Who killed the Robison family? 55-year-old mystery still haunts Northern Michigan

GOOD HART — Author Mardi Link speaks fondly of the safety and serenity in Northern Michigan.

“I think, in Michigan, we have this unique image of the words 'up north,’” she said. “Our state is so divided between woods and industrial areas that this idea of coming 'up north' is so idyllic.”

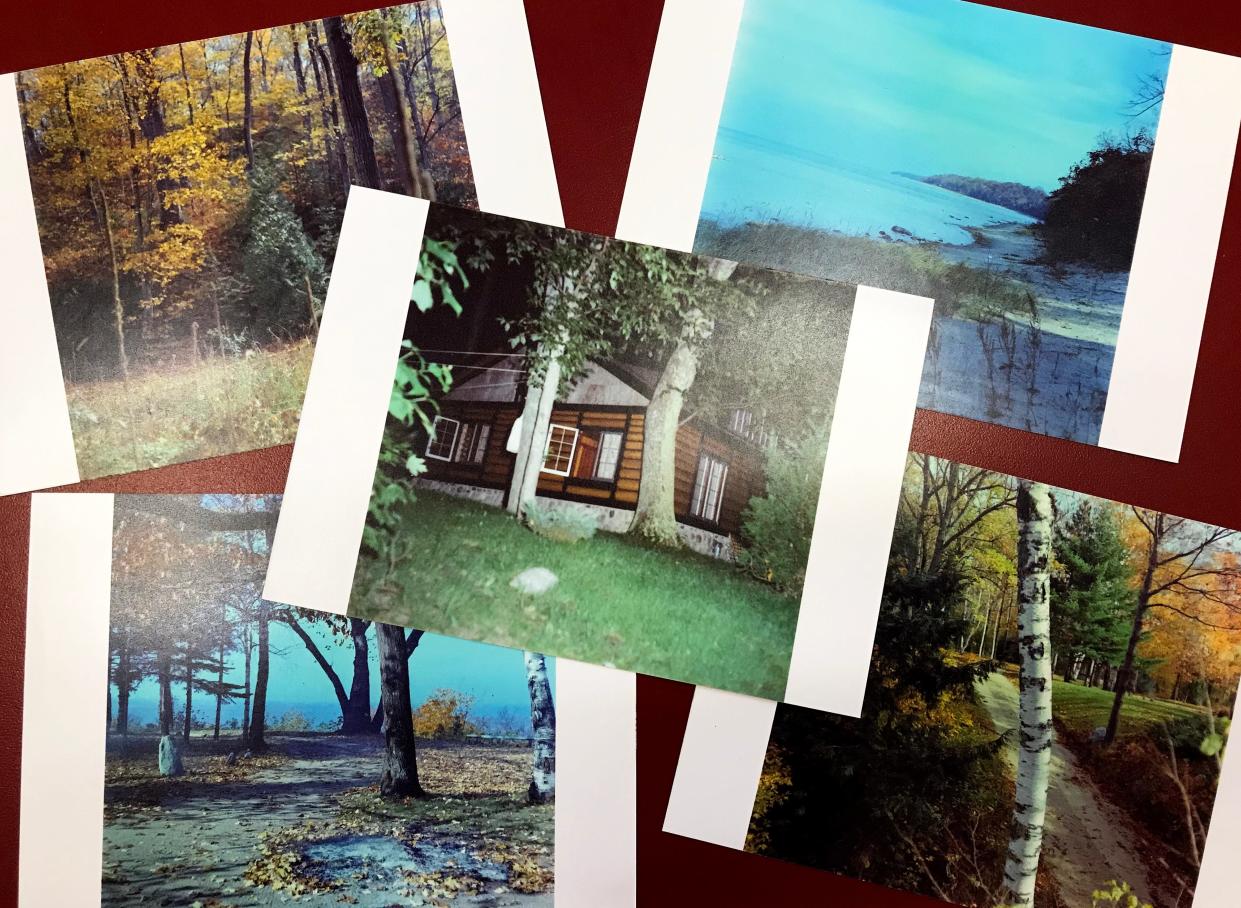

But that tranquility was shattered on a quiet night in June 1968, when an entire family was gunned down in their summer cottage along the shores of Lake Michigan near Good Hart.

