Kids Just Brought Montana To Court Over Climate Change. The Case Could Make Waves Beyond The State

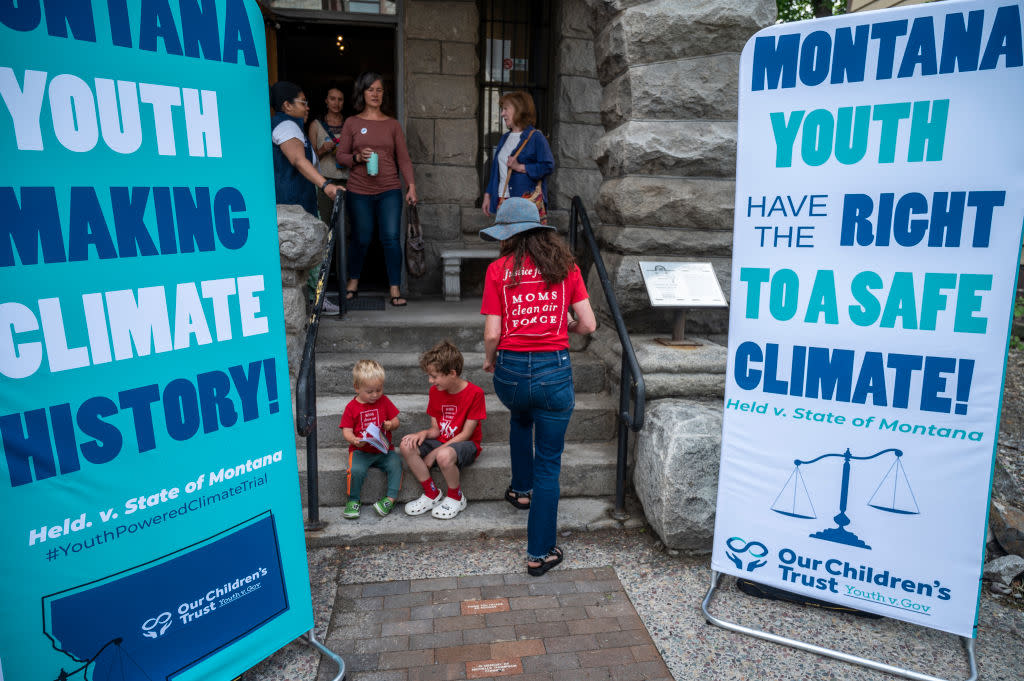

Supporters gather at a theater next to the court house to watch the court proceedings for the nation's first youth climate change trial at Montana's First Judicial District Court on June 12, 2023 in Helena, Montana. Credit - William Campbell—Getty Images

Kian T. did not have to give his full name in open court. The judge and the attorneys knew it, but the spectators and press crowding into the courtroom in Helena, Mont., on June 14 didn’t. Kian T. is only 18 years old and, as a minor, he is afforded a certain amount of anonymity. Still, full name or not, he had a personal story to tell about what has become of the climate in his state.

“I have had many, many soccer practices canceled for smoke and heat,” he said. “Playing soccer on turf in the heat is miserable. Imagine your feet are boiling in your cleats, burning every single step you take on the field. It burns you out.”

Claire V., 20, followed Kian T., and for her it is the local wildfires that have made living in Montana so hard. “When I think about summer, I think about smoke,” she said. “It sounds like a dystopian movie, but it’s real life.” As for the prospect of a smoke-free summer in Montana? “Unimaginable,” she said.

Kian and Claire are just two of 16 plaintiffs—ages five to 22—in the case of Held v. State of Montana, a first of its kind trial in which the youths sued the state, arguing that the government was violating their right to a clean and healthy environment, and that their generation will bear a greater burden from climate change than the adults doing the damage. The case, which was heard from June 12 to June 19, was a bench trial, meaning that there was no jury present; Judge Kathy Seeley alone will render a decision, which the attorneys expect to be forthcoming within 60 days.

Even before the ruling comes down, however, the suit is teeing up other, similar cases both here and around the world. Our Children’s Trust, the advocacy group that brought the suit on behalf of the plaintiffs, has similar cases on behalf of children pending in Utah, Virginia, Hawaii, and Alaska. They also have a case at the federal level: Juliana v. United States. On top of this, the group is consulting in a dozen similar cases overseas, including ones in Australia, New Zealand, Colombia, Uganda, and Pakistan. A positive ruling by Judge Seeley could serve as a powerful legal precedent.

The plaintiffs in the Montana take particular issue with a key portion of the Montana Environmental Policy Act, passed in 2011, which affirmatively forbids officials in the state’s Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ) from considering greenhouse gas emissions or other climate impacts when permitting such projects as coal-mining or power plant construction. In May, the state’s Republican Gov. Greg Gianforte signed a bill that tightens that prohibition further.

“Some people had said that the language in the [original] law was vague and the state actually could consider climate change,” says Julia Olson, chief legal counsel for Our Children’s Trust. “So in this legislative session, the legislature made the language stronger, so it’s really clear.”

