Kids develop views on race when they're young. Here's how some preschools are responding.

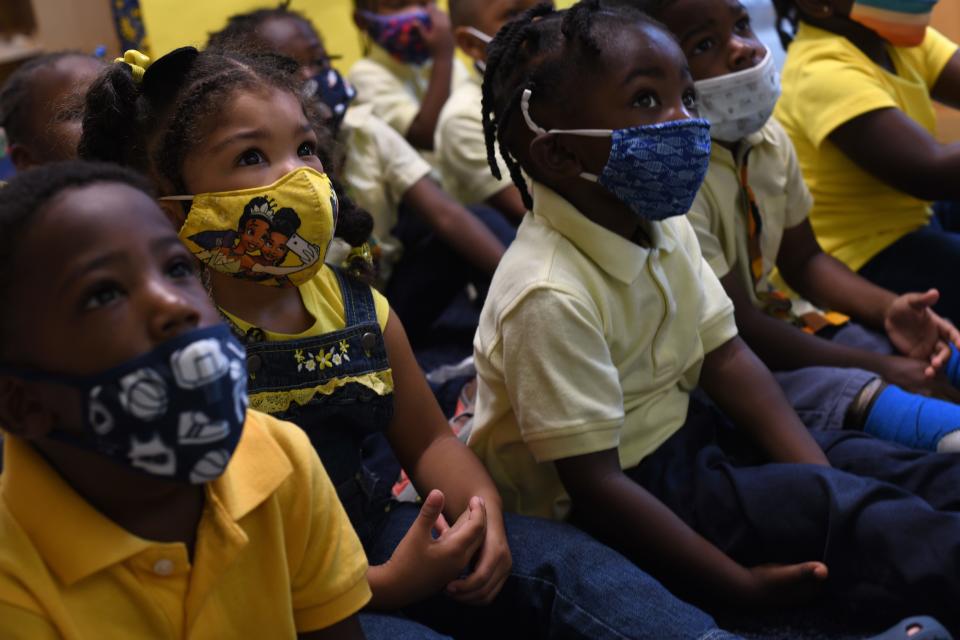

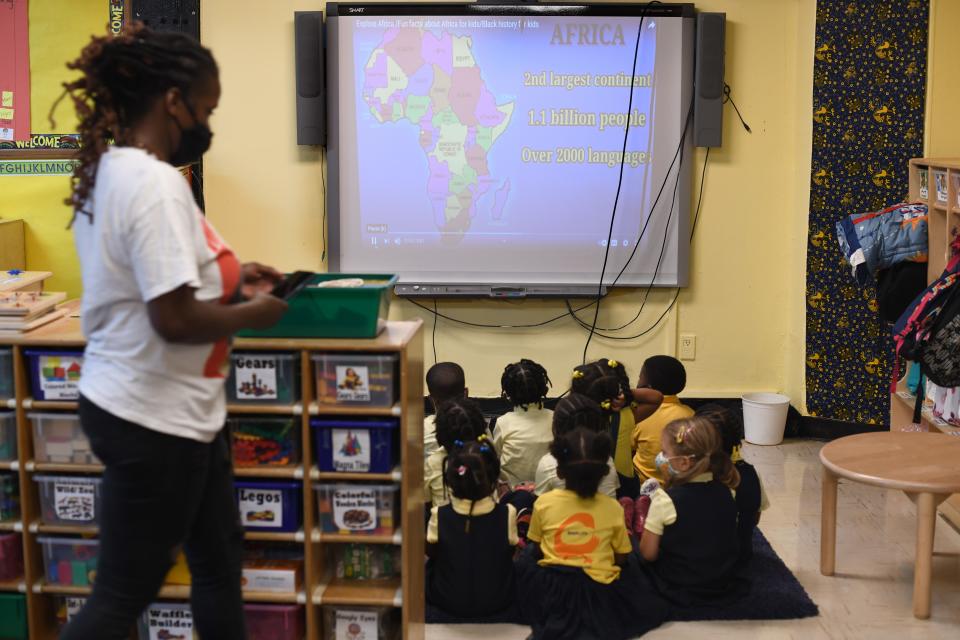

On one of their first days back to school, a group of 3-year-olds at Little Sun People preschool in Brooklyn, New York, spent the morning learning how to write their names. On sheets of construction paper, they filled in the letters with brightly colored squares of cloth from Kenya, Nigeria and other countries across the African continent.

Next door, their 4-year-old classmates learned about body parts. “Who likes their hair?” teacher Aaliyah Barclift asked the students. Arms shot up. “Who likes their skin? Their beautiful skin?” Arms shot up again. “Yours is like chocolate,” she told one student. “Mine is like a caramel sundae.”

After reading aloud a picture book whose Black protagonist describes all the qualities she loves about herself, Barclift’s students proceeded to make self-portraits. On pieces of round, brown paper, the children drew their eyes and noses and mouths; they completed their looks with strands of textured hair, selected from a pile of extensions Barclift had procured for the class.