More: Podcast: Revisiting the Good Hart Murders

More: Dickinson takes on area's most notorious unsolved crime in her new book 'Summerset'

“It was a terrible murder where a whole family was taken and it happened in a little sleepy village, in Good Hart, where things like that aren't supposed to happen,” said Emmet County Sheriff Pete Wallin. “Just a sleepy little place with a general store and a post office. Things like that aren’t supposed to happen, but they did.”

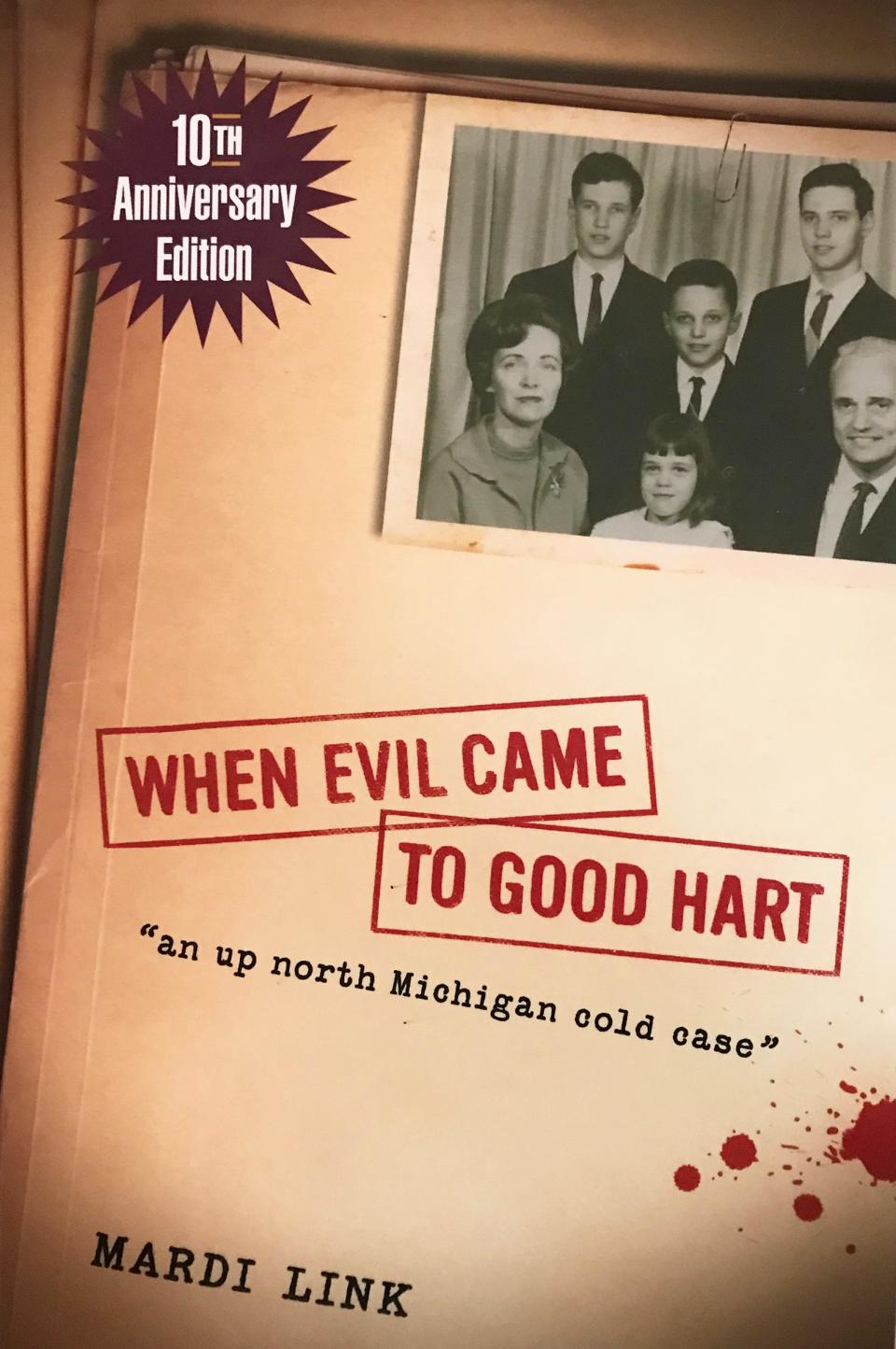

Link — who wrote about the case in her 2008 book: “When Evil Came to Good Hart" — heard about the murders, including all six members of the Robison family, as a little girl on the car radio. Her own family was driving north for vacation.

