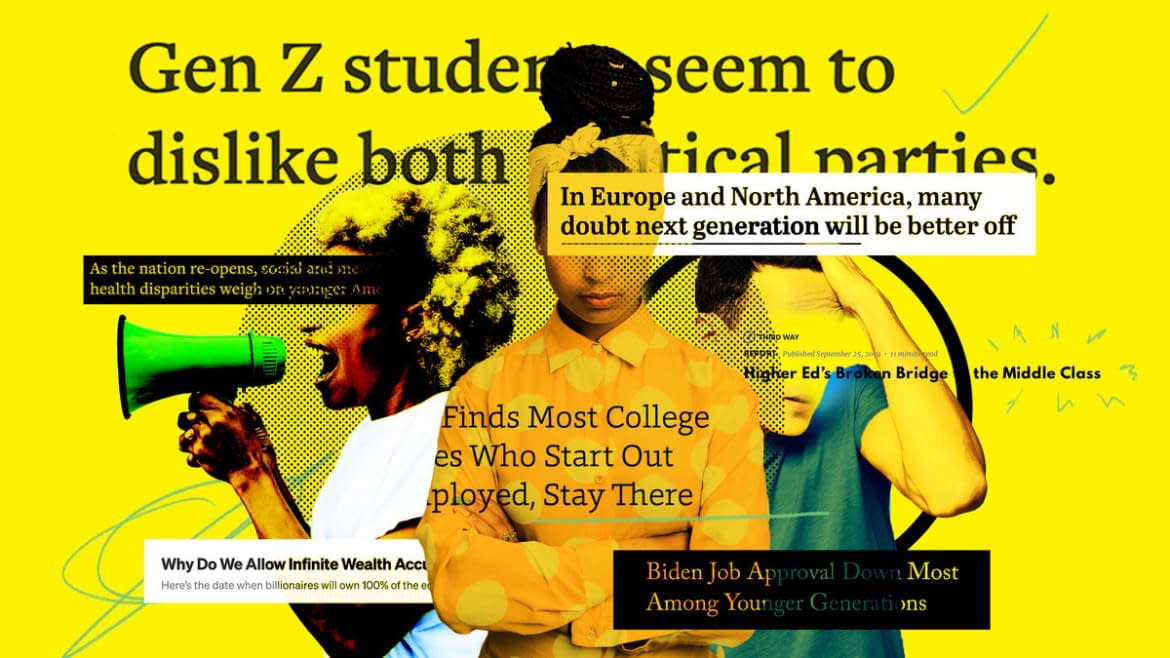

The Kids Are Not Alright and the Center Is No Longer Holding

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Across the West, the young are losing faith in the future.

The recent French election provides a case study. In the first round vote, voters narrowly favored President Emmanuel Macron, the epitome of “enlightened” elite rule, over Marine Le Pen, the doyenne of French fascism. While those two are now facing off, it was Jean-Luc Mélenchon, a grizzled former Trotskyite with a far-left agenda, who finished first among voters under 35, followed by Le Pen, while Macron was far back in the pack as the established parties of the left, center and right all collapsed.

Students at the Sorbonne, many of whom backed Mélenchon, are taking to the streets to protest the choice between far-right Le Pen and the elite technocrat Macron, who now seeks to win them over by declaring a net-zero emissions agenda, based in large part on nuclear power.

Much the same youthful alienation is evident here. Ahead of a likely rematch between what would be a 81-year-old Joe Biden and a 77-year-old Donald Trump, American politics seem geriatric and sclerotic. And the pandemic has only made things worse. Young workers were particularly vulnerable to job loss, as they were overrepresented in high-risk service sector industries, notes Pew. And now they are in the crosshairs of inflation, most notably for rents that are up 17 percent in major cities already this year.

Despite notions that younger voters would remain reliable Democrats,, Biden has already lost his majority among the young, the same troubled generation that helped elect him. Biden has seen his approval number among the twenty-something members of Generation Z plummet from 60 percent to 39 percent, notes Gallup. Among Millennials—those born between 1981 and 1996—he’s plunged from 60 percent to 41 percent. Other polls, including a new one from Quinnipiac, show the same dynamic.

The Coronavirus Means Millennials Are More Screwed Than Ever

Here, as in France, it turns out that young voters are not the sure thing many progressives had hoped. Pollster Sam Abrams has found that a small majority of students reject both political parties; only 18 percent think the Democrats are moving in the right direction which looks good only in comparison with the 10 percent who think that Republicans are doing so. Most young voters, according to the Pew Research Center, are neither liberal, outside of cultural issues, nor conservative. A strong majority think the country is headed in the wrong direction.

Why so alienated? Start with economics. In the United States, the odds of a middle-class earner moving up to the top rungs of the earnings ladder has dropped by approximately 20 percent since the early 1980s, meaning the young face diminished prospects. A Deloitte study projects that Millennials in the United States will hold barely 16 percent of the nation’s wealth in 2030, when they will be by far the largest adult generation. Gen Xers, the preceding generation, will hold 31 percent, while Boomers, entering their eighties and nineties, will control 45 percent of the nation’s wealth.

Not surprisingly, many young people—and not only in the United States— are deeply pessimistic about the future, and show levels of anxiety far more pronounced than other generations. In 2017, the Pew Research Center found that poll respondents in France, Britain, Spain, Italy and Germany were even more pessimistic about the next generation’s prospects than those in the United States. Such sentiments were also shared in countries like Japan and India, where many new college graduates fail to find decent employment.

