The Kids Who Snitched on Their Families Because DARE Told Them To

When 11-year-old Crystal Grendell was called into the counselor’s office at her Searsport, Maine, elementary school in April 1991, she likely did not expect to be asked if her parents used drugs. After thinking it through—and likely following some pressure—Crystal reported that her parents smoked marijuana “once in a while.” The counselor, after pulling Crystal out of class multiple times over the next few days to inquire how she was doing, suggested Crystal go to the police station to tell Sgt. James Gillway, the school’s DARE officer, about her parents’ drug use. Crystal complied, but Gillway was too busy to see her.

The following day, Gillway, along with two other DARE officers, came to the school to interrogate Crystal about her parents’ drug habits. Playing on the trust that DARE officers had worked to facilitate with students through their role as teachers of the DARE curriculum—Crystal later recalled, “For an officer, I thought he was pretty cool”—Gillway told her that if she “cooperated” by informing him about her parents’ drug habits, there would be no consequences. Gillway, Crystal recalled, continued with a hardly veiled threat, telling Crystal that if she did not “cooperate” by snitching on her parents’ use of marijuana, both Crystal and her parents “would be ‘in a lot of trouble.’ ” Gillway concluded with a warning. He told Crystal not to tell her parents about their meeting because “often parents beat their children after the children talk to police.”

After Crystal complied, the officers pushed Crystal for information about her parents’ schedules and the layout of the house, and told her that police would go to her house to look for drugs. That afternoon, the police raided her home, arrested her parents, and took Crystal and her younger sister to a distant relative’s house—having neglected to make plans for the girls following the raid. The incident led to a civil suit against the officers. The court found in favor of Crystal, and the judge admonished the police, stating, “The officer’s coercive extraction of indicting information from an 11-year-old girl about her parents was shocking to the conscience and unworthy of constitutional protection.”

Most Americans have at least a passing awareness of the Drug Abuse Resistance Education (DARE) program. DARE is often ridiculed and parodied as a joke, and described as something that “didn’t work.” Oftentimes, people will laughingly remember smoking pot while wearing their DARE T-shirt. While these parodies are an important form of political critique, I found while researching my forthcoming book on the history of DARE that their lightheartedness obscures an important history of the DARE program that was much more insidious: The program turned unwitting kids like Crystal Grendell into the eyes and ears of the police.

