Kevin Strickland is guilty, Missouri AG says in rebuke of local prosecutor’s arguments

The Missouri Attorney General’s Office has asked a judge to deny a petition seeking to exonerate and free Kevin Strickland, asserting he is guilty in the 1978 triple homicide for which he remains in prison.

Assistant Attorney General Andrew Clarke argued that Strickland, now 62, received a fair trial in 1979 and that he has “worked to evade responsibility” for the Kansas City killings since then.

Monday’s filing means Strickland’s lawyers and the attorney general’s office will likely soon make opposing arguments during an evidentiary hearing before Judge Ryan Horsman, who will decide whether to free Strickland.

More than 60 days ago, Strickland received rare support from Jackson County Prosecutor Jean Peters Baker, who said her office had concluded Strickland, who was 18 when he was arrested, is “factually innocent” in the April 25, 1978, shooting at 6934 S. Benton Ave. The gunfire took the lives of John Walker, 20, Sherrie Black, 22, and Larry Ingram, 21.

Baker’s announcement — with agreement from federal prosecutors, Jackson County’s presiding judge and other officials who say Strickland should be exonerated — came as Strickland’s attorneys filed a petition in the Missouri Supreme Court. The court, however, declined to hear his case. His lawyers then refiled his petition in DeKalb County, where he remains imprisoned.

In responding to the most recent petition, the attorney general’s office argued the Jackson County Prosecutor’s Office has “studiously avoided, overlooked, misinterpreted, or misunderstood much of the evidence in Strickland’s case.”

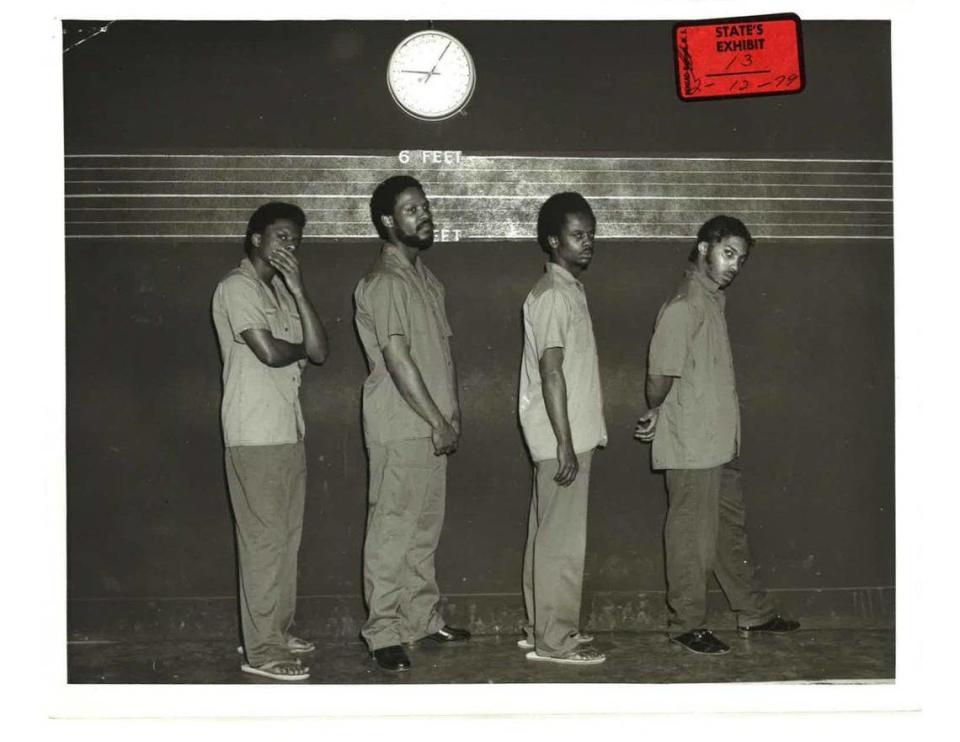

AG’s case against Strickland

The office, under Attorney General Eric Schmitt, contended Strickland is guilty and pointed to police reports in which a witness said Strickland had allegedly offered Cynthia Douglas, the lone eyewitness to the murders, money the day after the killings to keep “her mouth shut.” Clarke, the assistant attorney general, described it as a “tampering campaign” by Strickland.

In the police reports, a friend of Strickland’s, Marcus Harris, said Strickland told him Vincent Bell — who later pleaded guilty in the case — was involved in the crime and that “we” would pay Douglas to stay quiet.

The claim, however, was never mentioned at trial. As part of his review of the case, Jackson County’s chief deputy prosecutor, Dan Nelson, said it was unclear why prosecutors had not asked Harris about it on the stand.

Bell later said Harris thought Strickland was involved in the crime because Strickland was “trying to be big, you know, not knowing what was going on.”

The attorney general’s office also claimed that statements made by Bell and Kilm Adkins — both of whom admitted guilt and swore Strickland was not there — are not new evidence. Even if they were, they are “inherently unreliable” and inconsistent, Clarke wrote.

The two pleaded guilty after Strickland was convicted. In affidavits and interviews with The Star, both said Strickland was not with them during the murders and instead identified two other accomplices who were not arrested.