There are two key issues alienating the young and creating a stark generational divide: the lack of high-paid steady work and the rising cost of housing. In previous decades, young people could, with confidence, assume that, particularly with a college education, they would be assured of decent employment. But a recent analysis of Federal Reserve data shows that young Americans with a college degree today earn about the same on average as their Boomer grandparents without degrees did at the same age.

Upwards of 40 percent of recent college graduates now work in jobs that don’t typically require a college degree at all. Indeed, a 2020 survey found that only a third of undergraduates believe their education has advanced their career goals, and barely one in five think a bachelor’s is worth the cost.

In 2018, half of all recent college grads made under $30,000 annually and as they age, many of these workers may never really enter the high-end job market. Your local Uber driver or Starbucks Barista is not likely to become tomorrow’s entrepreneurial success, nor will the part-time teacher of gender-studies work at anything but low wages. Indeed a recent study suggest that most underemployed graduates remain so permanently.

This certainly explains the appeal—here and in Europe—of neo-socialists like Mélenchon and Bernie Sanders who easily out-polled Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump combined among voters under 30. A poll conducted by the Communism Memorial Foundation in 2016 found that 44 percent of American Millennials favored socialism while 14 percent preferred fascism or communism. There are rising calls for the expropriation of wealth to fund a vastly expanded welfare state.

Expect those calls to be amplified by progressives—although not their gentry allies—ahead of the 2024 election, which will mark the point when as many Millennials and Zoomers are finally eligible to vote as the long dominant Boomers—and when Bernie Sanders, who would be 83, “would not rule out” another run if Biden does not seek reelection.

Young people, particularly the educated stuck in low-paid jobs, could propel a nascent rebellion among the expanding precariat of workers. Most of these workers are non-college educated and poorly paid, while living with uncertain hours and few benefits.

The recent Amazon vote in favor of a union in the company’s high pressure, tech-monitored warehouses could be a precursor. Other massive firms like Starbucks, Apple and Google are also under pressure; even in the media and tech fields there are growing organizing efforts.

Demographics could add to the Millennials’ leverage. Labor-force growth has declined with plummeting birth rates and reduced immigration. Over the past decade, new entrants to the labor force have dropped by 2 million, notes the consulting firm EMSI. Nearly 90 percent of companies surveyed by the U.S. Chamber of Commerce blamed a lack of available workers for slowing the economy, more than twice as many as blamed pandemic restrictions.

The other big generational dividing line is property. In 2014, French economist Thomas Piketty produced a widely referenced analysis of world inequality. Soon thereafter, Matthew Rognlie of Northwestern University found that virtually all of Piketty’s increased inequality was attributable to increased property values. In the United States over the past decade the proportion of real estate wealth held by middle-class and working owners fell substantially while that controlled by the wealthy grew from under 20 percent to over 28 percent. With property wealth now growing much more rapidly than income and interest rates rising, putting home ownership that much further out of reach for those who haven’t yet achieved it, the gap between the haves and the have-nots is, once again, growing dangerously wide.

In the meantime Wall Street has been gobbling up single-family homes, further raising their prices, with the goal of renting them, particularly to priced-out Millennials. This isn’t supporting renters but rather the rentier class—which Piketty calls the “enemy of democracy”—assuring them of steady profits by collecting rents while the middle class loses its independence as homeownership rates stagnate or decline, particularly among the young, in the United States, the U.K. and Australia.

Homeownership long has been a passage to stable neighborhoods and financial security. Homeowners have a median net worth more than 40 times that of renters, according to the Census Bureau. Pricing most Millennials and Zoomers out of homeownership will leave many, if not most, as property-less serfs, even if they hold decent jobs.

The shape of our future politics will be determined by these forces. The left can offer free college, universal health care and rent control to generations where few can afford to buy a home of their own. This program—offered by old left-wing warhorses like Sanders and Mélenchon—would likely appeal to both urban sophisticates and the vast service class of low-paid workers.

A growing labor shortage could, in the short run, reinvigorate the traditional—as opposed to the trendy—left, by helping empower workers to demand the sort of benefits that industrial workers, like those at car plants, enjoyed for decades.

It could also accelerate the end of Boomer-led globalization and support for mass immigration. Already, Le Pen in France and populist and nationalist parties in Sweden, Hungary, Spain, Poland, and Slovakia have done particularly well among younger voters. In fact, many of the right-wing nationalist parties, some with some racist elements, are led by Millennials and they appear, generally, on the rise in an inflation-rattled, increasingly pessimistic continent.

The trend here is toward a politics that pits the right-leaning young people in rural areas, exurbs, and small cities against a hard core of urban residents determined to go further to the left, with both groups defined by alienation and open to authoritarian tactics. Each will be angry not only at the system, but at each other. One may want to use power to shrink the state, at least in areas that don’t hurt their interests, while the other aims to expand it.

A better solution, suggests pollster Abrams, would be for parties to focus on the real needs of the next generation and deliver less ideology and more results. To capitalize on that opportunity, Republicans need to move away from social positions out of whack with the younger generation and from Donald Trump, who is highly unpopular among younger voters. Democrats, whose leadership tends to gerontocracy, need to add something other than virtue-signaling and repression if they want to keep the young onside.

This is more than a partisan issue, or one that’s unique to America. Whatever their politics and party, the older generation needs to address the sources of alienation and anger among the young, particularly if they value continuity of core institutions. A civilization that no longer provides the prospect of better times for its offspring cannot be long maintained, and certainly won’t thrive.

Get the Daily Beast's biggest scoops and scandals delivered right to your inbox. Sign up now.

Stay informed and gain unlimited access to the Daily Beast's unmatched reporting. Subscribe now.