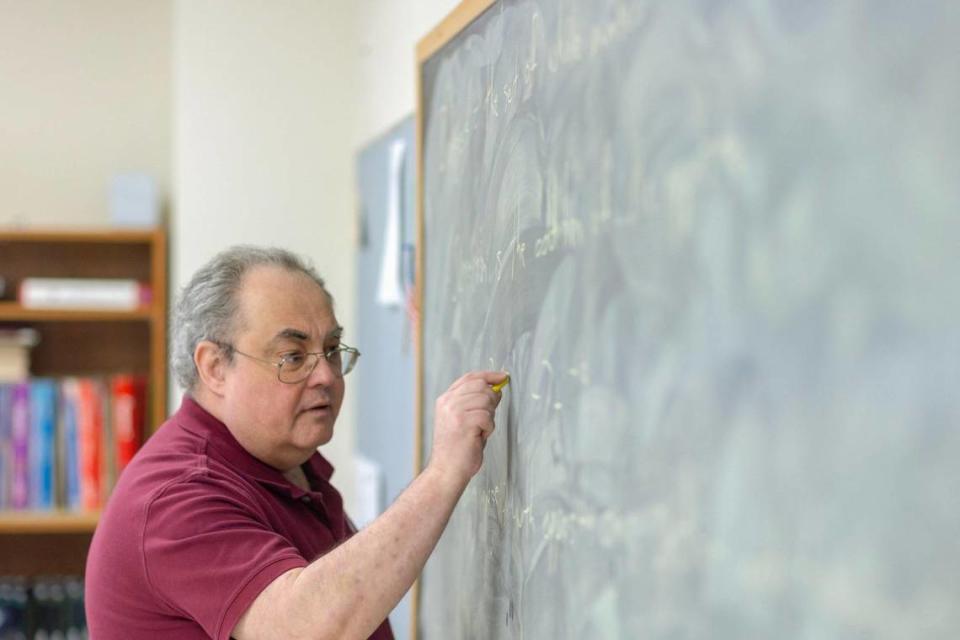

Teachers said some students are behind their grade level when they come to the school, but are as bright as students anyplace else and catch up.

All six graduates last year were college ready and received scholarships, Lafferty said.

“We work together as a team,” Dale Adkins, a former internal medicine physician who teaches biology, physics and chemistry, said of teachers and students.

The school follows Kentucky standards on curriculum, Lafferty said.

The school is considered a private Christian school and opens each day with a prayer, but does not incorporate theology into instruction, and wouldn’t turn away any student because of its Christian underpinning, Lafferty said.

Pillersdorf said the board voted to increase teacher salaries after he took over as chair a few years ago, but the salaries are still relatively low — $20,000 to $22,000 a year.

Teachers see their work as a mission, Wireman said.

“It’s just knowing the lives that you’re changing. That part is very rewarding for us as teachers,” Wireman said.

The school gets some federal money based on the number of students from low-income families, and receives revenue from charitable bingo, but relies on donations for most of its $350,000 annual operating budget.

Raising money is a constant worry. Donations have trended down, Pillersdorf said.

The school is working to apply for grants and broaden the donor base, and is planning a fundraising event, Pillersdorf said.

“We are scrambling,” he said. “I’m determined to keep the school going.”