It was kill or be killed in the Korean War for this Latino soldier from Fort Worth

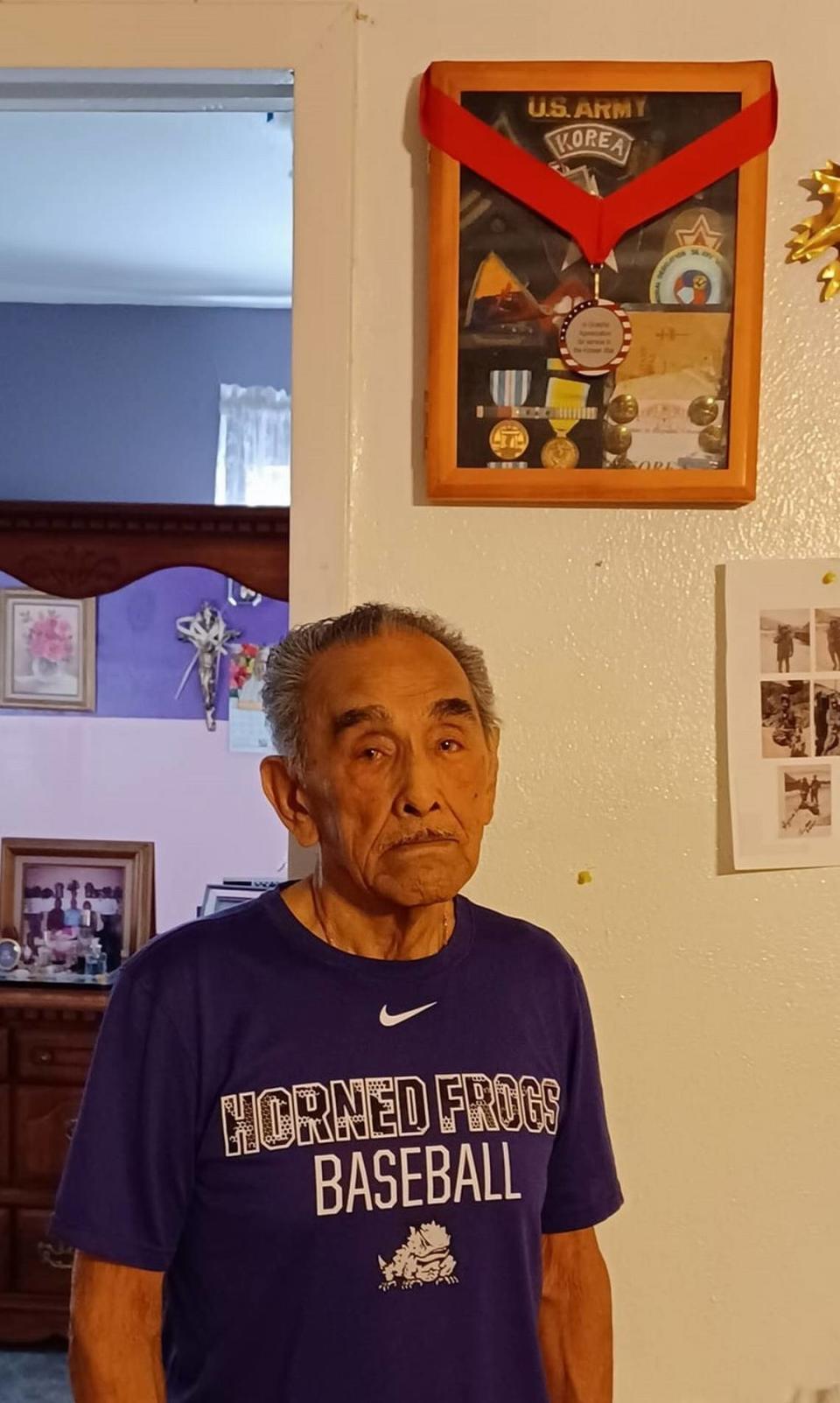

Although the Korean War (1950-1953) is often called the “Forgotten War,” Paul Vasquez, 91, remembers vividly his combat at the front.

