Your kid might not return to a classroom this year. Are teachers unions to blame?

This was supposed to be the semester when America's largest school districts reopened.

COVID-19 vaccinations are rolling out. Studies have shown in-school transmission of the virus is low. Thousands of schools have successfully brought kids back in person, while kids who stayed home have struggled.

Yet many parents are realizing their children may never see their teachers in person this year. A growing number blame their local teachers union, even as President Joe Biden and his administration make in-person instruction a priority.

"It's so frustrating," said Adam Grandi, a father of two elementary students in San Francisco, where the district scrapped a Jan. 25 reopening date because the school board couldn't reach an agreement with the union. "Of course, we all feel for the teachers, and we appreciate the work they're doing, but it feels like the union is looking out for themselves, which is their job, but it’s at the expense of a whole lot of kids and families."

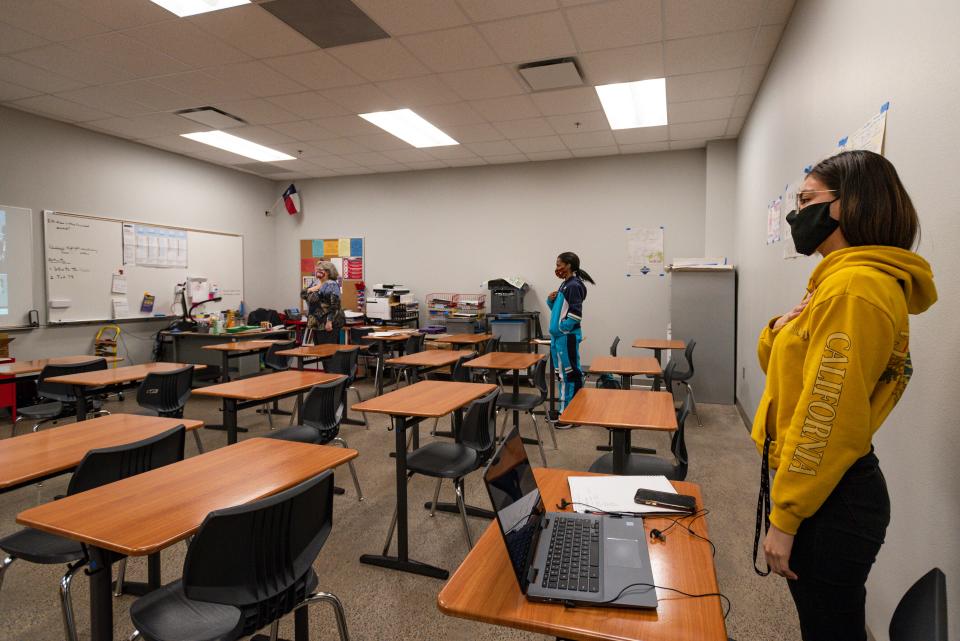

Almost three out of four urban districts offer only online instruction, according to a new report from the Center on Reinventing Education at the University of Washington. Some districts that got kids back to schools face major pushback from unions, predominantly around safety measures and the spike in COVID-19 infection rates in the community.

In Chicago Public Schools, the nation's third-largest district, the teachers union voted to continue to work from home rather than report to school buildings Monday – a move that effectively defied the city's reopening plan after a slim majority of union members approved the resolution over the weekend.

"Our members took a vote to keep learning remotely to avoid disaster," Stacy Davis Gates, vice president of the Chicago Teachers Union, said last week.

Chicago's district leaders announced they would start vaccinating teachers in mid-February, giving priority to those working in buildings and older workers. The union wants the district to delay in-person learning until all teachers are vaccinated.

More than 100 Chicago teachers and supporters held a march on the South Side today in the CTU's ongoing push for a safe reopening plan: “This is about saving our lives." https://t.co/vCEO959OCK

— Chicago Sun-Times (@Suntimes) January 18, 2021

Biden directed the Departments of Education and Health and Human Services last week to provide clear guidance and resources to reopen schools and child care centers while enacting more stringent worker safety standards.

First briefing: Biden emphasizes science in national plan to tackle COVID-19

Even before he took office, Biden's team proposed an additional $130 billion in federal money for schools that could be used to reduce class sizes, improve building ventilation, pay for protective gear and ensure nurses are available – things many unions demanded. It's unclear whether Congress would approve such a sum or do it in time to affect the spring semester.

"The honest answer is none of us know how this is going to play out," said Mike Petrilli, president of the Thomas B. Fordham Institute, a conservative think tank based in Washington that follows education issues.

Some reopen without union

Absent the money, time or consensus to give teachers what they want, some schools are forging ahead with reopening anyway.

Leaders of Baltimore City Public Schools announced a plan to open classrooms for the youngest children Feb. 16, followed by older elementary students as well as ninth and 12th graders March 1.

Baltimore schools CEO Sonja Santelises said more than half of third through 12th graders have failed a class during remote learning, and the district can't wait for all teachers to be vaccinated before opening buildings.

The Baltimore Teachers Union protested that move, saying it wants the district to provide a COVID-19 testing plan, a nursing plan and new ventilation assessments for all classrooms.

Teachers shouldn't be vilified for asking for those basic items, said Diamonté Brown, the union president.