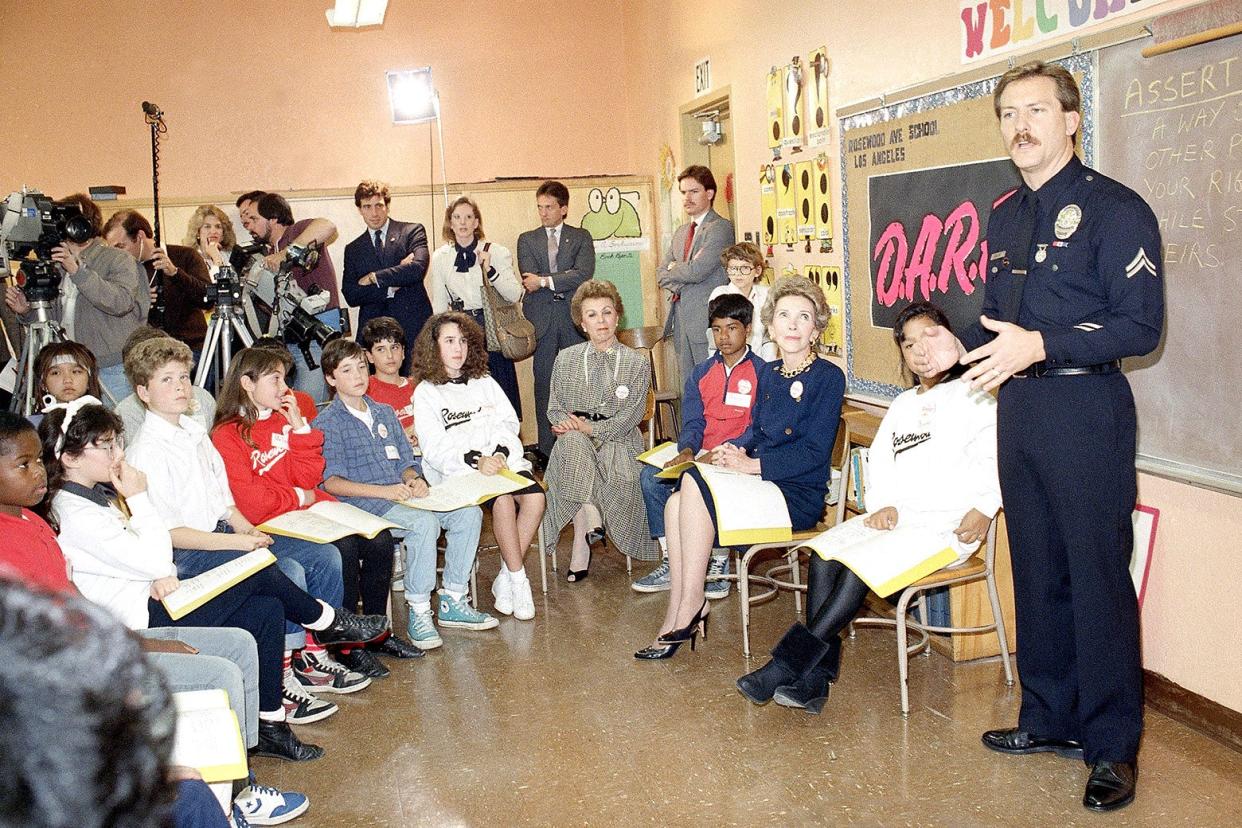

Police had long been involved with young people through Police Athletic Leagues, community relations programs, and Officer Friendly presentations. None of these programs integrated the police into the daily life of the schools through education as completely as DARE, with the accompanying goal—and potential consequences—of making the police officer a trusted friend and mentor to millions of kids nationwide.

What Los Angeles Police Department chief of police Daryl Gates envisioned when he proposed a drug prevention program for Los Angeles schools in 1983—the idea that would later become DARE—was a program that would turn children themselves into front-line soldiers in the war on drugs. It would do so by turning the police into teachers. But DARE officers never shed their primary role as police officers invested in a zero-tolerance approach to drugs.

The DARE curriculum suggested the DARE instructor was a trusted confidant who could be told when a student found drugs or knew of someone using drugs. The DARE curriculum emphasized the “Three R’s—’Recognize, Resist, and Report’ ”—as the primary lesson for students to take with them. Exercises in the DARE Officers’ Guide for Grades K–4 workbook from the mid-1990s, for instance, asked students to identify who they should tell if they found drugs. The possible answers included “Police” alongside “Mother or Father,” “Teacher,” and “Friend.”

Students were a quick study of DARE’s message. As one student wrote in their end-of-course DARE essay contest submission in 1994, “DARE means a lot to me. We practice as if we were in real situations. In this program we learn to give excuses and report if someone offers us drugs. We learned the three R’s. Recognize, Resist, and Report.” Students took the message and ran with it, not only reporting on those who offered them drugs, but also on family and friends who used drugs.

Federal officials reinforced the message that snitching on friends and family members was an act of compassion. The former secretary of education and the nation’s first drug czar, William Bennett, even encouraged children to turn in their friends for using drugs. “Let’s be absolutely clear about this point,” Bennett told students at W.R. Thomas Middle School in Miami in 1989. “It isn’t snitching or betrayal to tell an adult that a friend of yours is using drugs and needs some help. It’s an act of true loyalty—of true friendship. It’s the right thing to do.” Such encouragement meshed well with DARE’s “Three R’s” and contributed to a culture of surveillance among the nation’s youth.

Following the lessons taught by DARE officers in schools, students would occasionally tell officers about problems ranging from abuse to relatives who used drugs. As DARE administrators reported to the Office of Criminal Justice Planning, “Officers in the classroom have developed rapport with the students, which has resulted in students coming forth with information requiring intervention.” Indeed, Glenn Levant, former LAPD deputy chief and executive director of DARE America, the nonprofit organization that oversaw DARE operations across the country, related that students told DARE officers and school officials about parental cocaine use on a weekly basis.

And there was the notorious “DARE Question Box” placed in every classroom, which students could use to submit information, anonymously, to the DARE officer. While the Question Box was not advertised as a place for students to report on parental drug use, it often functioned in that capacity. As one aide to Wisconsin Rep. Gerald D. Kleczka observed in a 1996 briefing to prepare the congressman for a DARE graduation at Sacred Heart Elementary School in St.

Francis, Wisconsin: “In addition, they have a DARE box for kids who would like to give the officer a message but can’t or won’t talk about it in person. Officers have found that children will use this box to talk about physical or sexual abuse, or their parents’ (or their own) drug or alcohol abuse.” Providing children with a means to report abuse and violence may have been laudable, but the line between ensuring child safety and executing police surveillance was an especially blurry one.

DARE was turning kids into informants. While it’s unclear how widespread students turning in friends or family members for drug use became, anecdotal evidence from across the country highlights the insidious nature of using police officers as teachers who were meant to facilitate trust between kids and the police.