“A father, a mother, three sons, and one daughter. All dead,” Link wrote. “All killed with guns, the newsman said. There was more to the report: the girl, the daughter, the sister, was seven years old. The same age as me. My dad turned off the radio, and it grew quiet inside our car. How does a seven-year-old girl come to understand that evil exists in this world? How does a whole town come to understand it?”

The murders shook the small, tight-knit community and surrounding area. Neighbors reported fellow neighbors who'd been acting strangely. Law enforcement agencies investigated thousands of tips. And 55 years later, the case remains unsolved.

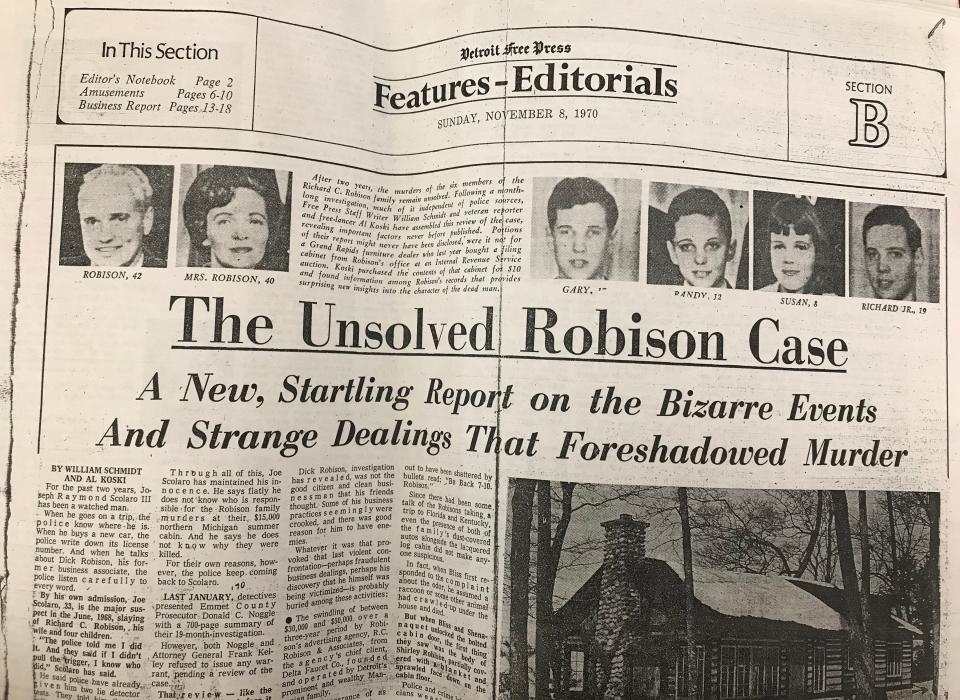

The Robison family — husband and wife Richard and Shirley; sons Richard Jr., Gary and Randall; and daughter Susan — traveled to their cottage in the resort community of Blisswood two miles north of Good Hart from their home in Lathrup Village in metro Detroit on June 16, 1968.

In the days before their deaths, the family was seen out and about. On June 24, they went shopping in downtown Petoskey. Later that day, Richard paid his respects to Chauncey and May Bliss, whose grandson, Norman, had been killed in a motorcycle accident the night before. Richard left $20 to buy flowers for the funeral.

Chauncey and his son, Monnie, had built many of the cottages in Blisswood themselves, including the Robison’s. Monnie worked as the caretaker for the cabins.