On Christmas Day 1951, he and his Army unit exchanged gunfire from atop a hill with entrenched North Koreans on a nearby hill. The enemy’s rifle and machine gun fire raked the Americans’ position. The 5-foot-2 Vazquez took the vanguard with a Browning Automatic Rifle (BAR) mounted on a tripod while his comrades shot from behind during the four-hour firefight in sub-zero temperatures.

Vazquez recalled that before the war, he never imagined he could kill anyone. But in the heat of battle, bullets whizzing above, in front, and to his sides, he decided he or they would perish. A close look at his painting of the firefight shows a wounded American soldier. Two tanks that had transported the soldiers were both destroyed, killing the crews.

In letters to his Fort Worth family, he lied about his Korean experience, writing that his unit was training and in no real danger. The memory of a fallen soldier shot in the leg and calling for his mother and father before he died brought him to tears. The illustrated battle was one of many that Vasquez engaged in during his one-year Korean front combat.

Born Jan. 25, 1932, in Fort Worth’s Southside, he attended local schools until the seventh grade. Like many Latino men from impoverished households, he went to work at an early age with his father picking cotton in Britton, close to Mansfield. He was drafted at 18 and mobilized along with thousands of young men to repel the North Korean invasion of South Korea. According to Latino Advocates for Latino Education, 180,000 Latino soldiers, mostly Mexican and Mexican Americans, fought in the war.

The Pentagon tallied 54,246 American soldiers who died in the Korean War. According to the United States National Archives, Latino soldiers accounted for 3,734 deaths. Mexican American soldiers comprised 10 percent of the troops in Korea; however, they were less than 3.5 percent of the US population at the time. Of the 135 Congressional Medal of Honor recipients for valor in the Korean conflict, Latino men received 15 with 10 Mexican and Mexican-American awardees.

In 1942, the Mexican and United States governments signed an agreement, allowing Mexican nationals to enlist in the United States Army without losing their Mexican nationality. Mexicans joined the United States military during World War II and the Korean War. They hoped their service would result in their naturalization as US citizens at the end of their three-year military duty.

Enlistees included Mexicans who had entered the United States without legal documentation. Raúl Morin, author of “Among the Valiant,” said, “Even with the constant discrimination and continued denial of equal opportunities, when war came to the United States, no one could accuse us of draft dodging or fleeing to Mexico to avoid military service as charged in War World I.”

Richard Cavazos, born on Jan. 31, 1929, in Kingsville, heard the call to military service. After graduating from Texas Technological University (Texas Tech) and ROTC, he served as a first lieutenant in the 65th Infantry Regiment in the Korean hostilities. The regiment was called the Borinqueneers for their mostly Puerto Rican soldier makeup.

Cavazos distinguished himself by leading an attack and rescuing soldiers on Hill 142. For his heroic actions, he was awarded the Silver Star and Distinguished Service Cross. He later led an infantry battalion as a lieutenant colonel in the Vietnam War, earning his second Distinguished Service Cross. In 1982, he was promoted to four-star general, the Army’s first Latino person at that rank. On May 9, 2023, the Army formally changed Fort Hood’s name from a Confederate general to Fort Cavazos, a Mexican American military hero.

After Vasquez returned to Fort Worth and to his wife Betty Rosales, he suffered for several years from nightmares. He eventually stopped repeatedly recalling his unit’s attempt to bring food to dug-in GIs during the battle for Old Baldy. As he and his men returned to the supply depot, the enemy fired on them. He surmised the Chinese were toying with them since no one was shot. He also remembered the time his unit entered a South Korean-occupied village. They had decapitated a North Korean prisoner and displayed the head in a crate to villagers. An American captain confiscated the US soldiers’ cameras. Today, Vazquez has episodic but less intense war memory flashes.

He worked for an airplane parts manufacturer in Kennedale. When he approached his supervisor for a raise from the $1.35 an hour wage — never receiving an increase in his 25-year employment — he was told the company was losing money. He never recovered any retirement benefit withholdings from the business.

At first hesitant to apply for another job because of his limited education, he submitted his resume to General Dynamics. At the job interview, the hiring supervisor asked him to start the next day at $7 an hour. After 20 years at the F16 jet manufacturer, he retired at $30 an hour.

General Dynamics remembered to reward US combat veterans with honor, respect, and well-earned pay.

Author Richard J. Gonzales writes and speaks about Fort Worth, national and international Latino history.