Here are key players in the trial of John Andrews, who denies encounter with Starkie Swenson

CHILTON - Defendant John Andrews will be tried this week to determine he whether obstructed police in June 2021 by denying he knew the location of Starkie Swenson's remains.

A good deal of the three-day jury trial, though, will focus on the events of August 1983, when Swenson went missing from Neenah, and March 1994, when Andrews was convicted of killing Swenson, even though Swenson's body hadn't been found.

The discovery of Swenson's remains wouldn't occur until September 2021, when, by happenstance, hikers found his tibia in a partially secluded area at High Cliff State Park in Sherwood.

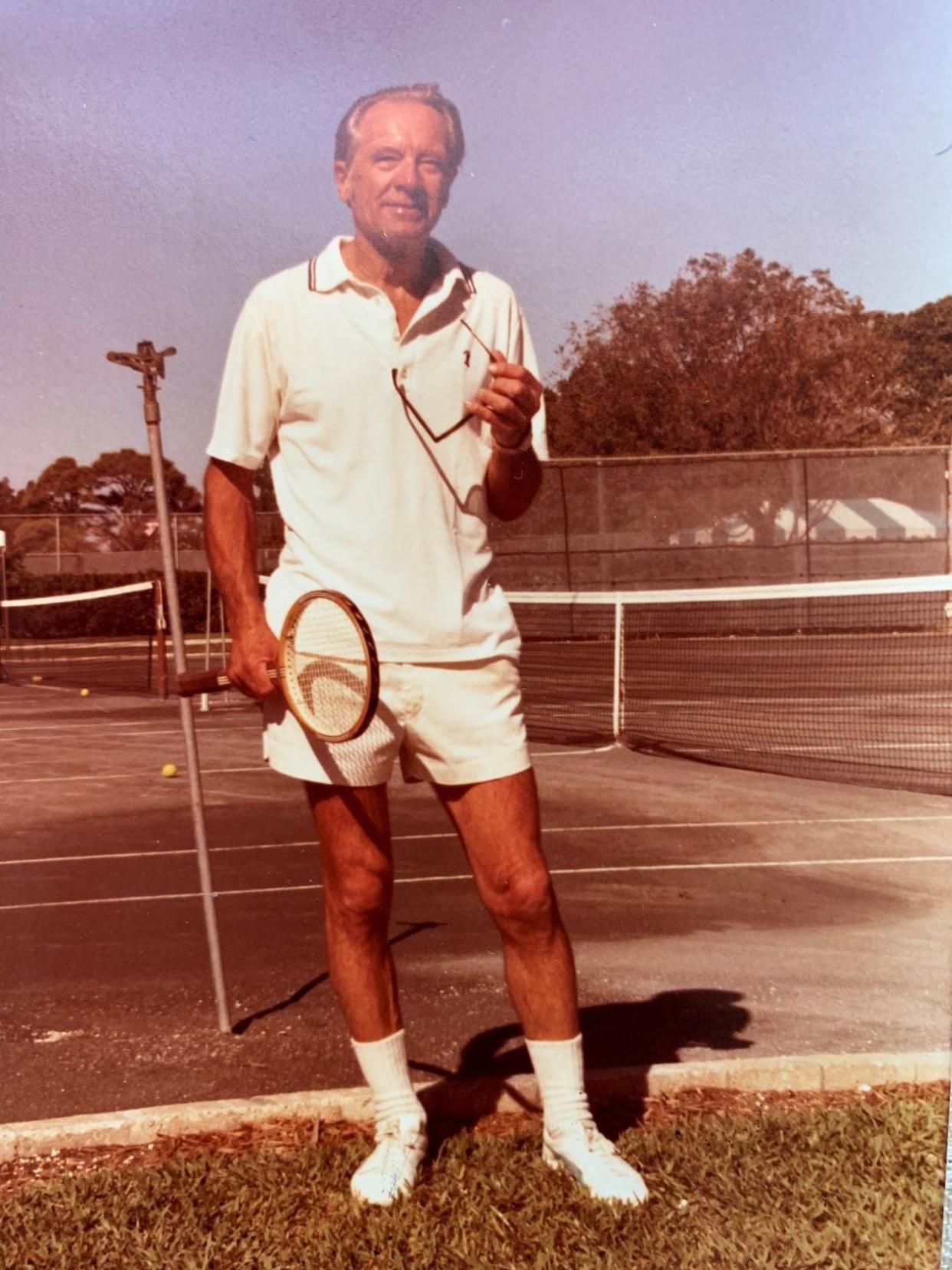

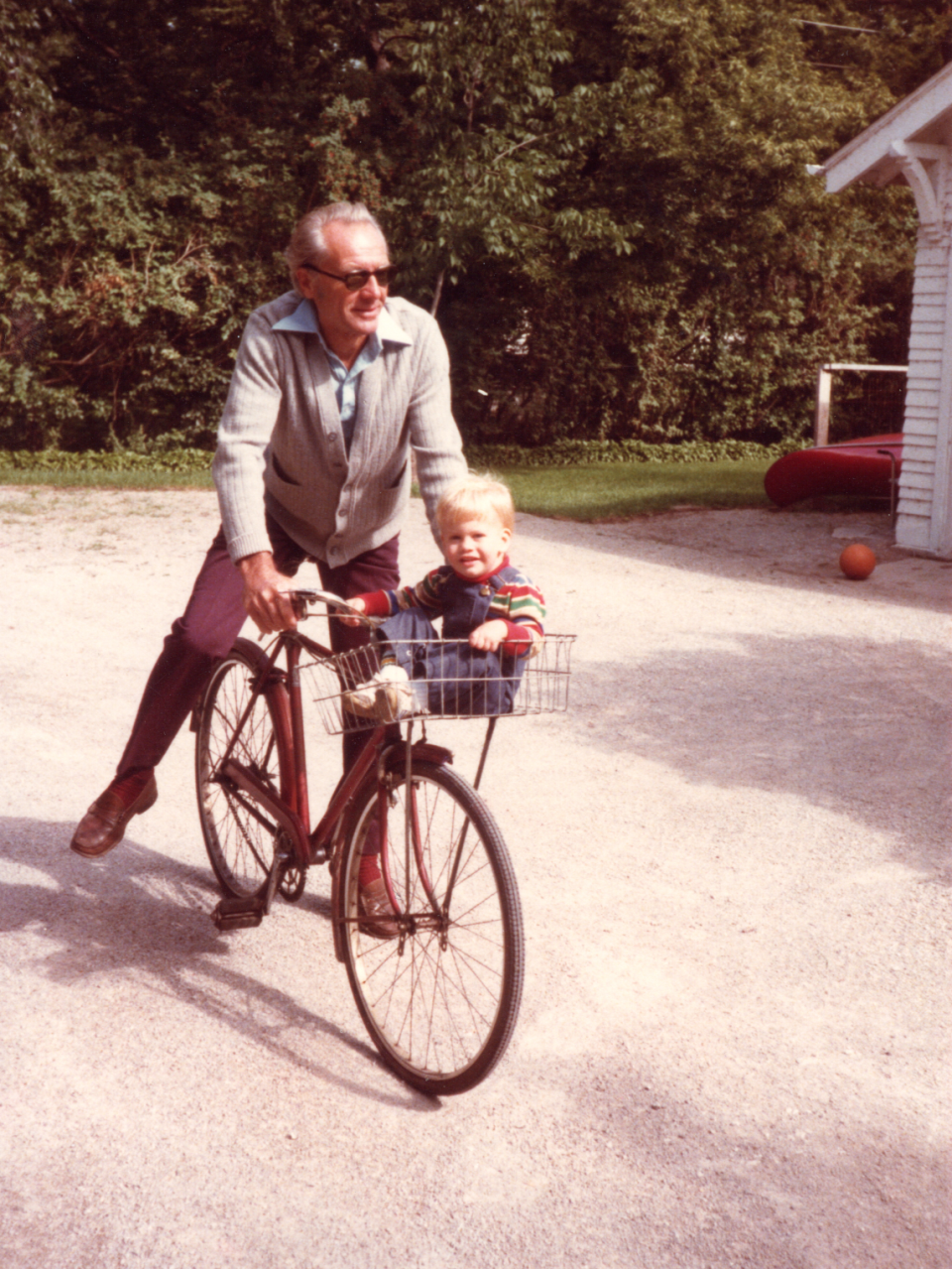

Eric Tillman was a child when Swenson, his grandfather, disappeared. He was a teenager when Andrews was tried for his grandfather's murder. Tillman plans to sit through this week's trial to hear testimony that he otherwise only has read about in police reports and court documents.

"They're going to have to cover a lot of ground," Tillman told The Post-Crescent.