Richard told the Blisses his family was traveling to Kentucky and Florida the next day. Later, investigators learned Richard was hoping to view prospective real estate property.

It was one of the last times a member of the Robison family was seen alive.

Exactly when and how all six members of the family were killed remains unknown. Some facts from the following days and weeks are certain. Neighbors heard gunshots sometime during the evening of June 25. A note was found stuck to a cabin widow which read: “Be back by 7-10.” Two cars used by the family sat parked outside gathering dust. An overwhelming stench pervaded the area, and neighbors complained to the caretaker Monnie.

Monnie, who believed the smell was a dead animal, opened the cabin door and discovered the bodies on July 22.

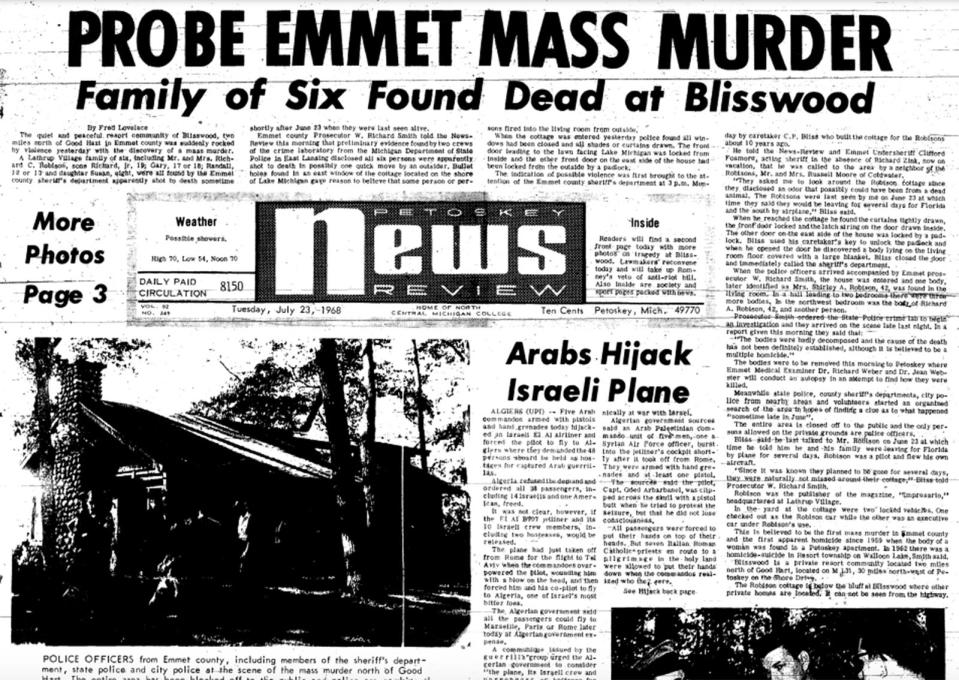

The July 23 edition of the Petoskey News-Review ran a big, bold headline announcing the "mass murder."

“When the cottage was entered yesterday, police found all windows had been closed and all shades or curtains drawn,” the article read. “The front door leading to the lawn facing Lake Michigan was locked from inside and the other front door on the east side of the house had been locked from the outside by a padlock.”

The article said the murder was "believed to be the first mass murder in Emmet County and the first apparent homicide since 1959.”