Ninety-eight percent of Little Sun People’s students are Black, as are all its teachers. Amid the increasing debate over critical race theory, Little Sun People is teaching kids about race in preschool – when many parents, as well as experts, say such conversations should start.

Over the past few months, schools have come under scrutiny over how they teach students about race and racism. A recent USA TODAY/Ipsos poll found most parents believe children should learn about the ongoing effects of slavery and racism in U.S. society, but slightly less than half support the teaching of critical race theory – a once-obscure legal framework that examines the same concepts.

Critical race theory, DEI and more: What do those terms really mean?

Largely lost from the debate, however, is a discussion about the age at which children should begin learning about racial identity and all its complexities – and about how to introduce those concepts in an appropriate, intentional way. In that same USA TODAY/Ipsos poll, parents were most likely to say children should start learning about racism in kindergarten – the youngest age group they could select.

Children will be exposed to racism regardless of whether they learn about it in the classroom, experts say. Which is one reason Little Sun People – which uses an Afrocentric curriculum – tries to affirm its predominantly Black students’ identities with every lesson.

When it does exist, culturally grounded education tends to focus on older students. Many educators assume preschoolers are too young to understand and think about identity, too innocent to learn about the challenges that come with diversity. But experts say children, who begin forming racial attitudes in infancy, should begin learning about those topics as early as possible.

In preschool, “we have this unique, wonderful opportunity to really be open and talk about race in a way that creates acceptance for all people,” said Rosemarie Allen, a professor of early childhood education at the Metropolitan State University of Denver. "If we don’t shape that learning, then (children) draw their own conclusions based on limited information.”

Racial stereotyping starts young – as early as 9 months

At birth, research shows, babies look equally at faces of all races. But they quickly begin to notice physical differences in people, according to Allen, and within a few months, to pay more attention to faces whose race matches that of their caregivers. By nine months they can lose the ability to distinguish between the faces of other races if they’re not exposed to diversity. Absent such exposure, for example, a white baby can distinguish between the faces of her white caregivers but not between those of Black people.

By the time they’re 2 years old, many children demonstrate a strong preference for people of their own race, Allen said, and by 3 they begin to categorize people based on their race. It’s during these early experiences that implicit biases – preconceived, often negative perceptions about people who are different – begin to entrench themselves in children’s minds.

“In order to break that trend, we have to make sure that diversity is well-presented in their lives,” Allen said.

Little Sun People was founded in 1980 by Barclift’s mom, Fela Barclift. A lifelong resident of Brooklyn's Bedford-Stuyvesant neighborhood, the elder Barclift grew up attending what at the time were known as "ghetto schools." Everything in the community was short on funds or investment, she said, including its schools.

Fela Barclift was a smart, driven child, but she felt invisible and terrified; she doesn't remember ever raising her hand. "There was nobody there who was set up to help me or children like me," she said. Most of the teachers at her predominantly Black school were white.

Once Barclift became a parent, she was adamant about setting Aaliyah on a different educational trajectory.

"I was hoping I would find a school that had little brown dolls or pictures of Black or brown people on the wall," she said. "I found not one answer to those little prayers I had."

So, Barclift decided to take matters into her own hands. "I wanted something different for my own children, and for the children in our community," she said.

The way she sees it, culturally relevant teaching has to start early. "You really can't wait until someone's in middle school, high school and college to instill these things," she said. By then, she said, it can be too late for people to see themselves as "powerful, as having agency, as being valuable, being beautiful, being creative, being smart."

Community members seem to agree with that premise. With just 56 seats, Little Sun People has a wait list of more than 400 students. Some of its classes are paid for and enrolled through New York City's Department of Education, which has helped drive the demand.

Fela Barclift was recently selected as a finalist for the David Prize, which awards $200,000 each, no strings attached, to five New Yorkers working to make the city a better place to live. If she wins, she plans on formalizing the Little Sun People curriculum so it can be taught in schools across the metropolis.

The demand for Little Sun People reflects a larger trend in which parents of all races are seeking out programs for kids of all ages that celebrate diversity and self-love. Nationally, culturally responsive education programs, including those espousing Afrocentric values, have grown in popularity in the past decade or so.

Meanwhile, amid widespread recognition of the limitations of existing curricula – and in the aftermath of George Floyd’s murder – teachers are eager to make their lesson plans more inclusive. A study published this year found an uptick in educators’ requests for antiracist classroom materials following recent high-profile incidents of police brutality.

We all have a unique perspective: Sign up for This Is America, a weekly take on the news from reporters from a range of backgrounds and experiences.

Exposure matters, even if you don't go to one of these preschools

Tenika Jackson founded Future Leaders Academy, a preschool program in Los Angeles, partly in response to the bullying and teasing so many nonwhite students face by the time they’re in elementary school. A clinical psychologist, Jackson wanted to create an early learning community where children learn to appreciate diversity.

She couldn’t find any early learning programs in her area that make social justice a key component of their curriculum, so she, like Fela Barclift, took matters into her own hands. Future Leaders Academy officially opened its doors last year.