The plaintiffs argue that not only are those laws misguided, they’re flat-out unconstitutional—and on its face, they’re right. In 1972, a state constitutional convention passed a constitutional amendment mandating that, “The state and each person shall maintain and improve a clean and healthful environment in Montana for present and future generations. The legislature shall provide for the administration and enforcement of this duty.” It’s the constitutional question Seeley is being asked to rule upon and if she decides in the plaintiffs’ favor, the 2011 and 2023 laws will fall away.

“We are at a decision point about taking action on climate change,” testified plaintiffs’ witness Peter Erickson, a climate change policy researcher at the Stockholm Environment Institute in Seattle, Wash., on the fourth day of the trial. “The world community has decided that we must.”

Their Day in Court

Publicly, the state has come out swinging against the case. The lawsuit, said Emily Flower, spokeswoman for Montana Attorney General Austin Knudsen, in an email to TIME, is “a publicity stunt staged by an out-of-state organization that has exploited well-intentioned children and forced Montana taxpayers to foot the bill. In reality, this case is a challenge to a discrete provision of a procedural state statute that has only been in existence in its current form for less than a month and a half and has no impact on greenhouse gas emissions.”

During opening arguments, Assistant Attorney General Michael Russell echoed the idea that the case would not have any real effect on the state’s contribution to climate change. “Montana’s emissions are simply too minuscule to make any difference,” he said. “Climate change is a global issue that effectively relegates Montana’s role to that of a spectator.

Maybe. But Montana and neighboring Wyoming are home to the Powder River Basin, the largest coal deposit in the U.S., which is responsible for more than 40% of American coal production. That coal may not all be burned in Montana, but it has its origins there. “The climate crisis that we are experiencing is being substantially contributed to by Montana,” says Olson. If the plaintiffs win the current suit, the Montana DEQ would have to scrutinize future permitting at the basin, perhaps limiting the amount of extraction that takes place there.

Adds Roger Sullivan, lead Montana counsel for Our Children’s Trust, who presented the case for the plaintiffs: “The argument you’ve heard from the state is, ‘So what? What difference does Montana make?’ But as a matter of scientific fact it does make a difference.”

The trial was scheduled to run for two business weeks, with the plaintiffs going first, and they put their five days to good use. Additional youth plaintiffs testified, including Mika K. and Olivia V., both of whom have asthma, which they said had been exacerbated by Montana’s increasing incidence of wildfires. “It feels like it’s suffocating me, like if I’m outside for minutes,” Olivia said. “Climate change is wreaking so much havoc on our world right now, and I know it will only be getting worse.”

Pediatrician Dr. Lori Byron testified, arguing that wildfires, smoke conditions, and extreme temperatures can damage the lungs and brains of children, which are still developing, more than they can those of adults. She also described the emotional impact of experiencing such extreme conditions, testifying that they amount to adverse childhood experiences. According to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, such experiences can have lifetime impact, including increasing the risk of being both a perpetrator and a victim of domestic violence, she noted. In addition, she said, “Wildfires, for example, instill fear that you will have to leave your home, as well as the smoke that creates a pall over your life and makes one unable to do the things you enjoy.”

Other plaintiffs’ witnesses included Cathy Whitlock, an earth scientist and professor at Montana State University, who explained that Montana has suffered from rising temperatures more than most other states due to its high elevation; and Steven Running, professor emeritus of ecosystem and conservation sciences at the University of Montana and a co-winner of the 2007 Nobel Peace Prize for his work on the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. “As the summertime gets longer,” Running said, “this is when our growing-season droughts get worse and the final thing is when wildfires get more wild than we’ve ever seen.”

As Sullivan told TIME, reflecting on how the trial went: “We were able to put into evidence all of the proof of our allegations that we feel are needed to get the relief that we have requested.”

For the Defense

The same could not be said of Montana’s case. While the plaintiffs used all five of their allotted days to present their evidence, the state used only a single day and called only three witnesses. Two were employees of the Department of Environmental Quality, who acknowledged that under state law they did not have the authority to deny permits for work that results in the release of greenhouse gasses.

The final witness was Terry Anderson, an economist and fellow at the Hoover Institution who testified for only 15 minutes, using that brief time partly to make the point that Montana was responsible for only 0.08% of the world’s greenhouse gas emissions. When asked on cross-examination where he had gotten that figure, he responded that he couldn’t say with certainty but that it was from a “reliable website.” The plaintiffs moved to strike the testimony; Judge Seeley denied the motion but told the plaintiffs’ attorneys, “You’ve definitely raised some questions about how he got the numbers.”

For reasons the state did not explain, it canceled the appearance of climatologist Judith Curry, professor emerita at the Georgia Institute of Technology who has spread doubt about global warming. Curry was the sole scientist Montana had on its witness list. The trial thus ended on day six, rather than the planned day 10, and the decision now rests with Judge Seeley. There is no way of knowing how she’ll rule—and no way of knowing the effect that ruling will have on the similar pending cases. The 16 young plaintiffs, however, are of one mind on what their larger goal—and their larger fear—is.

“It is really scary seeing what you love disappear before your eyes,” said Sariel, a plaintiff and a member of the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Native American tribes. “This case is important.”