"All this rhetoric about the union stopping this or that – we're not stopping anything," Brown said. "We don't get to negotiate if we go back, but how. Ultimately, some teachers will come in, some won’t and some will retire."

New York City's mayor and teachers union battled over reopening schools. Young students and those with disabilities were given the option to return to classrooms last month, but as virus rates crept up again in January, the union raised concerns about safety.

Determined to keep schools open, New York City Mayor Bill De Blasio said the availability of vaccines will help teachers and students return to class. Fewer than 350,000 of the 800,000 vaccine doses delivered to New York City have been administered, the United Federation of Teachers reported in a story last week.

The politics of reopening

The simmering tension around schools staying closed comes at a complicated time: Parents are frustrated with remote learning, but infection rates in many communities are climbing.

In districts where classrooms are open, many families keep their kids home. In Florida, the Miami-Dade school system offers in-person instruction every day. Forty percent of students have taken advantage of the option, according to the teachers union.

Studies have shown schools that reopened with mitigation tactics have not contributed to major outbreaks in places with mild to moderate community transmission. The research is less conclusive about the safety of reopening in places with higher rates of infections. A new study by researchers in Florida and China shows that although children are less likely to get sick, they are 60% more likely than adults over 60 to spread the infection.

That's why some doctors are recommending schools stay closed, including Vin Gupta, an intensive care unit doctor acting as a medical consultant for the Chicago Teachers Union. Others from Chicago, the San Francisco Bay Area and Ann Arbor, Michigan, urged schools to reopen.

Some have argued that because schools don't contribute significantly to community spread, they should stay open.

I disagree. There is explosive #covid19 spread. Most schools should be closed through the winter.

My @washingtonpost op-ed: (1/6) https://t.co/NDh0wz2VtR— Leana Wen, M.D. (@DrLeanaWen) November 24, 2020

Marc Lipsitch, professor of epidemiology at Harvard University and director of the Center for Communicable Disease Dynamics, said the thinking has shifted toward reopening schools because data shows younger grades are not typically the main source of transmission, at least when control measures are in place.

“The balance has changed, and there’s a sort of mantra now that schools should be the last to close and the first to open,” Lipsitch said at a Harvard event in mid-January.

In the absence of strong national guidance, districts have acted as their own epidemiologists along with local and state health departments, said Robin Lake, director of the Center on Reinventing Public Education, which surveyed districts' reopening plans.

Politics take hold at the local level, and unions are a powerful part of that structure, she said.

"Biden's push to get most schools reopened in the first 100 days means he's going to have to step into the politics of this," Lake said.

A San Francisco showdown

Teachers union officials maintain that the health and safety of their members and the community are paramount.

Susan Solomon, president of the San Francisco Teachers Union, said rates of transmission are too high to reopen and the district has not committed to enough testing for staff and students.

"Staff are doing all we can to provide instruction and social/emotional supports to our students and their families, and we want very much to return to in-person instruction with our students when it is safe," she said in a statement.

District officials said the union is making new requests, such as holding off on returning until rates of virus transmission drop below what the school board and state and local health orders are willing to allow.

The stalled negotiations have drawn ire from parents who want their children back in classrooms.

Grandi, the father in San Francisco, works for the city's health department as a deputy director of a child mental health clinic. He frequently sees children who are struggling or not engaged in remote learning because they don't have stable resources or their families don't have the bandwidth to help them.

Those children would be better served by attending school in person, and their needs are getting overlooked, Grandi said.

Andrew Reeder, a San Francisco parent with a 9-year-old daughter, said it's frustrating to see other cities with higher rates of virus transmission send kids back to school.

"I think at this point they should just say, we’re not going back," he said. "It feels like there's no recourse for us as parents."

Teachers who wish to return to classrooms said the union isn't representing their views.

David Moisl teaches kindergarten in San Francisco and has a child in first grade. He learned through media reports that his union doesn't believe moving teachers to the front of the vaccine line is, on its own, enough to reopen schools.

"I was under the impression that's what would end this pandemic," Moisl said. "It feels like the light at the end of the tunnel has been extinguished."

Parents aren't on the same page

Parent groups united around reopening schools have popped up in lots of large districts. Many are led by more affluent, white parents who may not represent the views of the parents who make up the majority of an urban district's population.

In places where in-person learning is an option, white parents have been far more likely than Black and Latino parents to return their children to classrooms, according to a survey by Ipsos Public Affairs.

"It’s very difficult for parents to organize around a single voice based on what they want districts to do," said Bradley Marianno, a professor at the University of Nevada-Las Vegas, who studies teachers unions. "There’s a whole host of factors at play that makes it easier for teachers to be heard over parents."

If schools haven't started planning for on-premise instruction, and if they don't have the cooperation of their labor partners, it's probably too late to expect classrooms to reopen this year, Marianno said.

In the short term, Biden's team will be challenged to nudge schools open, said Alastair Fitzpayne, a senior fellow at the Aspen Institute, a nonprofit organization that studies policy and education in Washington.

The new administration has a head start with the $900 billion relief package passed in December that includes money for schools, Fitzpayne said, but any new package would take time to develop and implement.

"To have an impact on this semester," he said, "you’d want the additional money and the guidance to get to schools now."

Contact Erin Richards at (414) 207-3145 or erin.richards@usatoday.com. Follow her on Twitter at @emrichards.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Biden wants to reopen schools, but teachers unions resist