Andrews' attorneys Jonas Bednarek and Catherine White said in a court document that the case "will essentially require a redo of the homicide trial" that occurred in 1994.

Calumet County Circuit Court Judge Carey Reed will preside over the trial on the misdemeanor charge. If convicted, Andrews faces a maximum penalty of nine months in jail and a $10,000 fine. The trial is set to being Wednesday.

Here are five key players in the trial.

Defendant John Andrews

Andrews was 44 when Swenson, 67, disappeared after leaving his Neenah home on a bicycle. Andrews is now 84 and living in Chilton.

Police questioned Andrews in June 2021 about Swenson's whereabouts in an effort to bring closure to the Swenson family. Andrews not only denied any knowledge of Swenson's whereabouts, but he also denied ever seeing or speaking to Swenson in person.

In 1994, Andrews was tried on a charge of first-degree murder for Swenson's death. Police alleged Andrews became enraged over Swenson's extramarital affair with his ex-wife, Claire Andrews, and ran him over with his Pontiac Firebird on the grounds of Shattuck Junior High School in Neenah.

The trial ended after four days when Andrews accepted a negotiated Alford plea and was convicted of a lesser charge of homicide by negligent use of a vehicle. He was sentenced to two years in prison and fined $10,000.

An Alford plea allows for a defendant to be convicted and sentenced while proclaiming innocence. It means the defendant decided it would be better to be sentenced on the lesser charge than take a chance with the jury on the initial charge, which could lead to a longer sentence.

More: Timeline of major events in the death and disappearance of Starkie Swenson

Prosecutor Nathan Haberman

After the discover of Swenson's remains at High Cliff State Park, Calumet County District Attorney Nathan Haberman charged Andrews with hiding a corpse, a felony. The case was dismissed by Reed, who ruled that Andrews' denial of knowing the whereabouts of Swenson's remains when questioned by police didn't constitute hiding a corpse as defined by state law.

Haberman subsequently charged Andrews with obstructing an officer. He intends to call a witness who will contradict Andrews' statement that he never saw or spoke to Swenson in person.

Tillman praised Haberman for his persistence in prosecuting Andrews and seeking justice. He described Haberman as tenacious.

"A crime is a crime, and all crime should be treated that way, even if it appears to be small," Tillman said.

