A killing, then a cover-up? How three Florida prison guards got their stories straight

When Lake Correctional Institution inmate Christopher Howell, 51, suffered fatal injuries in his cell last year, slammed into a wall by corrections officer Michael Riley, it was yet another reminder of the institutionalized violence that festers in Florida’s prison system.

And as details of the incident emerge, another problem has been brought into sharp focus: How corrections officers back up each other’s stories when inmates are brutalized outside the view of surveillance cameras.

Soon after the incident, which left two walls of cell 2103 at Lake Correctional Institution smeared with Howell’s blood, Riley entered a room with then-Warden Amy Frizzell and watched what surveillance video was available from the incident. Then he and two coworkers filed use-of-force reports that would appear to at least minimize Riley’s criminal liability.

The three officers’ accounts of what happened at the critical moment match — nearly word for word.

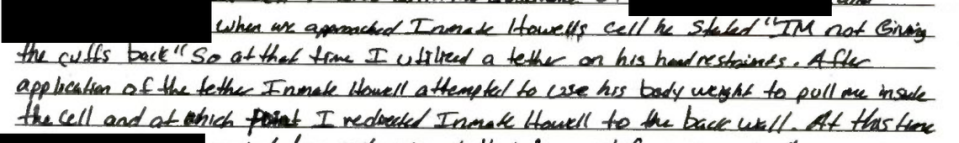

Riley, who is charged with second-degree murder: “Inmate Howell attempted to use his body weight to pull me inside the cell at which point I redirected Inmate Howell to the back wall.”

Fellow corrections officer Kevin Gonzalez-Delgado: “Inmate Howell attempted to use his body weight to pull Officer Riley inside the cell. At that point Officer Riley redirected inmate Howell to the back wall.”

Fellow officer Joseph Valentine: “Inmate Howell attempted to use his body weight to pull Officer Riley inside the cell and at that moment Officer Riley redirected Inmate Howell to the back wall.”

The resemblance is no coincidence. According to records of witness interviews conducted by the Florida Department of Law Enforcement and reviewed by the Miami Herald, Gonzalez admitted to FDLE investigators that both he and Valentine copied the text of Riley’s report rather than write their own. And Riley, who initially claimed to have shown the other officers his report “just to get the time,” also acknowledged that they all completed their reports together in Lake Correctional’s main front office.

Asked by FDLE investigators whether it is proper procedure for officers to write the same statement, Riley replied, “That’s just how it was, I guess.”

In fact, officers have been writing duplicate statements for years, according to former prison system inspector Aubrey Land. “All the use-of-force reports that are done — statewide — go to the [FDC Office of the Inspector General’s] use-of-force unit and all look the same,” and the unit doesn’t question it, he said. “They don’t require review of signatures and stuff like that. They just rubber stamp it and it goes right on through because it looks pretty.”

The coordination of stories can involve what everyone saw — or what they didn’t see. The Herald reported in 2015 how, during a cell extraction at Charlotte Correctional Institution, an officer jammed his index finger into an inmate’s eye socket and ripped out his eyeball, leaving it dangling down his cheek. When the use of force reports were filed, not one of the officers had seen anything.

Florida’s official use-of-force policy neither addresses duplicate reports nor forbids officers from completing reports together, but says that officers involved in an incident are required to submit reports that contain “a clear and comprehensive narrative of the circumstances that led to the use of force, the specific justification and necessity for the use of force, and a description of the actual events that occurred.”

The purpose of a use-of-force report is for officers to write down their independent knowledge of what happened, former warden at Florida State Prison and current prison consultant Ron McAndrew told the Herald. “To actually have [an officer] admit that he copied another person’s use of force is not an independent report,” McAndrew said. “It is a serious violation and should be regarded as such.”

But that principle is not spelled out in writing. The FDC policy says “if more than one officer was involved in the use of force, the initial officer using force shall complete the report.” Should another officer disagree with the details of that officer’s report, they should file an additional report, the policy says.