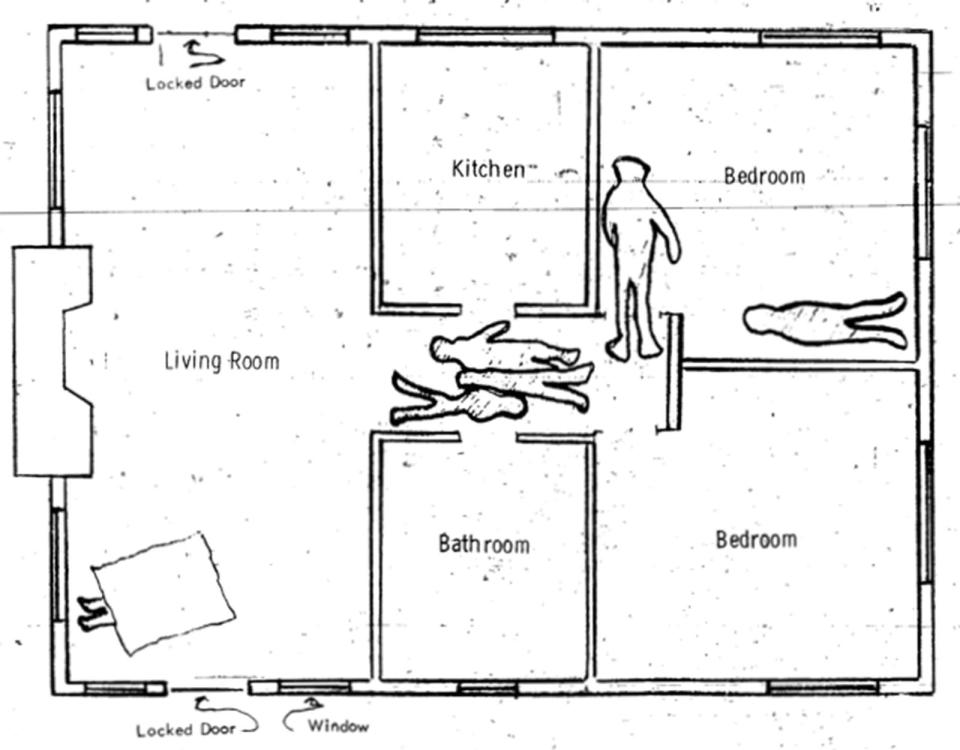

The Robison’s cozy cottage was a bloody crime scene. Shirley was found in the living room, partially covered by a blanket. Three more bodies — Richard, Randall and Susan — were piled in the hallway. Richard Jr. was found lying in the doorway from the hallway to a bedroom. Gary was sprawled in the same bedroom.

They'd all been shot, and the coroner determined Susan had also been struck with a blunt object. Officers found evidence from both a .22-caliber and a .25-caliber gun at the scene.

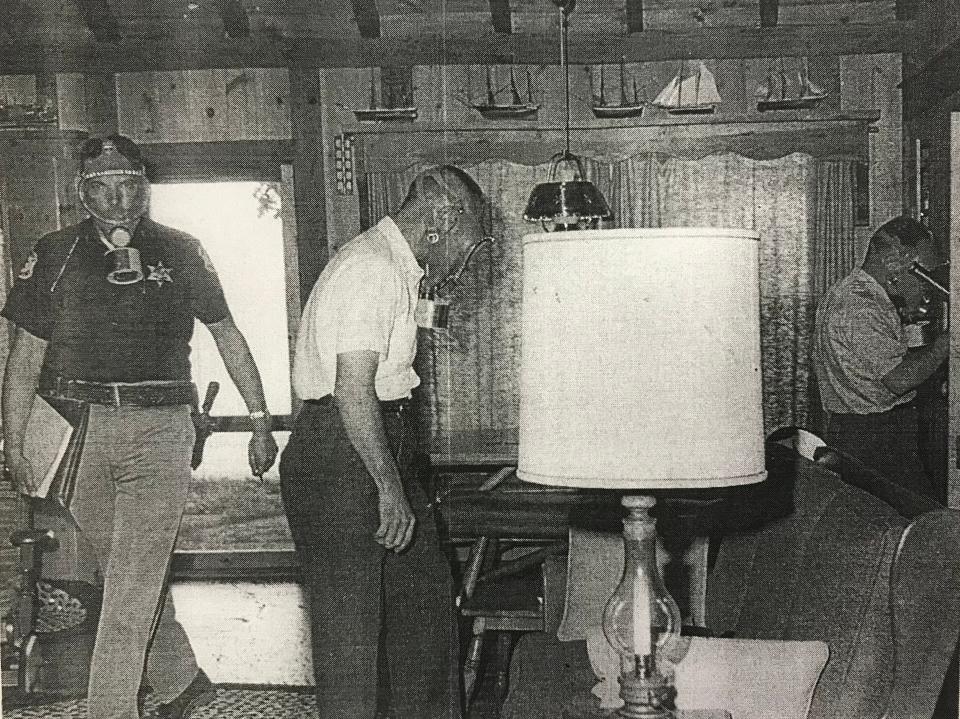

Because a month had passed between the time of death and when the bodies were found, first responders were faced with a gruesome scene. Thousands of dead flies littered the floor of the cabin. Some of the bodies had been left on a heating vent. In the original complaint file from the Emmet County Sheriff’s Office, dated 3:15 p.m. on July 22, one of the bodies is described as “in a very bad state of decomposition and mummification.”