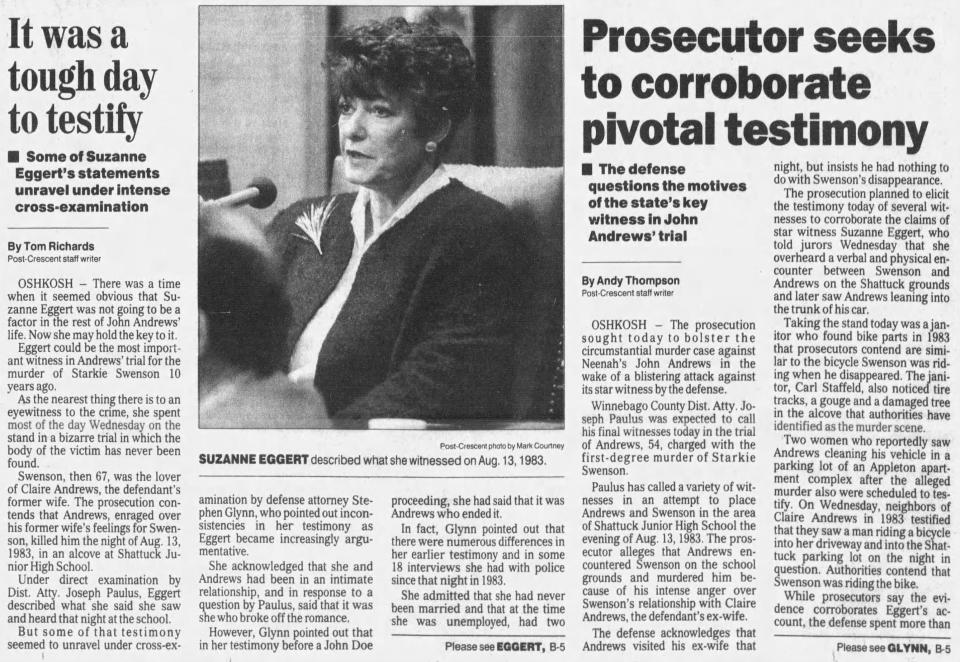

Witness Suzanne Eggert

The prosecution's list of potential witnesses includes Suzanne Eggert, who was the state's star witness in the 1994 homicide trial.

Eggert testified that she overhead a verbal and physical encounter between Swenson and Andrews on Aug. 13, 1983, on the Shattuck property and later saw Andrews leaning into the trunk of his car.

The testimony runs counter to Andrews' 2021 statement that he never saw or spoke to Swenson in person.

At the 1994 trial, Eggert said she didn't tell police the whole truth about what she heard and saw until nearly 10 years later because Andrews threatened to kill her and her two daughters.

Biological anthropologist Jordan Karsten

In September 2021, investigators requested Jordan Karsten, an associate professor of anthropology at the University of Wisconsin-Oshkosh, to respond to High Cliff State Park to analyze, document and remove the recently discovered human remains.

Karsten determined the body, later identified as Swenson, was placed at the site at the time of death or shortly thereafter and that it was intentionally concealed with limestone rocks, according to the criminal complaint.

Rib and pelvic fractures, Karsten deduced, were consistent with Swenson being run over on his bicycle by a vehicle.

Karsten was involved in the case even before the discovery of Swenson's remains.

In April 2021, the Winnebago County Sheriff's Office asked Karsten and his students to conduct a systematic search for Swenson's remains on a property near Omro. The search turned up empty but led police to question Andrews about Swenson's whereabouts.

Attorney Dean Strang

Criminal defense attorney Dean Strang is listed as a potential witness for the defense. Strang and attorney Stephen Glynn defended Andrews in the 1994 trial, and Strang was involved in negotiating the Alford plea.

Defense attorneys Bednarek and White previously filed two motions to dismiss the case – one contending Andrews' 1994 plea prevents further prosecution and one claiming improper prosecution. Reed denied both motions.

Strang gained attention as one of the attorneys for convicted killer Steven Avery in the 2015 Netflix docuseries "Making a Murderer." Avery and his nephew, Brendan Dassey, are serving life sentences for the 2005 murder of photographer Teresa Halbach. They have maintained their innocence, as Andrews has done in the Swenson case.

Contact Duke Behnke at 920-993-7176 or dbehnke@gannett.com. Follow him on Twitter at @DukeBehnke.

SUPPORT LOCAL JOURNALISM: Our subscribers make this coverage possible. Click to see The Post-Crescent's special offers at postcrescent.com/subscribe and download our app on the App Store or Google Play.

This article originally appeared on Appleton Post-Crescent: Get to know the key players in the John Andrews-Starkie Swenson case