“I’m telling you the truth today that Kevin Strickland wasn’t there at the house that day,” Bell said as he pleaded guilty in 1979 to three counts of second-degree murder, four months after Strickland was sent to prison. “I’m telling the state and the society out there right now Kevin Strickland wasn’t there at that house.”

Bell testified Strickland was mistaken for a 16-year-old boy named Paul Holiway. Prosecutors now say Holiway is a stronger suspect than Strickland, noting that he was seen with the perpetrators that night shortly before the murders.

After their monthslong review, Jackson County prosecutors concluded that the “core claims” made by Bell at his plea hearing are credible. They said it would have been difficult for Bell, who could not read, to fabricate “an intricate narrative” to write Strickland out.

The attorney general’s office, though, argued that “it is not difficult to believe” that Bell could recall how the shooting unfolded while substituting Strickland with the other teenager.

Schmitt’s office further pointed to statements Strickland allegedly made to detectives. Police claimed Strickland said if he had been with Bell on the “deal” that night, he would have been shooting because, “I love to shoot my gun, I’m a good shot and I love to kill people.” Strickland, the detectives alleged, said if they let him go, they better “draw first” next time or he would kill them.

Jackson County prosecutors have said those statements, which Strickland denied making at trial, did not prove Strickland was at the South Benton home on the night of the killings. They said it could be argued that someone not involved in the crime — who stayed in Kansas City while the others fled to Wichita — would be more likely to make “aggressive statements” to police.

Additionally, the attorney general’s office noted that Strickland had been arrested as a juvenile about two years before the murders on accusations that he shot another teenager in the arm. Strickland was not convicted in the case.

Jackson County prosecutors said they could not figure out how that assault case was resolved. But they noted that the other suspects, “unlike Strickland,” had criminal histories involving armed robbery.

“Strickland has paid a steep price for associating with Bell, Adkins and T.A., for mouthing off to police, and for trying to be cool in helping his older neighbor Bell,” Baker and Nelson wrote in a letter outlining the prosecutor’s office’s review of the case.

The initials T.A. are for Terry Abbott, who was considered a suspect but was not arrested.

In addition to Bell and Adkins, Abbott in 2019 told a Midwest Innocence Project investigator that he knew there “couldn’t be a more innocent person” than Strickland.

One of Strickland’s attorneys, Robert Hoffman, said Strickland’s legal team was disappointed by the attorney general’s response, saying that office overlooked important issues and “misconstrued a number of things.”

The move by the attorney general’s office to oppose Strickland’s petition was in line with its past positions in cases claiming actual innocence. That office has resisted just about every wrongful conviction case to come before it since 2000, according to news outlet Injustice Watch.

“That includes 27 cases in which the office fought to uphold convictions for prisoners who were eventually exonerated,” the Chicago-based news organization reported last year. “In roughly half of those cases, the office continued arguing that the original guilty verdict should stand even after a judge vacated the conviction.”

Did eyewitness recant?

The attorney general’s office and Jackson County prosecutors also disagree over whether Douglas, the eyewitness, recanted her identification of Strickland as the suspect with a shotgun that night. Her testimony was paramount in the case against him.

Decades after the murders, Douglas was working in accounting on a Wednesday in 2009 at the Jackson County Family Court Division when she wrote an email to the Midwest Innocence Project.

Its subject line: “Wrongfully charged.”

“I am seeking info on how to help someone that was wrongfully accused,” Douglas wrote from her county email address. “I was the only eyewitness and things were not clear back then, but now I know more and would like to help this person if I can.”

Baker’s office — which says it wouldn’t charge Strickland today with any crime in the case — has determined Douglas’ email was an “unequivocal recantation.” Because of the email’s circumstances, witness tampering was highly unlikely, prosecutors concluded.

But the attorney general’s office called Douglas’ alleged recantation “remarkably unreliable,” arguing that it does not name Strickland. Because Douglas died in 2015, the office said, the judge can’t know if Douglas sent the email, “let alone absent coercive pressure.”

Douglas also did not sign any affidavits while she was alive, noted Clarke, the assistant attorney general.

“Through his petition, Strickland attempts to make Douglas do in death what she would not do in life: exonerate him,” Clarke wrote.

In previous interviews with The Star, Douglas’ relatives said she tried to walk back her testimony for years and wanted nothing more than to see Strickland freed. They have signed affidavits for Strickland’s attorneys saying the same thing.

“She appeared very disturbed about having made this mistake,” wrote Douglas’ mother, Senoria Douglas. “Cynthia wanted Kevin Strickland out of prison, because she picked the wrong person, and she strongly felt that Kevin Strickland was innocent.”

What’s next?

During a scheduling conference in Strickland’s case Monday at the DeKalb County courthouse in Maysville, the judge set a two-day evidentiary hearing for Aug. 12 and 13.

Lawyers with the attorney general’s office said such a quick time frame could be a burden on the office. Horsman noted that Strickland has been “sitting in prison since before I was born.”

If Strickland is not released by Aug. 28, Jackson County prosecutors hope to file a motion then asking a Jackson County judge to exonerate him. That’s when a bill, which is expected to be signed into law by Missouri Gov. Mike Parson, would allow local prosecutors to seek to free prisoners they have deemed innocent.

Parson could also pardon Strickland, though the governor has said he is not convinced Strickland is innocent.

Now using a wheelchair, Strickland remains imprisoned at the Western Missouri Correctional Center in Cameron.