Killers of the Flower Moon Isn’t the First Movie to Tell This Story. Hollywood’s First Attempt Was Startlingly Different.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

If you’ve seen Killers of the Flower Moon, you know that it’s not the first time this story—the story of how, in the 1920s, William Hale and his nephew Ernest Burkhart amassed a fortune by murdering Osage landowners for their oil wealth—has been told. The movie ends with a re-creation of a 1932 episode of the radio show The Lucky Strike Hour, which, at the behest of the FBI, dramatized the murders and their investigation by the bureau, including scenes suggested by J. Edgar Hoover himself. Tom White, the real-life agent in charge of the case, tried writing his own account with the help of Osage writer Fred Grove, and although that version was never published, Grove evoked the killings in several of his novels, including 2002’s The Years of Fear. Several other novels were inspired by the crimes, and David Grann’s bestselling nonfiction book, the basis for the new movie, was published in 2017.

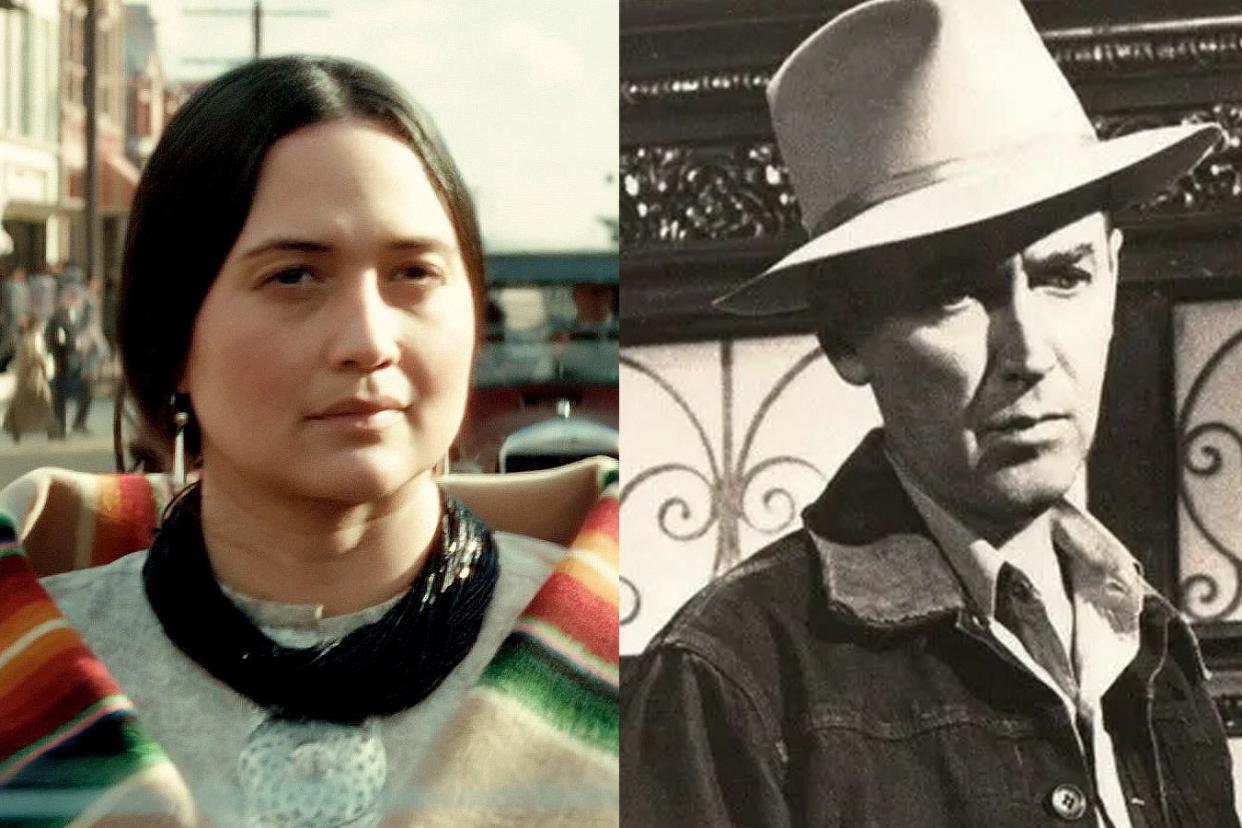

Martin Scorsese’s movie isn’t even the first time the Osage murders have been depicted on the big screen, but it is startlingly different from Hollywood’s previous attempt: 1959’s The FBI Story. (Native American director James Young Deer took on the case in 1926, but the film has long since been lost.) Based on the book by the Pulitzer-winning journalist Don Whitehead, the movie, which stars Jimmy Stewart as fictional agent Chip Hardesty, is about as close to literal copaganda as it’s possible to get. Hoover dispatched two agents to the set to monitor production and had director Mervyn LeRoy reshoot scenes when he wasn’t satisfied with the depiction of the bureau. Hoover even cameos as himself, as if to lend the production his personal seal of approval. While Stewart’s narrator makes a handful of disparaging comments about the state of the FBI during the three decades the movie’s episodic story spans, it’s only to illustrate how valiantly Hoover and his agents struggled against the inadequate resources of the bureau’s early years and, by implication, what productive use they’re making of the audience’s tax dollars in the present.