Officers called for gas masks to investigate the scene “as the odor was almost unbearable.”

Emmet County Undersheriff Clifford Fosmore held up a bloody hammer outside and pointed out bullet holes in the side of the cabin as news reporters snapped photos and neighbors milled about.

Officers struggled from the get-go.

“Although the trail is as ‘cold as the winters in Northern Michigan,’ Emmet County Prosecutor Wayne Richard Smith and Undersheriff Clifford Fosmore are pressing their search for the killer or killers of the Robison family,” reported the Petoskey News-Review on July 25.

Investigators needed to identify suspects, and ideally find the murder weapons. They combed through the surrounding woods, fields and roadways in search of a gun that might have been discarded. Residents brought their own guns to the sheriff’s department to be tested.

“(Emmet County deputies searched), the state police did, and it’s never been found,” Wallin said.

In the meantime, investigators zeroed in on people of interest. One was Monnie, who died in 1980.

Wallin described Monnie as “a little different individual.”

“Monnie’s son, Norman, had been killed prior to the murders. Mr. Robison felt bad about it and went over to offer money for flowers, but you’ve got to remember Monnie Bliss was a little different individual,” Wallin said. “There’s theories that he was not happy with the gesture, so people think he did it, too. There’s so many theories out there.”

Officers interviewed drifters, prisoners at nearby Camp Pellston, and others.

In the July 25 edition of the News-Review, it’s noted that “Mr. Robison’s business associate Joe Scolaro flew to Petoskey from Detroit on Tuesday on a chartered airplane to talk with authorities. Scolaro assisted Robison in the publication of an art magazine called ‘Impresario.’ He told Fosmore he was particularly shocked by the murders since he and Robison were ‘more like brothers’ than business associates.”

In time, Scolaro became the prime suspect.

Scolaro had been left in charge of Robison’s advertising and publishing business while he was away. While once a close confidant of Richard’s, investigators uncovered evidence that Scolaro was embezzling.

His alibi for the day of the murders was filled with inconsistencies. He failed lie detector tests and, even more damning, he was known to have once owned .22-caliber and .25-caliber guns.

“There’s other things that point to him, too, but his alibi just couldn’t be confirmed,” Wallin said. “The question is, did he do it himself or did somebody help him? That’s the thing, because it’s hard to believe that a guy could kill all six people by himself.”

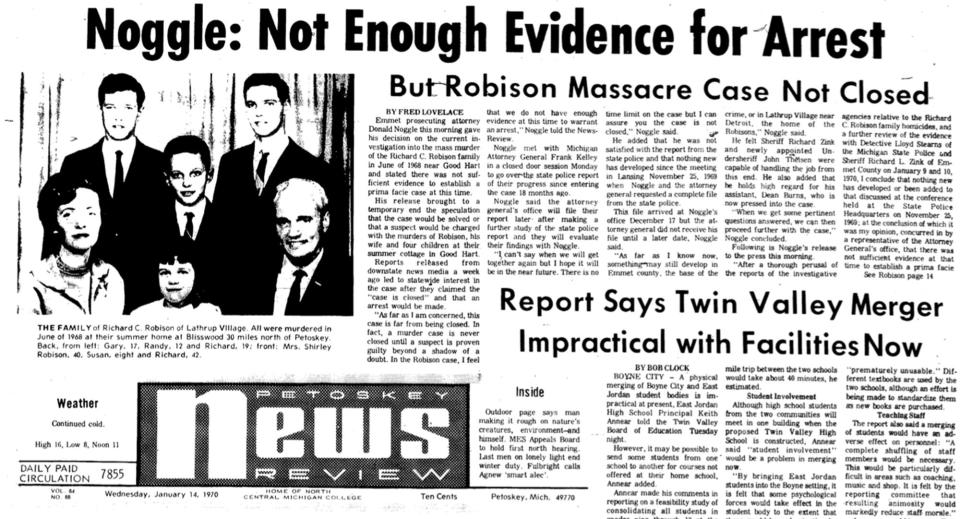

Michigan State Police investigators presented their case to Emmet County Prosecutor Donald Noggle in 1970, who declined to issue an arrest warrant.