In essence, “it discourages officers from filing a report that contradicts or even has different facts than that first officer,” said Kelly Knapp, attorney at Southern Poverty Law Center, whose organization has sued the Department of Corrections for its treatment of inmates. “What a good policy would have is that every officer who was involved or witnessed the use of force would independently and separately be required to write their own report immediately after the incident.”

Under current policy, officers have up to 72 hours to file their reports.

The Florida Department of Corrections declined to comment on whether anyone else besides Riley — either the witnessing officers who wrote identical statements, the captain who signed off on the witness statements, or the warden who approved the statements — is under investigation or has faced any sort of sanction. Citing Florida Statute 112.533(2)(a), which states that information pertaining to a complaint filed against a correctional officer and the investigation of the complaint are exempt from Florida’s public records law until the investigation is concluded, FDC said, “we are unable to confirm or deny whether a sworn law enforcement officer is under investigation or has been reassigned.”

FDC’s Office of Inspector General does have an investigation related to Howell’s death open at this time, but FDC would not specify what the investigation is looking at. “The scope and nature of investigations are exempt,” it said.

The Herald was unsuccessful in reaching Valentine and Gonzalez. Riley declined to comment through his attorney.

“People would be right to question why officers can’t work off of their own memory and have to copy each other in remembering the events, especially with the culture of violence that exists with the Department of Corrections,” said Jackie Azis, an attorney at the American Civil Liberties Union of Florida and former criminal defense attorney. “There’s a history within the Department of Corrections of these types of deaths occurring, and an inability for a true and authentic explanation of what happened.”

Rep. Diane Hart, a Tampa Democrat who often advocates on behalf of inmates, was not at all surprised to hear of the duplicate reports.

“Since I got into this legislature in 2018, all of the reports that have gone out to investigate when people were beat up or killed, it’s just been lies and cover-up,” Hart said.

Though much of what happens in the prison system is captured by surveillance cameras, the use of force that led to Howell’s death was not. It occurred off camera, in his cell.

Cameras in the area nearby did capture the moments before Riley escorted him in, but the FDC never provides footage to news organizations, claiming, among other things, that release of the video would pose a security threat by revealing its surveillance techniques and the location of cameras. In reality, the cameras are visible to inmates and staff alike, and the blind spots — places beyond the cameras’ eye where inmates traditionally have been taken to be abused — are also well known.

Even so, according to the 80 pages of records reviewed by the Herald — which include summaries of video footage in addition to summaries of witness interviews with inmates, corrections officers and other Lake Correctional staff — some events preceding Howell’s death have been uncovered.

A routine matter

“Give me that tray,” an inmate overheard Riley say to Howell upon entering his cell last June, just days before his death. Howell was scheduled to get a meal for some inmates assigned to confinement known as a “loaf.” It is an unappetizing amalgam of different foods, squished together, often given as punishment. But there had been a mix-up. He got a regular food tray.

Once inside, Riley “snatched” the tray from Howell, one inmate said to investigators. Another, housed near Howell at the time, heard a sound come from inside the cell that he believed to have been a slap, so he submitted a formal complaint. Riley, however, did not file a use-of-force record of the incident as would have been required. Camera footage shows that he entered Howell’s cell that day and exited with a tray during meal service, according to FDLE’s investigative report.

At some point that day, Howell was also sprayed with a chemical agent while he was in the shower “to gain compliance,” Gonzalez said. The records obtained by the Herald do not reveal the officers involved, although officers must document when they use chemicals on inmates.

Four days later, Riley removed Howell from his cell and placed him in a separate shower cell so that Howell’s cell could be searched before an inmate was moved into the other bunk.

Handcuffed in the shower cell, Howell began to “yell unintelligibly,” FDLE investigators said. Riley removed the cuffs, speaking to Howell in words that “cannot be heard due to background noises,” they wrote. When he returned to Howell’s cell, footage shows that items were “tossed out” onto the floor.