The Osage murders occupy about 20 minutes of The FBI Story’s two and a half hours, which places Stewart’s character in close proximity to several famous bureau victories, including the deaths of such colorful and notorious criminals as John Dillinger and Pretty Boy Floyd. The Osage Reign of Terror, as it is sometimes known, was just one not especially significant step on the road to the FBI coming into its own. At the time, Grann writes in Killers, “the Osage case was fading from memory,” and the movie shows little interest in any kind of fidelity to the historical record. Grann says that when White heard that the movie was incorporating his investigation, he reached out to Hoover and offered to make himself available to the screenwriters. Hoover apparently let that offer die with him.

Watching The FBI Story after Killers of the Flower Moon, a few familiar names stand out: Bill and Rita Smith, who were blown up in their home in 1923; Henry Roan, shot to death the month before that; and Roan’s cousin Mollie Kyle, the Osage woman who was married to Burkhart during the time of the murders. But other names are conspicuous by their absence. Perhaps because they were still living, William Hale and Ernest Burkhart are renamed Dwight McCutcheon and Albert Shaw. (Hale’s name survives, but only as the name of the invented Oklahoma county where the murders take place.) Stewart’s character takes Tom White’s place, although if White also had to deal with a nagging wife and a passel of overactive children while going undercover as a cattle salesman, Grann’s book does not record it. The FBI Story also invents the means of the Hale character’s capture, which here involves rooms full of dedicated specialists comparing the handwriting on different documents. In real life, the evidence included testimony from the doctor who cleared Roan for a life insurance policy that listed Hale as the beneficiary. The doctor recalled that when he asked Hale if he planned to “kill that Indian,” Hale laughed and answered, “Hell, yes.”

Killers of the Flower Moon restructures Grann’s book to place the focus on Ernest and Mollie, making White a supporting player. The FBI Story takes the opposite route, making Stewart’s character so central that all others are pushed to the periphery. There’s not a moment in its depiction of the murders that isn’t either witnessed by Chip or at least narrated by him. There’s more time devoted to his domestic squabbles than there is to any of the Osage murder victims, individually and possibly in total.

Although the Hollywood practice of using white actors in “redface” to portray Indigenous characters lasted into at least the 1970s, The FBI Story does employ Native American actors to portray its Osage characters, including Eddie Little Sky as Henry Roan and Dorothy Skyeagle as Rita Smith. But their characters are both figuratively and literally silenced. While the William Hale stand-in talks a blue streak, first posing as a concerned citizen before snarling at Chip once he realizes he’s been caught, the Osage characters don’t have a single line of dialogue between them. When a white huckster tries to sell Roan a life insurance policy on the street, Roan just looks at him blankly and drives off. We see him next as a corpse dangling from the passenger side door of his car on a remote country road, with, as Chip adds in voice-over, “only a coyote to blow ‘Taps.’ ”

Even more striking is the way The FBI Story treats Mollie. The wife of Dwight McCutcheon’s anxious nephew is mentioned a handful of times, but she never appears on screen. She’s not even a character, just a detail thrown in to give the story a little more color, the way Chip tells us what Bill and Rita Smith ate for dinner the night they were murdered. Instead, we’re introduced to the series of brutal murders by a depiction of the situation’s “silly side,” a collection of foolish fictionalized Osage too simple to handle their sudden influx of wealth. There’s one who buys three convertibles but doesn’t have the sense to put the tops up when it rains, another whose yard is littered with a dozen unused bathtubs, another who fills his house with telephones but has no one to call him. As far as The FBI Story is concerned, they’re little more than children, naïve and vulnerable rubes who could never have saved themselves without the help of the FBI—no matter the actual history.

The matter-of-fact way the Osage’s deaths are depicted in The FBI Story contrasts sharply with the later scene in which Chip’s partner is gunned down by a fleeing criminal. The partner gets a dramatic arc and a dying monologue, and his death further serves a dramatic purpose, illustrating the need for federal agents to carry firearms. The Osage are just bodies for the FBI to make a case out of. Toward the end of The FBI Story’s brief depiction of the case, Chip rages to his wife about the way the bureau has moved his family around the country. “The bureau has no right to send anybody down here with no churches and no schools and no decent food and no good doctors,” he yells, concluding by referring to his surroundings as “a hellhole like this.” The fact that the Osage will still be living in that hellhole long after he’s gone doesn’t seem to cross his mind.