“As far as I am concerned, this case is far from being closed,” Noggle told the News-Review in a Jan. 14, 1970 article. “In fact, a murder case is never closed until a suspect is proven guilty beyond a shadow of a doubt. In the Robison case, I feel that we do not have enough evidence at this time to warrant an arrest.”

But the case didn’t stop there. In 1973, Oakland County’s Prosecutor L. Brooks Patterson expressed interest in the case. He had reason to believe the crime had originated in Oakland County, and took steps towards re-evaluating an arrest warrant.

“Scolaro, I don’t how he caught wind of it that there were charges that were going to be coming against him for the murder of the Robisons,” Wallin said. “That’s when he committed suicide.”

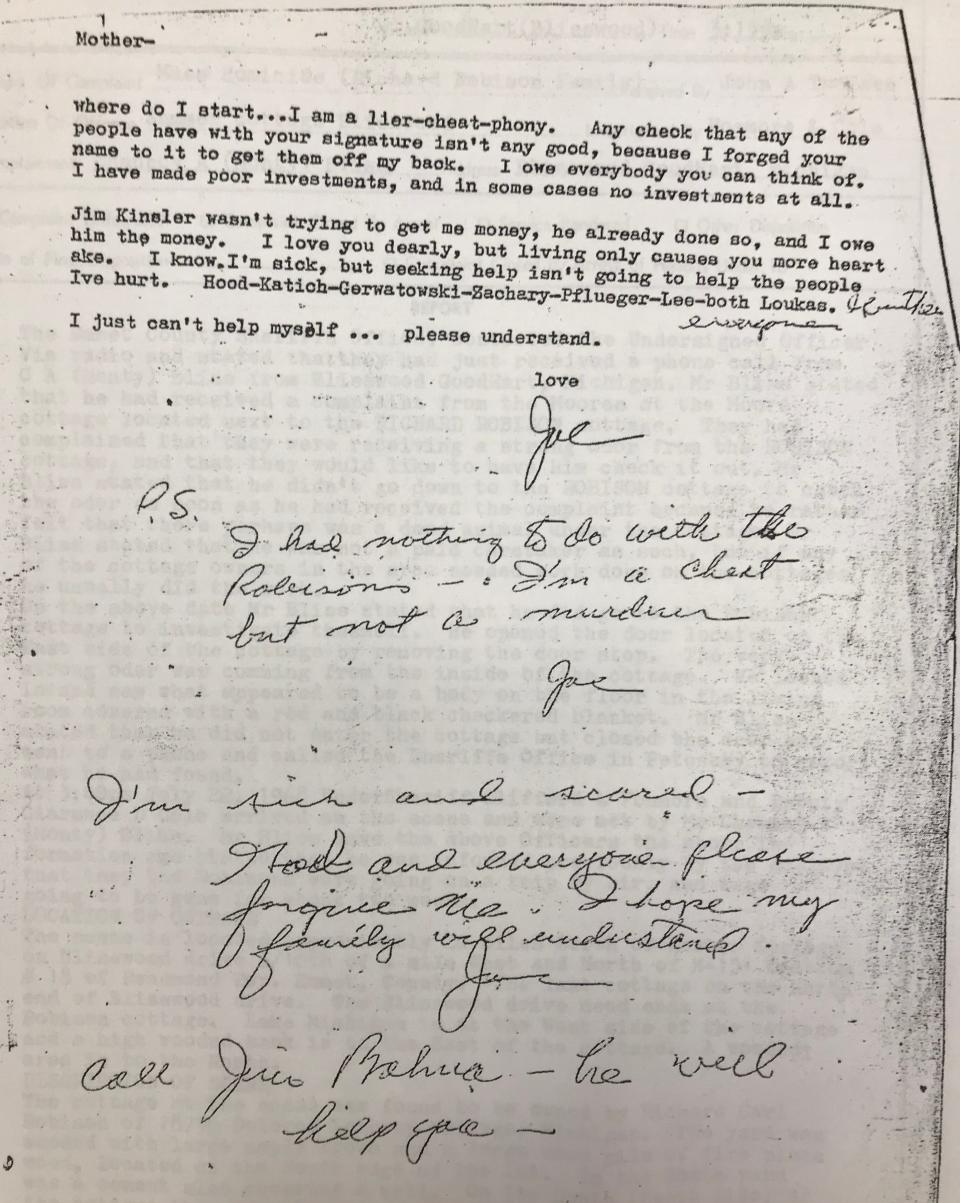

Scolaro killed himself on May 8, 1973. He left a note on his office door warning his mother not to come in. In another note, Scolaro called himself “a liar—cheat—phony,” but again denied having anything to do with the Robison’s deaths.

“I had nothing to do with the Robisons,” he wrote. “I’m a cheat but not a murderer. I’m sick and scared. God and everyone please forgive me. I hope my family will understand.”

With their prime suspect gone, the case stuttered to a standstill. It remains there today.

“It’s never been solved,” Wallin said. “There’s a lot of theories about how it happened, but it’s been 55 years and it hasn’t been solved yet. And probably, and I’m pretty darn sure, all the players are dead.”

Work has been done on the case intermittently over the years, but no significant progress has been made.

“We tried some DNA testing years ago with one of the hairs that was found on Mrs. Robison’s body but it was inconclusive,” Wallin said. “If we had the technology we have today, if we had that back in 1968, it’s pretty good that it would have been solved.”

Subscribe: Check out our offers and read the local news that matters to you

Every five years, when another notable anniversary passes and people are reminded of the case, Wallin said the sheriff’s department receives more tips. They investigate every single one.

“It’s an open case. It’s never been closed and it will never be closed until they determine exactly what happened,” he said. “When the (anniversary) stories run, we do get tips. We do follow up on all of them. Nothing has brought closure to it yet.”

