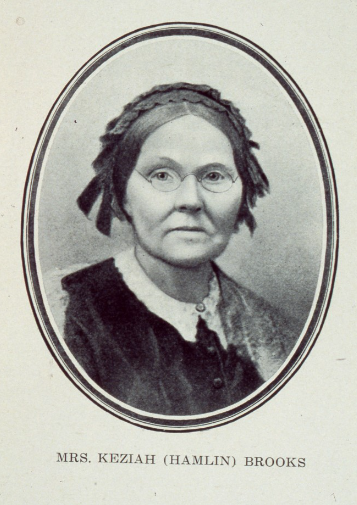

Keziah Hamlin Brooks grew up with Columbus, going from its first white child to innkeeper

The Ohio Country became open to settlers from the newly established United States in the years after the American Revolution. By 1795, Lucas Sullivant had surveyed hundreds of acres in the Virginia Military District west of the Scioto River. Taking his pay for survey work in land, Sullivant laid out a town of his own at the forks of the Scioto and Olentangy Rivers in 1797 and called it Franklinton.

It was a time of hazard and opportunity. The Greenville Treaty Line separating the new settlers from Native America was only a few miles to the north. British forts along the Great Lakes continued their trade with Native Americans.

The new settlers in central Ohio lived in close proximity to friendly natives and hacked their way through dense forests to build homes for themselves. In general, natives and newcomers got along well one with another. But life on the frontier had its moments.

In later years, Henry Howe (a historian who lived from 1816-1893 and wrote the histories of several states, including the HIstorical Collections of Ohio in 1847) told the tale of one of them.

“An interesting anecdote, illustrating the peculiar characteristics of the Indians as the first settlers of Columbus found them, is related of Keziah, the youngest daughter of John and Mary Hamlin.”

The new capital city of Columbus would not be created until 1812. But settlers were here a bit earlier.

“In 1804, Mr. Hamlin built [a] cabin east of the Scioto River, on the spot where the Hoster Brewery now stands [at Livingston Avenue and Front Street], and here, October 16, 1804, his daughter Keziah, the first white child in Columbus was born.”

“At this time a tribe of Wyandot Indians were located near a bend in the river just below the present Harrisburgh bridge. They were very friendly to the Hamlins, and were especially fond of Mrs. Hamlin’s freshly baked bread. On bread-baking days, they would come to the cabin, and lifting aside the curtain which served as a door, enter and help themselves to the contents of the larder without asking permission or saying a word to the occupants. Upon leaving they would throw a hunk of venison or whatever game they had upon the floor in compensation, and then silently take their departure.”

“One day when Mrs. Hamlin was attending to her household duties with nobody present save her infant daughter, who was calmly sleeping in her crib, several of the Indians entered the cabin without saying a word deliberately took up the sleeping infant and carried her away with them to their village, leaving Mrs. Hamlin trembling with fear and anxiety for the safety of her child.”

“As the hours passed by and the child was not returned, she suffered the greatest mental anguish and suspense, until, toward the close of the day, her sufferings were relieved by the return of the Indians bringing with them the child, which wore a beautiful pair of beaded moccasins upon her little feet, and which the Indians had been industriously working upon all day, and had felt the necessity of having the child with them so as to insure a perfect fit. This token of appreciation ... for the kindness and hospitality shown them by early pioneers was preserved, until a few years ago, when the scion of a younger generation of the same house, unfortunately destroyed them when too young to appreciate their value.”

Keziah Hamlin grew up with Columbus and went on to have further adventures of her own. When Keziah was 8, the Ohio General Assembly created Columbus to be the new capital city. When she was 12, the first meeting of the state legislature was held in a modest brick Statehouse on Statehouse Square.

In 1822, at the age of 18, she met a recent arrival from Princeton, Massachusetts, named David Brooks. The two were later married and they began a new life in the emerging Borough of Columbus.

Brooks involved himself in a number of entrepreneurial adventures until he settled with his wife as the manager of the White Horse Tavern. The White Horse was located on the east side of High Street between State and Town streets. A later local history described the tavern in some detail.

“Its name was emblematically represented on its sign by the picture of a white horse led by a hostler dressed in green. It was a one-and-a half-story frame in front, with a long narrow annex to the rear, supplemented by a commodious barn, which occupied the entire rear portion of the grounds. An upstairs veranda, with which the rooms on that floor communicated, opened upon the ample dooryard and furnished a pleasant lounging place in summer. The dining room was ranged with long tables, and warmed from a great open fireplace, out of which, in winter time, the burning logs snapped their sparks cheerily while the guests gossiped around it, seated upon sturdy oak armchairs. In December, 1829, David Brooks became its landlord and made it one of the favorite hostelries of the Borough.”

In later years, the inn became known as the Eagle Hotel, and Brooks was its manager until his death in 1848, leaving Keziah with three sons and two daughters, all of whom worked to support her and the family.

Keziah Hamlin Brooks died in 1875, and is buried in Green Lawn Cemetery with her husband in the Brooks family plot.

This article originally appeared on The Columbus Dispatch: Keziah Hamlin Brooks grew up with Columbus, becoming a local innkeeper