Law enforcement officials did not see much wrong with such practices. Sgt. Robert Gates, an administrative officer with DARE America, suggested to a reporter following Crystal Grendell’s case that arresting drug-using parents was a positive outcome. “In such environments, there are usually no morals, values, or training for the child,” Gates stated. “My personal opinion is that an arrest is the best thing that could ever happen to that parent. Marijuana could lead to harder drugs, which, in turn, could ultimately lead to death. What may turn out to be negative for the parent is positive for society.”

With the news of children reporting on their parents’ drug use to DARE officers, some parents began to speak out against DARE. While many parents supported DARE, others were more wary. In 1992, Gary Peterson, a parent in Fort Collins, Colorado, formed an organization called Parents Against DARE after his son brought home information about DARE. Parents Against DARE chapters grew quickly, spreading to at least 28 states in 1992. Many parents were wary of the use of police officers in schools and the enlisting of students as an adjunct to the police mission. “It’s a statewide police network run out of the attorney general’s office,” Ross Culverhouse, of a Minnesota Parents Against DARE chapter, asserted. “I don’t want the police or the school eliciting information about what’s happening in my house without my knowledge or my consent.” Summing up such parental opposition to using police officers as teachers, Peterson dubbed DARE “the stuff of Orwellian fiction. This is Big Brother putting spies in our homes.”

DARE America representatives did not see it that way. They were especially cutthroat when it came to suggestions that the organization turned kids into informants. DARE spokeswoman Roberta Silverman defended DARE from accusations that the program taught children to spy on their parents. When faced with stories of kids alerting their DARE officers to their parents’ drug use, she told reporters that “When students begin the DARE program they are specifically advised not [to] talk about their parents or friends. We are very clear that when DARE instructors are in the classroom, they are there as teachers, not as law enforcement officers.” However, in stating that “any time a child makes a disclosure [of parental drug use] to an officer, the DARE officer would be required like any other teacher to report that to the proper authorities or agencies,” Silverman revealed the ways DARE made schools into an extension of the police project.

Indeed, the lessons learned in DARE classes led to students telling DARE officers about parents or friends who used drugs more often than officials let on. In Caroline County, Maryland, for instance, a mother and father spent 30 days in jail after their daughter informed her DARE officer they had marijuana plants in their home. In Boston, two different students tipped off the police and walked out of their homes with their DARE diplomas in hand when the police arrived to apprehend their parents. In another instance, a student in Englewood, Colorado, called 911 when he found marijuana in a bookshelf at his home. The child proudly announced to the 911 operator, “I’m a DARE kid.”

Some students were dismayed by the consequences of their trust in the police. A 9-year-old in Douglasville, Georgia, for instance, told a reporter after informing on his parents’ drug use, “At school, they told us that if we ever see drugs, call 911 because people who use drugs need help … I thought the police would come get the drugs and tell them [his parents] that drugs are wrong. They never said they would arrest them. … But in court, I heard them tell the judge that I wanted my mom and dad arrested. That is a lie. I did not tell them that.” DARE’s effort to humanize police officers and make them into trusted friends and mentors enabled cops to become part of kids’ lives in ways that obscured the reality: DARE officers may have been teachers, but they were still cops at the end of the day.

Examples of DARE students turning in their own parents to the police for drug use continued to emerge on occasion and became national news, even as the DARE program receded in popularity, and in its use in schools, in the 2000s. As late as 2010, stories of kids turning in their parents continued to crop up. When an 11-year-old DARE student in North Carolina reported on his parents’ marijuana use that year—even bringing a joint into school as proof—following a DARE lesson, police arrested the kid’s parents and social services removed the child and his sibling from the home. “Even if it’s happening in their own home with their own parents, they understand that’s a dangerous situation because of what we’re teaching them,” the DARE officer concluded. “That’s what they’re told to do, to make us aware.”

Other evidence has come out about former DARE officers being sentenced for child pornography, prescription drug thefts, and sexually assaulting teenage boys. Along with the history of turning kids into the eyes and ears of the police, these stories suggest the dangers of police programs framed as a reform or a form of community policing. DARE was sold as a preventive program that would be divorced from the enforcement side of the drug war. But as the stories of DARE kids informing on their friends and family reveal, that separation was never as distinct as proponents hoped.

For Crystal Grendall, the message was clear. A year after the incident, Crystal told a reporter following up on the case, “I would never tell again. Never. Never.” She also reported that she “gets scared” seeing police drive by her house. The distrust and fear stayed with Crystal. As she told a reporter six years after her parents’ arrest, “It makes it hard for me to trust anybody. People I thought I could trust let me down.”