At the preschool, students celebrate different cultural holidays and figures; they engage in dramatic play and, like their peers at Little Sun People, do art activities that help them understand their own identities and how they intersect with those around them.

“As they get older they’ll have an appreciation for people who are from different cultures … versus thinking that everything that’s different is bad,” Jackson said.

Because implicit biases develop so early in life, experts and advocates say it’s critical that children gain this kind of exposure to diversity at a young age.

In areas without lots of diversity, educators and parents can turn to media such as books, art and cartoons, said Lisa Wilson, the director of equity and outreach at Zero to Three, an early learning advocacy organization. The goal, experts agree, isn’t to encourage color-blindness but rather to offset those biases by celebrating diversity. It’s also to empower children of color who, at least historically, have seldom seen themselves represented in the media they consume.

Looking for books about racism? Experts suggest these must-read titles for adults and kids

In Little Sun People's early days, learning materials featuring people of color were all but nonexistent. Fela Barclift and her team gathered books about animals and, once that avenue was exhausted, began editing books with white characters. They colored in the characters' faces and curled up their hair to make them look like the students Little Sun People served.

"We had to literally create everything because nothing was available at that time," she said. Barclift also brought in community artists to paint the walls, the murals featuring Black heroes and scenes from Africa, and recruited parents to make dolls.

These days, “everything we teach, we try to make sure there’s some kind of relationship or connection to that child’s culture, family, people, history,” Barclift said. For a math lesson at Little Sun People, children might learn about the Egyptian pyramids; in cooking class, they might replicate the dishes of their African ancestors.

Isaiah Frazier, a 33-year-old father of two current and former Little Sun People students and a lifelong Brooklyn resident, says his children have benefited from the program in both obvious and less obvious ways. Yes, they’ve received a quality education from well-trained teachers, but they’ve also developed “a sense of becoming,” as Frazier puts it – an intuitive, inherent confidence about their assets as Black people.

‘Students are going to be having these conversations with or without us’

Adults often feel wary of talking about racial differences and injustice, especially with young children. But “students are going to be having these conversations with or without us,” said Jenny Muñiz, a policy analyst at the Washington, D.C.-based think tank New America.

Muñiz used to be a second grade teacher in a predominantly immigrant community in Texas. In 2016, amid larger debates about immigration enforcement, one of her students asked Muñiz if she thought darker-skinned people would be deported.

“It revealed to me that kids are picking up these messages,” Muñiz said, describing children as sponges. “They’re picking up on community fears, taking this question into the classroom and connecting it to skin color.”

Using storytelling, media and toys, educators can teach young children about racial justice – and injustice – by focusing on themes they’re already learning as part of their social-emotional development: fairness, empathy and respect. They can talk about police, for example, as people who are meant to practice those values and keep their communities safe.

After Floyd’s murder last year, many parents approached Little Sun People seeking guidance on how to discuss the event and related protests with their children. Fela Barclift advised them to wait for their kids to ask questions. Those questions can help educators and parents better gauge how, if at all, children are processing traumatic news events.

George Floyd. Ahmaud Arbery. Breonna Taylor: What do we tell our children?

More advice: How parents can talk to their children about racism

In some cases, what’s happening – or what happened – in the world is simply too heavy to talk about with young children. A few years ago, on Martin Luther King Jr.’s birthday, some of Little Sun People’s students watched a video about King’s life; the movie showed King being shot. One of the students couldn’t sleep after seeing the clip, crying incessantly after viewing King’s murder. The incident was a lesson in how to best expose young children to the realities of racism – now, Little Sun People talks about King’s life and death, but doesn’t show children that scene.

“I really don’t favor giving our children the harshest end of things,” Fela Barclift said. “They’re going to have so much opportunity to find this harshness – the hard, bad, difficult challenging stuff. It’s going to be there – it’s waiting for us – because it’s always there.”

The goal isn’t for children to internalize the injustices suffered by their predecessors, to feel like it’s them against the rest of society. Quite the opposite. As one Little Sun People parent, Kara Benton Smith, put it, “We want them to learn not just the struggle but the triumphs, too.”

One of Benton Smith’s children, a Little Sun People alumna who’s now 12, has been “talking about slavery for a long time.” And the way she was introduced to the topic was through dramatic play – specifically, a story about Harriet Tubman. At 2 years old, Benton Smith’s daughter learned many enslaved people, like Tubman, were also heroes.

“The reason we’re doing this is to give a sense of empowerment, a sense of possibility,” Fela Barclift said. “We want them to be able to contribute on a huge level … by being able to see themselves as the incredible treasures they are, to see that the possibilities are unlimited.”

Contact Alia Wong at (202) 507-2256 or awong@usatoday.com. Follow her on Twitter at @aliaemily.

Early childhood education coverage at USA TODAY is made possible in part by a grant from Save the Children. Save the Children does not provide editorial input.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Race education in preschool? How some daycares teach kids about racism