Howell continued to make noises in the shower, eventually saying something that briefly caught Riley’s attention again. After the items from the cell were cleared, Riley handcuffed Howell behind his back and began to escort him back in.

Riley then pushed Howell through the cell threshold with both of his hands. The force was so hard, Howell “flew inside the cell,” an inmate recalled.

As Riley entered the cell behind Howell, Gonzalez and Valentine stood outside the door. Riley told investigators that, inside, Howell refused to have his handcuffs removed so Riley attached a security cord known as a “tether” onto Howell’s cuffs to prepare to remove them.

Though Riley and Gonzalez described the reason for the injuries Howell sustained in the moments that followed as the result of him pulling Riley into the cell by way of the tether, neither of the officers outside the cell intervened, FDLE investigators noted.

Valentine is seen on camera, leaning against the wall.

Within seconds, what had started as a routine matter ended with Howell unresponsive on the floor and two walls of his small cell stained with his blood.

In a grievance to then-warden Frizzell written that day, an inmate wrote: “Please pay attention — Today, June 18, 2020 I [witnessed] an officer commit a crime — Officer Riley assaulted an inmate [. . .] the inmate was under hand restraints — once inmate was inside his cell Officer Gonzalez tried to lock door but Officer Riley opened the door and violently assaulted inmate.”

“I am also in fear of my life and am asking for protection,” the inmate added.

Frizzell is no longer at Lake Correctional, having been transferred to Polk Correctional Institution in September. It was a routine reassignment, FDC said.

Orlando Regional Medical Center diagnosed Howell with a brain injury and fractures to his upper neck and ribs. He died the next day.

After examining Howell’s medical records and body for the autopsy, medical examiner Marie Hansen wrote: “It is my opinion that the death of Christopher Howell, a 51-year-old- white male, is the result of blunt trauma of the head and neck.”

“The manner is classified as homicide,” she concluded.

In their interviews, inmates said Riley had a “very, very bad temper” and was “always messing with people.” For two days, Riley had been telling Howell “I got something for you,” one said.

Hansen declined to comment, but former Palm Beach County medical examiner John Marraccini reviewed the autopsy report for the Herald. Since he was not able to view photos from the autopsy, he offered a preliminary opinion.

This type of injury sustained by Howell is caused by a lot of force, Marraccini said. The most common way he’s seen injuries like Howell’s is when “people are thrown headlong into a hard, unyielding object,” he said. Like being thrown into the side of a cruiser, or thrown down on an asphalt surface.

The arrest that ultimately led to Howell’s death took place in September 2018. He stole an $8 folding knife from a West Palm Beach Home Depot and four $15 portable phone chargers from a Target. According to a probable cause affidavit, when confronted by a store employee, Howell returned two of the chargers, but when asked for the others he said, “I have a knife, man,” and showed it, blade pointing out.

That got him a four-year sentence for, among other things, “aggravated assault with a deadly weapon.” Described in the arrest affidavit as “disabled” with a “juvenile disposition,” he was halfway through his sentence when he died.

Riley, who is free on $50,000 bond, was hired by FDC in March 2019 and proceeded to be involved in 22 use-of-force reports during a 10-month period before the incident with Howell. FDLE’s investigative records show he had been shifted to the prison’s confinement unit from the mental health unit both because of his “above average” number of use-of-force reports and because he himself requested reassignment.

He was discharged by FDC after his arrest in November.

Riley’s former coworker, Valentine, has been a corrections officer at multiple Florida prisons since 1998 and is still employed at Lake Correctional, as is Gonzalez, who has been an officer since 2018, when he was hired there.

Another potential avenue for investigation of Valentine’s and Gonzalez’s duplicate reports would be by FDLE’s Criminal Justice and Standards Commission, which oversees officer certification. However, whether the commission is investigating would not become public information unless it announces that it has found probable cause.

When the commission disciplines an officer, consequences can range from a letter of reprimand to decertification.

Valentine, Gonzalez — and Riley — are still certified.