Link said she hears from people interested in the case “all the time.”

“Usually they’re the same theories that I hear all the time: that Scolaro did it, or that Scolaro did it with help, or that it was the mob, or that it was a serial killer, or that it was Monnie Bliss,” she said. “Those are pretty much the range of theories that I’ve heard.”

The case continues to have a long lasting legacy in Northern Michigan.

“A screenwriter and I have finished a screenplay based on this crime that's currently making its way around Hollywood, so yes, I've definitely seen an interest,” Link said. “There’s always been an interest in this case in particular, but I think true crime is sort of having its moment and perhaps we as readers or as viewers when it comes to movies and TV want to understand why these awful crimes happen.”

But, while the case has been extensively documented over the years, Link said it’s important not to lose sight of the human tragedy at its center.

“I’ve gotten to know the surviving Robison family members and I see firsthand through them how this case has affected their lives,” she said. “When you kill a whole family, the people who are left are aunts and uncles and cousins. They’re going to forever wonder what happened to the people they loved. It’s impossible not to be moved and have an emotional reaction to that. I feel for their family, but also for people who were wrongly accused, like the Bliss family. I feel for them too.”

As it stands, both Link and Wallin doubt there'll ever be a definitive resolution to the Robison family murders.

“I think there’s still the possibility of a deathbed confession by someone who knows the outcome or knows who the guilty party is and has proof that we just are unaware of,” Link said. “So many people were interviewed for this case, so there could still be a deathbed confession and I think that, perhaps more than science, is our best hope for an open-and-shut conclusion.”

“It’s a mystery,” Wallin said. “A terrible murder mystery that these people were killed — the husband, the mother and the kids. It’s tragic.”

— Contact Jillian Fellows at jfellows@petoskeynews.com.

This article originally appeared on The Petoskey News-Review: Robison murders in Good Hart still haunt 55 years later